Just Why

Alexandra Kleeman Brings The Apocalypse To Hollywood

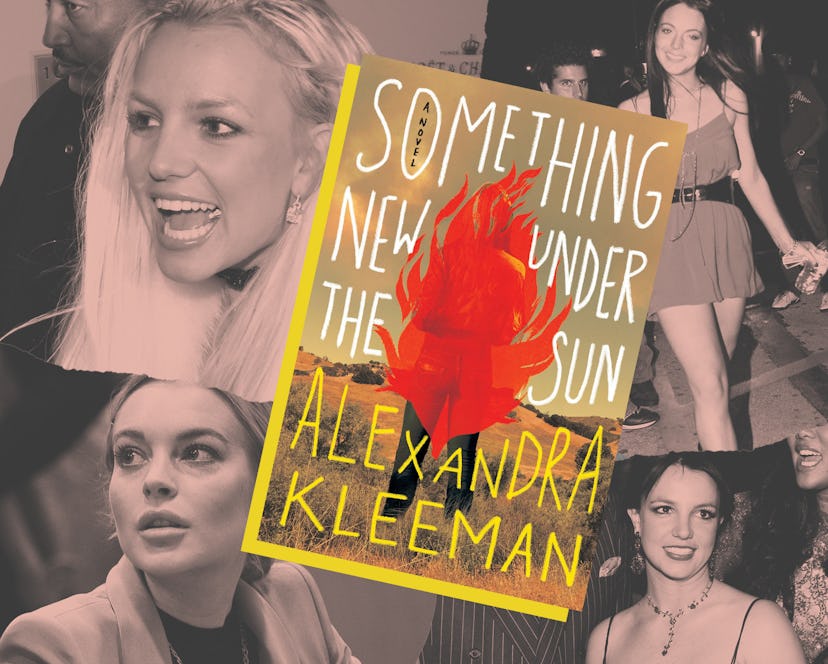

Part L.A. satire, part eco thriller, Something New Under the Sun asks how we exist in a world that’s burning down.

The new novel from acclaimed writer Alexandra Kleeman, Something New Under the Sun, begins with a familiar scene: a video, shared on a phone, in which a teen-star-turned adult train-wreck is having a meltdown. Kleeman’s teen star is Cassidy Carter, the onetime star of a plucky kid detective show who is now hustling for pay checks in B-minus movies, sketchy overseas sponsorship deals, and in licensing her appearance for copycat nose jobs. Sound familiar? It’s meant to.

“I grew up alongside Britney Spears’ and Lindsay Lohan’s ‘breakdowns,’” Kleeman tells me over the phone while traveling from the West Coast back east. “... It made me want to try to think about what it actually is to be the focal point of extraction in that way.” Kleeman turns a sympathetic eye on the deceptively smart Carter, who joins forces with Patrick Hamlin, a middling novelist who is delusional enough not to notice that his job as a PA is meaningless, but intrepid enough to (eventually) realize that the artificial WAT-R that’s replaced regular water in drought-ridden California might be trouble.

Part Hollywood satire, part eco thriller, Something New Under the Sun is tender and full-hearted but unambiguously bleak. Apocalypse licks at the corner of every page — besides droughts, there are wildfires and a mysterious, untreatable illness — but the book also rings an alarm bell for how we process fame and identity in 2021. I spoke with Kleeman about the inspiration for her story, her twilight hours writing process, and, of course, Britney Spears.

A big theme of Something New Under the Sun is the juxtaposition between real and artificial, and in that way, the entertainment industry feels like a perfect metaphor for a lot of what you’re trying to say. Did you know from the start that you wanted to tell a story centered on Hollywood?

Yeah. I also wanted to write a book that was set in Southern California because there are some similarities between Southern California and Colorado where [I grew up and] I’m most connected: the dryness and the drought. But I also think it’s amazing to look at the city as a place that’s at the epicenter of this sort of dreaming that we do so convincingly as humans. It’s a dream factory. Images are made that involve tremendous, tremendous amounts of labor and work and effort on every level from the writer’s room to production to post-production, and then it’s all folded into this image that looks effortless, like you’re just spying on it happening.

So, like the disappearance of that labor and creation of the dream is something that’s really fascinated me. It’s kind of a part of thinking that I’m in love with the most, and I also think it's sort of a scary and ominous thing how disconnected we can be from the reality that grounds those dreams, if that makes sense.

Have you had any personal experience with the strange quagmire of getting your work adapted for screen?

I actually adapted [my first novel] You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine, so I was actually working on that for a few years, and it was a really positive process. It was also interestingly different from writing a book on your own. When you write a book on your own, you can be this little god in this way you choose everything, you don’t have to justify it to anyone until a certain point, and if you don’t want to justify it at that point, you don’t have to do that either.

So, the way that decisions are scrutinized, the way that story is seen as this intensely, intensely plastic thing — like any part of it can change, any part of it can be better, and we’re always thinking about it in terms of something that can be pushed in one direction or another — that is a fascinating way to look at story.

Your book’s protagonist, Patrick — who somehow manages to be pretentious and naive at the same time — is one of the funniest characters I’ve read in a long time. Did any real-life writers inspire him?

[Laughs] I think Patrick is a little bit of a milkshake of different men who have appeared in my life, all sort of blended together. But also with a dollop of myself in there because I think I’m always surprised when I discover that I do sort of retain these areas of naivete around certain industries or things. I think as a writer, it’s easy to get jaded with the industry of publishing, but people are less so about filming and TV. It still seems like the place where fortunes can be upended completely and dramatic, television-worthy things happen to you. So, there’s some of that in there too.

I think Patrick is so enamored by this image of this place and the sort of possibility for success that he can’t see what’s happening to him clearly until the end of this book. You know, I also think, I’ve watched men for many years, and I think they are fascinating. Because — men can be very thoughtful but the pressure to self-scrutinize is lower in them, I think? They always contain a lot of things that are interesting in characters: these corners they can’t see around, these potholes that haven’t been noticed before that they can fall into suddenly. And that makes for a compelling character for me.

So much of the book is the tragedy and comedy of people distracting themselves or willfully ignoring the environmental catastrophes happening around them. Do you see that in the world today?

Yeah, I mean I think so because when we do have to pay attention to the apocalypse as we have for this summer and last summer and this past year, it prevents you from being grounded and absorbed in your own life that feels both realistic, pleasurable, and manageable. I think to incorporate into daily life the presence of a problem you can’t do anything about is very distressing, so I think it’s very natural for people to want to live in the narrower realm of life that is mostly grounded in things that they can make choices about. The larger question that I think about is there are larger actions that we can take as cities or towns or as a nation, and we need to begin seeing the problem and the personal on every level in order to start making this change. We’re in this problem now of scales that need to be collapsed. The scale that is individual needs to be reconciled somehow with the scale that is global, and I don’t know if we’ve ever been asked as a species to do quite this thing before, with such urgency.

The book offers a few possible answers, or at least responses, to the question of what we’re supposed to do when faced with the end of the world. One is through Patrick’s wife, Alison, who goes to a sort of retreat called Earthbridge. They’re not really taking action, but at least they’re acknowledging what’s happening. Are they supposed to have the right answer?

You know, I wrote this book with a sort of mourning feeling — it was during the Trump years and during the pandemic, and I didn’t feel like it was a book of solutions. But I think that there are different ways to live depicted in the book, some of which come a little bit closer with the situations that we see unfolding in the book. Alison lives in this compound where they’re acknowledging the environmental destruction that’s happening; they’re acknowledging loss; they’re coming together; they are creating a community that’s different from the community these people have lived in before. There is a voice at this commune, Nora — Alison and Patrick’s daughter — who’s sort of questioning whether leaving the situation behind really does anything to help it.

So, I think we’re seeing people move around the problem in the book and not decisively solve it. But in Nora, there’s some hope that someone who’s watching has a different vision and they will be able to enact it in the future. It’s a tension that always stays with me. You can be so worried about the natural world and the places that you’re personally attached to, and then when we go and spend time in them and find them kind of as you remember, it’s a soothing feeling, it’s an important spiritual feeling, and maybe it’s also soothing because it gives you the illusion that it’s permanent, still around, something durable there. Does that feeling help you return to your life and act with some greater agency to preserve it, or do we let that comfort just sort of soothe us for a while, and then we move on from it?

One thing I found strangely moving in your book was the way you wrote the character of Cassidy Carter. I think some people might be tempted to turn the “train-wreck actress” into a punching bag for comic relief or a stereotype of a bimbo, and instead she turns out to be one of the most intelligent and capable characters in the book.

I’m so glad you saw that in Cassidy because it was one of the main things that brought me to be interested in her. You know, I grew up alongside Britney Spears’ and Lindsay Lohan’s “breakdowns.” I was always the same age as Lindsay Lohan, and I felt that all of the media coverage was supposed to make me view her from this intensely distant scrutinizing perspective, but even though it was inaccessible, seeing her in a state of distress, what it made me want to try to think about what it actually is to be the focal point of extraction in that way that she and Britney were.

Britney gave the public everything they always wanted of her — she embodied this living fantasy, and yet they still wanted more! More access, more interiority, but not the actual interiority. I feel that these people were like canaries in the coal mine for us. We’ve become cognizant years later of how our emotional labor is extracted from us at work, how various things about our self-representation and outer-facing image are mandated from without but mandated to be generated from within.

I think seeing them aroused feelings in me about my own place within the machine that I've puzzled through for a long time afterward. It’s almost like they were the prequel to You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine.

Have you been following the news of Britney Spears and her conservatorship?

Yeah, I watched it all. And I’m so happy that it’s been on a positive swing recently. But there are still things she says that seem really smart to me and make me question my position spectating on it. When she was talking about how she appreciated the support from the documentaries but she doesn’t appreciate having these extremely humiliating and intense moments from her life re-circulate. To be drawn back again to the materiality of those videos, what they actually capture, whose body they actually show in distress, we’re not watching an idea of someone being pushed into this state by the industry. We’re watching someone’s actual body in a moment of intense vulnerability. And maybe even when we think we’re on her side, we have to re-humanize her while watching — or not watching, if that’s what she prefers.

Cassidy’s nose getting licensed and all these girls having the exact same nose is such a funny gag in the novel. I don’t know your relationship to social media, but have you noticed that between filters and certain cosmetic surgeries, there’s become a sort of ubiquitous “Instagram” face?

Totally, there totally is. This is a little off-topic, but I once had an idea for a science fiction story I was trying to write and it was all based around this augmented reality system that would allow you to basically do touchless plastic surgery by tweaking the way your face looks to everyone else through this common-consciousness-generating computing system. And I think like, through Instagram, we actually just got to that reality in a much quicker, cheaper, and more effective way! But there’s something about it that also has the potential for gentleness in it because it’s like maybe there’s an acknowledgment somewhere in the phenomenon of the Instagram face that it doesn’t really matter what your face looks like to yourself; it’s just an image you want to project to the outside world, and you can do that in a very low-effort way and then feel more satisfied with the untouched face that you have.

I don’t know. Have you ever looked at yourself with a filter and then removed the filter? Because for me, it’s like the quickest way of me feeling like my real face looks like a potato.

I feel like if we could actually do these things without actually investing in them at all, emotionally or psychologically, it would be fine! But that never happens; there’s always so much seepage between images of ourselves.

Transitioning to the opposite of social media: What’s your writing routine like?

I write really late at night, but this summer because I’ve been so busy, I’ve had a more normal schedule, which feels strange to me. Usually, I spend all day wandering around, dazed, trying to collect things that I’m going to use — reading, seeing if I find a rhythm — then after my husband goes to sleep, that’s when I sit down and I work until 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. or 5 a.m. or, if I have a deadline, until later.

I get no emails during that time; no one needs anything from me. No one can be contacted. It’s too late for any of that. It’s the most intensely peaceful time — it’s the only time I feel the absence of a clock, which is kind of what I need, given my anxiety, to feel free and like I’m not taking too long writing, and like I can explore and go in new directions. so that really is my time. Unfortunately, it makes the rest of my day feel like garbage.

What time do you wake up?

I wake up at like 11 a.m. or 12 p.m. maybe. So I’m also not sleeping very much on those days, and [it] usually goes fine for the first four days, and then five days in, I’m like, “I can’t do this anymore. I’m so confused.” And then I sleep a bunch for a couple days.

So are you drinking a lot of coffee?

I’m a coffee drinker, but I actually don’t drink that much at night. My parents have all of these stories about me staying up all through the night when I was a kid. I actually — this seems really strange to me the more that I think about it — remember five days, when I was about 8, when I was just awake. After my mom went to sleep and I couldn’t get to sleep, I’d get up and watch the really weird middle-of-the-night TV into the pretty weird morning TV. Like 3 a.m. TV into 5 a.m. TV. And I wasn't enjoying it; I wasn't entertained. I just had so much time all of a sudden because I couldn’t go to sleep.

There’s something that happens late at night where my alertness just focuses and I feel, like, I describe it as everyone else’'s awake-ness falls on me at once. Because they’re not using it; they’re all sleeping.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on