Books

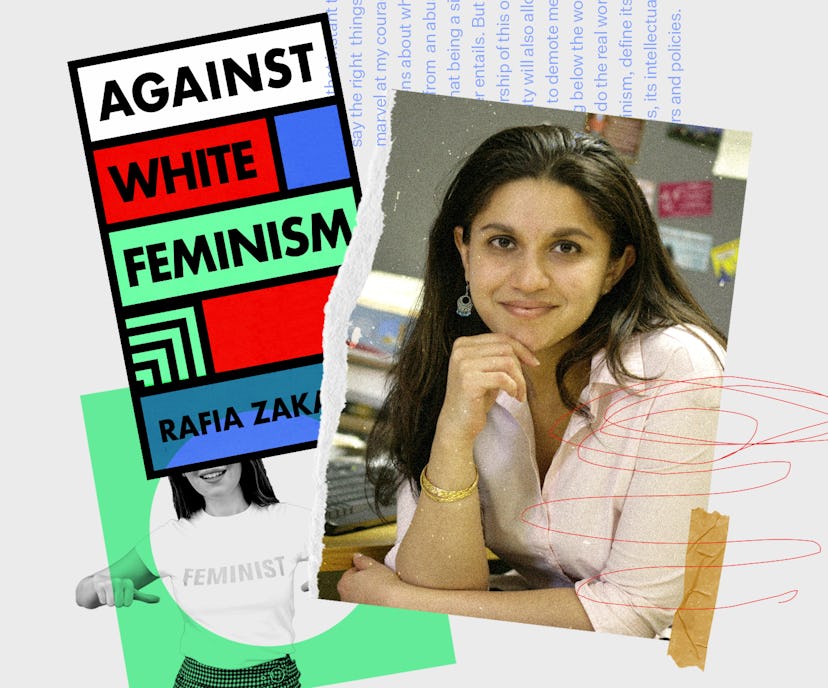

Rafia Zakaria Wants To Change The Way You Think About Feminism

“There is a division between the women who write and speak feminism and the women who live it.”

Rafia Zakaria’s “steady drumbeat of change to redefining feminism” is going to “light fires everywhere,” according to Literary Hub, which named the author’s latest release one of the most anticipated books of 2021. With Against White Feminism, Zakaria draws from her own experience to outline what exactly white feminism means, while also providing an empowering case for change.

Speaking to the Guardian, Zakaria recalled how white women have “obstructed” her in “every possible way” throughout her professional life. “Women like me never really make it,” she says. It is precisely these kinds of experiences are what inspired one of the central themes of Zakaria’s book: that modern feminism is catered to white, middle class, cis-gendered, Western women, and has been corrupted with links to white supremacy ever since the movement’s inception. To inspire radical change, it is important to first reflect on the past to gain a full understanding of how mainstream feminism continues to exclude people of colour from the conversation. Zakaria’s Against White Feminism thus proves the optimal place to start.

BBC broadcaster Mishal Husain says the author and activist’s latest work will “make you stop and think.” Co-founder of the Women’s Equality Party, Catherine Mayer, echos Husain’s comments, lauding Against White Feminism as “essential reading” for “anyone white who identifies as a feminist.”

In this excerpt, Zakaria sets the scene as a Sex and the City meeting “at a wine bar, a group of feminists ...” Well-heeled white women gathered for a drink in New York. As the only brown woman at the table, Zakaria considers her answers to their questions (some innocent, some less so) in an attempt to minimise the pity and discomfort that comes with sharing her story in such an arena.

Excerpt from Against White Feminism by Rafia Zakaria

An aversion to acknowledging lived trauma permeates white feminism, which in turn produces a discomfort towards and an alienation from women who have experienced it. I’ve sensed it every time I have found myself in such a conversation, but have only recently been able to recognise its connection to unexplored assumptions of the value of the voices that have experienced trauma.

By and large, there is a division within feminism that is not spoken of but that has remained seething beneath the surface for years. It is the division between the women who write and speak feminism and the women who live it; the women who have a voice versus the women who have experience; the ones who make the theories and policies, and the ones who bear scars and sutures from the fight. While this dichotomy does not always trace racial divides, it is true that, by and large, the women who are paid to write about feminism, lead feminist organisations and make feminist policy in the Western world are white and middle-class. These are our pundits, our ‘experts’, who know or at least claim to know what feminism means and how it works. On the other side are Black and Brown women, working class women, immigrants, minorities, indigenous women, trans women and shelter-dwellers, many of whom live feminist lives but rarely get to speak or write about them. In the rudimentary sense there is an assumption that the really strong women – the ‘real’ feminists, reared by other white feminists – do not end up in abusive situations.

In reality they do. But their disproportionate access to such as money, job security and established social networks means that they end up in shelters or in need of public resources such as Medicaid, food stamps and subsidised housing far less frequently than women of colour in the same position do. Conversely, women of colour – who are more often likely to be immigrant and poor – do have to take help from strangers and the state; they are the visibly needy and the obviously victimised. This imbalance is one of the factors that fosters and maintains women of colour as a passive source of cautionary tales. White women need help too, and they seek it as well, but the cultural attitudes that paint people of colour as freeloaders use any instances of women of colour seeking help as a means to confirm that prejudice.

There is also the powerful – sometimes voiced and sometimes implicit – assumption that non-white women suffering trauma is the ‘usual’ state of affairs, because their victimhood stems from their unfeminist cultures; while abused white women are portrayed as an aberration, a glitch, and not a reflection of wider trends or values in white culture. This is a prime example of the double standard by which whiteness, and the feminism that has sprung from it, asserts itself as inherently superior.

This phenomenon strongly discourages women like me from owning up to the hardships we have endured, thus further reinforcing the loop of assumption and seeming supporting evidence around what a feminist looks like: educated, successful, feminist women do not come from backgrounds of abuse, exploitation or trauma, and therefore women who have experienced these things are not credible feminists. The threat of being perceived as substantiating a discriminatory cultural norm – that of the abused woman of colour (and in my case, the immigrant and abused woman of colour) – enforces its own silence.

Against White Feminism by Rafia Zakaria is published by Hamish Hamilton and out now.

This article was originally published on