Entertainment

'Jurassic World' Takes A Critical Eye To Cinema

As far as subtextual agendas go in the case of today’s film slate, the anti-cynicism campaign is about as polarizing as the “Don’t club baby seals!” movement. After what the past few major studio releases — most recent of which being Jurassic World — would have you believe was a generation’s worth of artistic temperament hating on hopes and dreams of any kind, we’re seeing this chapter of cinema turn into a rally cry for the life-affirming wonder of Steven Spielberg’s orchestra-backed reveal of that first brontosaurus.

Agreeable though their point may be, those on its bandwagon haven’t actually been the most favorable spokespersons (spokesmovies?) available. As Tomorrowland laments the dispiriting character of action cinema, it contends with the exponentially more flavorful Mad Max: Fury Road. While Birdman sought an honest and original story to tell through the haze of blockbuster hegemony, it might have found one in its Best Picture competitor Boyhood. And Jurassic World is the most interesting failure of the lot, seeming to condemn not only movies in its class, but itself in particular.

Jurassic World is not off base in its assumption. Automatic audience surrogate Chris Pratt, first seen basking in the embrace of a glorifying sunbeam, stands cemented on the soapbox on behalf of the Hollywood magic “we” — that is, those old enough to have been affected by Jurassic Park the first time around — so desperately want.

He balks at theme park cog Bryce Dallas Howard’s (a thinly veiled take on the studio stooge) lobby for genetic enhancement (CGI) as nobody could possibly care about old-fashioned (practical) dinosaurs anymore. Complementarily, Pratt hates on his psychologically askew colleague Vincent D’Onofrio for visions of a new wave of militant raptors; the character speaks longingly for an era where dinosaurs are trained to kill for the good of man… in other words, for the good of the American box office.

But though Jurassic World sets up Pratt’s ostensibly Spielberg-friendly worldview as a philosophy of heroism, Pratt and the movie give way to everything valued by their oppositional ideologies.

Yes, Howard ultimately submits to nostalgia over new, calling in the big guns of franchise legend to do away with the monster she and myopic park owner/ivory tower studio head (though he’s kind of a spirited sort, admittedly) created in the first place. We even see the present demographic — Howard’s two nephews, embodying information-addled youngsters and pathologically unimpressible teens — give in to the glories of old, diverting faith from the Jimmy Fallon-endorsed gyrosphere to a make of jeep that should look especially familiar.

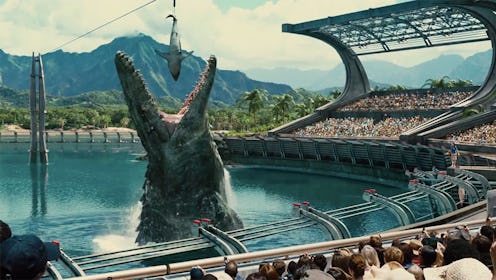

However, in company with Pratt’s eventual acquiescence to D’Onofrio’s raptor militia, triggered by an “any means necessary” mentality, we might have trouble identifying exactly what side Jurassic World is on. Is it pro-whimsy? Anti-nostalgia? On board with the contemporary wave of CGI and violence? Despite its propagation thereof, it certainly doesn’t seem to be. The movie lays hints throughout about the demolition of the Spielberg method, employing visual references to Jaws, via the instantaneous consumption of a shark by a ravenous computer-generated beast; E.T., whose likeness is reproduced in the face of a dying herbivore; and Spielberg's retroactive erasures of his own cinematic "cynicism," in a shot of laser-guided snipers in the park that bears striking resemblance to the E.T. sequence that Spielberg himself reformatted to replace police guns with flashlights.

The biggest clue that Jurassic World considers its own submission to the whims of the current era a failure comes with the final shot of in-universe fanboy Jake Johnson, one of the park’s mission control operators. Draped in old world swag, and armed with a collection of lo-fi dino figurines, Johnson glares lifelessly at the events of the world through his own feature screen, heaving a defeated sigh as the adventure comes to a close. It isn’t a sigh of relief over the spared lives of his colleague and her young nephews; it’s one of mourning. The world he thought he might have seen again has proven itself an impossibility. We can’t have that old Jurassic Park magic, as far as Jurassic World is concerned.

So what do we get instead? Everything we claim to hate. The CGI, the violence, the soulless references. These are the pieces that make up Jurassic World, a movie that nothing but bad things to say about all of them but concedes to the notion that we can’t possibly do any better. For an alleged member of the anti-cynicism campaign, that’s a pretty cynical way of looking at things.

Images: Universal Pictures (4)