Life

Facing My Family History And The BRCA Gene

I made the decision to get tested for the BRCA gene mutations because I am a person who needs to know all the information. I don't admonish people for posting movie or TV spoilers on the Internet — in fact, I often seek them out, because I hate surprises, and nothing bothers me more than knowing something might happen, but not knowing exactly what. As I've gotten older, I've gotten less rigid with this need for information; I accept that I can't control everything, but I've also learned that it's important for my sanity to stay on top of things — which is part of the reason it was so important for me to get tested.

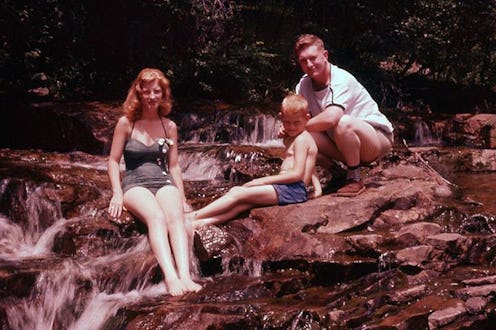

Another reason was my family history of cancer. Various forms run rampant on my father's side: lung cancer, skin cancer, prostate cancer, and yes, breast cancer. Well-intentioned warnings about always wearing sunscreen always came backed with a tinge of anxiety.

For me, the thumping of this anxiety has always been present, but echoed at a fairly low volume for most of my life. During my childhood and teenage years, I had more pressing things to worry about than the potential cause of my own future demise. Or perhaps I assumed that, by the time something toxic developed in my own body, science would have figured out a way to beat cancer for good.

But when my Aunt Carol was diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer in 2003, the volume of that internal thought-loop began to increase. The anxiety her diagnosis triggered in me (and, as I now know, my dad as well) had a clear voice: it said, "You are going to get cancer someday."

I was 16 when the cancer metastasized to her brain, almost exactly a year after her initial diagnosis. She passed away shortly thereafter. Rather than working through my feelings about her death, I pushed them to the side and avoided any sort of emotional conversation with my family. I did not express my personal fears about cancer, nor did I express empathy for my family members over the shared experience of watching a loved one in pain. I thought that by ignoring what had happened, the feelings created by the situation would disappear as well.

As I entered early adulthood, there was not much conversation in my family surrounding health concerns, cancer or otherwise. Other voices took up residence in my head: voices asking whether I could buy a new pair of boots and still make rent, how much homework I could skip and still earn a passing grade, how late I could stay out on any given night and still look semi-rested at work in the morning.

Then, one Sunday morning in 2010, my parents requested a Facetime session. I was living in Portland, far away from their California home, so it was as close to a face-to-face conversation as we could get. They told me that my dad had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and my whole body tensed. I felt the immediate physical manifestation of anxiety—a feeling like tiny pinpricks all over my body—and the original voice returned: “You are going to get cancer someday.”

I was fairly unhappy in Portland and had been considering moving home already. This was a clear sign that it was time. I came back to California as Dad started proton therapy treatment at Loma Linda Hospital—the best prostate cancer treatment facility that currently exists, we were told. Our proximity to such stellar medical care combined with the fact that they’d caught his cancer before exhibition of symptoms created what they call a “best-case scenario.” Terms like these are meant to inspire optimism and hope, and for me, my mom, and my brother, it mostly worked.

Though Dad felt slightly fatigued throughout the proton therapy, he still went to work every day. After the nine weeks of treatment, we were told that we had to wait six months before he could be tested to gauge its efficacy. The effects of the radiation had to settle in his body before they could get an accurate reading of his PSA levels. Even though I’m a person who hates surprises (as well as waiting for answers), I thought the worst was over. I was sure that the treatment had worked and that the results would be positive. However, more was yet to come.

Over the next few months, my dad began to get incredibly anxious. First, he was sure that the treatment hadn’t worked. Then, he began to worry that it had spread. Finally, his anxiety took on a life of its own—it seeped into all possible topics of discussion, whether the conversation was about my car needing an oil change or the upcoming rainy season and the possibility of subsequent property damage. Even after we found out that his treatment was successful, he was anxious, fearing that it would come back, or that he'd get another form of cancer. He became irrational, withdrawn, and eventually, completely non-functional. The next two years were rough on my entire family. He was put on multiple medications to keep both anxiety and the side effects of anxiety medication at bay, and this made it harder to figure out what was really going on—his real problems were tangled up with problems created by the medication prescribed to help him. Through therapy, hard work, and (finally!) the right combination of medications, he’s come back to us from that place. However, the effects of the experience remain.

I have always identified with my father, and watching him unravel affected me deeply—we share a sense of humor, deal with the world in largely the same way, and both often shy away from handling tough emotions. I worried that I was watching a picture of my own future if I didn’t learn to deal with my own anxieties and handle my health proactively. I knew I needed a way to quiet that panicky voice.

I first heard about the BRCA gene testing after reading Angelina Jolie's 2013 op-ed about her double mastectomy in The New York Times. I dismissed it initially, partially out of fear and partially because I had heard that testing was expensive. There were many other pieces written at the time criticizing Jolie for advocating a course of care only available to the wealthy, and I simply didn’t think it would be a possibility for me. Then, in 2014, my Aunt Carol’s daughter, Christine, told me that she’d been tested and was positive for both BRCA 1 & 2. I decided to find out whether or not it would be possible to be tested myself.

The truth is that BRCA testing can be expensive for a multitude of reasons, but if there’s a family history of cancer, insurance companies will often cover all or part of the BRCA test— it’s much cheaper for them to pay out for preventative care than for treatment. I made an appointment, requested the test, and jumped through all the necessary hoops to get insurance authorization. I was approved for the test and hesitated for only a moment on the morning I picked up the paperwork and took it down to the lab.

Tests like the BRCA test, tests that might give you information on how to plan for your future—these tests are scary. But I was even more scared to not know, to always feel like something terrifying was around the corner. I was more scared to worry with every ache, pain, and illness that it could be something more. I firmly believe that knowledge is power. I wanted to either know that I had the same odds of getting cancer as everyone else, or that my risk was greater and I needed to be proactive and take matters into my own hands. So, I got the test. And then I got a call.

I was studying at school for a midterm when my phone rang. It was my doctor, and she was as straight-to-the-point as ever: “So, Rosemary. You’ve tested positive for the BRCA 2, and here’s what we are going to do. You’ll have your kids, and then you’ll have your ovaries out. I’ll schedule a consult with oncology for you if you have any questions.” I was stunned; I think I even laughed. I thanked her, hung up, and stared back down at my schoolbooks in vain. Luckily, I’d reached out to some women online and done a lot of reading on my own, so I knew that “having my kids and then taking my ovaries out” wasn’t the only option; even so, neither of those things were demanded of my immediate future.

After all the anxiety I'd pushed down over the years, after all I had watched my dad go through, and after all the hoops I had to jump through with the insurance and the lab, the few tears I shed were more out of relief than anything else. I felt glad to finally know and be out of that limbo space. I was ready to move forward, and that’s what I’ve done in the months that have followed.

My positive test results do not guarantee a future cancer diagnosis; they’re just an indicator of increased risk. According to Breastcancer.org, “For women, the risk of getting breast cancer in your lifetime if you have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 abnormality is between about 40% and 85% — about 3 to 7 times greater than that of a woman who does not have the mutation. Your lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is significantly elevated as well: 16% to 60%, versus just under 2% for the general population." There are many preventative options available, from surveillance to surgery, and there is no one-size-fits-all treatment. In fact, there’s even an interactive online decision tool available to “help those with BRCA mutations make preventative care decisions.” It allows users to input health factors and other relevant information to assess risk, and calculates potential survival rates depending on various courses of treatment.

Personally, I’ve decided to just keep an eye on things for now. I’ve drawn up a plan with my doctors to schedule biannual mammograms and pelvic sonograms to check for both breast and ovarian cancer. I’m also going to practice risk avoidance. I’m not willing to drastically change my life plan for something that isn’t a certainty; I’m in no rush to have kids, and I’m not sure I’ll ever have an oophorectomy. My ovaries regulate a lot of hormonal production and I don’t want to create more problems by taking drastic measures that aren’t right for me or my body, yet. When and if the time comes, I’ll take action. For now, I’m glad that I’ve taken my health into my own hands so that I can make decisions based on knowledge, rather than fear — decisions that make me feel as in control as possible.