Life

The 7 Most Historic Divorces Of All Time

These days, it's so common for famous couples to break up, it's tempting to start a "celebrity divorces" betting pool any time two well-known people exchange rings. (I give Nikki Reed and Ian Somerhalder three years.) But divorces, annulments, and other methods of marital separation among the rich and famous aren't a new phenomenon — and in the past, these splits often led to wars, breakdowns, and legal showdowns, and decided the fate of entire dynasties. In previous historical eras, when powerful people split up, the ramifications were much more severe than just having to give back the wedding presents.

If we're talking famous breakups, there's one myth we need to get out of the way: noted six-time husband Henry VIII didn't invent divorce. It's been around in various forms for a great deal of human history. Researchers have found divorce statements from the Tang Dynasty in China (an era which started in 618 AD) and "divorce contracts" from ancient Egypt. And ancient Greek and Roman society both offered methods to easily get out of marriages — in fact, Romans seem to have basically invented no-fault divorce.

But even within this long history of divorces, there are some that stand head and shoulders above the rest, purely due to their political consequences and high drama factor. If you think Bobby Flay and Stephanie March arguing over her breast implants in divorce court is scandalous, wait till you get a load of these seven historical marital squabbles. We've got trickery, disguises, wars fought over conflicts about exes, and an entire new religion established just to get out of a marriage. Your most out-there soap opera cheating scandal ain't got nothing on these breakups.

1. Caroline Norton and George Norton

Caroline Norton is a little-known feminist hero and legal reformer — and all her work started because she wanted to escape a truly terrible marriage. Her husband, George Norton, was a member of Parliament who beat her regularly, but their three children kept Caroline from leaving. This was because the laws of the day determined that divorced or separated women were not allowed to keep custody of their children. When the two broke up — George brought Caroline to court to allege that she had been having a sexual affair with Lord Melbourne, the Prime Minister, but the claim was thrown out — Caroline mounted a campaign to assert her rights to the custody of her children.

It took three years, but in 1839 the Custody Of Children Act, which allowed wives to be given primary custody of children under seven, was passed in England. Caroline then campaigned for fairer divorce laws, which helped speed along the passage of the Marriage And Divorce Act of 1857. George, however, was an all-around bad egg who refused to let his ex enjoy the rights she had won: after Caroline got custody, he sent the kids to a school in Scotland where the new custody law didn't affect them. He then only allowed Caroline to see them after one of the children died.

2. King Henry VIII, Catherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves

King of England Henry VIII decided to divorce Catherine of Aragon in order to marry Anne Boleyn, as anybody who watches The Tudors knows. But in order to do it, he had to break with the Catholic Church in Rome, and declare himself head of a new religious order that he invented, the Church of England — which, of course, permitted divorces. The decision to divorce Catherine set the Reformation into motion, and made England a non-Catholic country — and frankly, that's as intense a set of consequence as any breakup between two people has probably ever caused.

Later, Henry had a much more conventional split — from poor Anne of Cleves, whom Henry apparently simply didn't like the looks of. (Hans Holbein painted a very accurate portrait of her, which convinced Henry to marry her before he'd met her — but somehow, in person, the magic was lost.) Anne, however, got a good deal: she lived quietly in England for the rest of her life, and Henry regarded her as his sister and asked her advice on political matters.

3. Julius Caesar and Pompeia

Julius Caesar is now perhaps best known for being stabbed on the Ides of March. But before his ignominious end, he ended his marriage to a woman named Pompeia, after enduring a ridiculous and lurid scandal that still influences political marriages today.

The most awkward thing about the whole situation is that poor Pompeia seemingly had nothing to do with it. In 62 BC, Pompeia threw a women-only party at her house for a religious festival, hosted by herself and the Vestal Virgins — but a young rabble-rousing politician, Publius Clodius Pulcher (whose career was filled with stunts like this), managed to get in disguised as a woman, in an apparent attempt to seduce Pompeia. He didn't succeed — but Caesar divorced Pompeia anyway, saying the now-famous dictum that "Caesar's wife must be above suspicion".

4. Lothair II and Teutberga

Lothair II, a king in the Carolingian dynasty in Europe, married the noblewoman Teutberga in 855 AD for political reasons. But Lothair already had a mistress, Waldrada, who bore him a son. As it became clear that Teutberga, for whatever reason, couldn't have kids, Lothair began a long-running campaign to get rid of her and marry Waldrada instead. The whole thing rapidly became ridiculous.

Teutberga was then imprisoned and accused of incest with her brother Hucbert. But after she went through the "ordeal of boiling water" (which meant submerging her hand in boiling water and waiting to see if the blisters healed within three days) and her family threatened war, Teutberga was found to be innocent. Lothair tried again: he got bishops to annul his marriage. Teutberga appealed to the Pope, so Lothair declared war on the Pope, was threatened with excommunication, and finally backed down.

He started again a few years later, after a new Pope was installed, but died before anything could be settled — without a legitimate heir. His kingdom was divided up, and Teutberga escaped to live peacefully in a convent.

5. Charlemagne, Desiderata, Carloman, and Geberge

Charlemagne, king of the Franks, tried to make peace with enemies the Lombards by marrying the daughter of their king, a woman called Desiderata, in 770 AD. Unfortunately, Charlemagne decided he didn't like her and sent her back to her dad after just a year of marriage. The Lombards were understandably a bit miffed.

The bad relations were made worse when Charlemagne's brother, Carloman, died and his wife, Geberge, fled the kingdom with her kids, apparently resisting Charlemagne's offers to marry her himself (how polite). Problem? She fled to the Lombards, who took her in and presumably poked their tongues out at the Franks. War ensued, Charlemagne won, and the Holy Roman Empire began.

6. Louis VII of France and Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine was famously a bit of a handful — she married twice, and both husbands found her slightly difficult to deal with. But the breakup of her first marriage led to some pretty twisted political problems that weren't strictly her fault. She was married to Louis VII of France, and some historians think she goaded him into divorcing her so she could marry Henry of Anjou instead. The couple certainly weren't getting along well: Eleanor reportedly had an affair with her uncle during a Crusade, and produced only daughters, no sons. Louis VII finally decided he could be happy without her land and wealth, and annulled the marriage.

Eight weeks afterwards, she was married to Henry instead. But, while traveling to the wedding, several other nobles attempted to kidnap her — they were hoping to force her to marry them. Henry then argued with her so much that he locked her up in a tower. But Eleanor's story has a happier ending: her remarriage produced the sons that would shape England's future monarchy (one of them, John, was the signer of the Magna Carta).

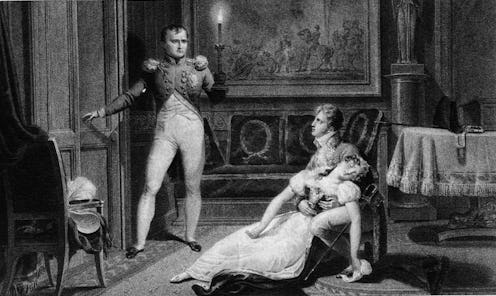

7. Napoleon and Josephine

Napoleon's love letters to Josephine revealed that the French emperor was deeply enamored of his young wife, whom he married in 1796. But that, unfortunately, didn't last, partially because Josephine didn't bear him a son and partially because both of them kept having affairs.

In 1809, Napoleon apparently told Josephine he needed a divorce so that France could have an heir to the throne. Josephine, after a great deal of persuasion, acquiesced. Their "divorce ceremony" actually sounds seriously moving — Napoleon read a statement declaring "she has adorned thirteen years of my life; the memory will always remain engraved on my heart," while Josephine read that agreeing to a divorce was "the greatest proof of attachment and devotion ever offered on this earth." The divorce allowed Napoleon to marry anew and have a child, Napoleon II, and so extend the Bonaparte family's rule over France until 1873.

Of course, any breakup is hard — but the next time you're counseling a friend through one, remind them that at least a whole country didn't have to change religions because of their split. It might provide a little comfort.

Images: Wikimedia Commons