Life

We're Talking About Serious Illness All Wrong

Isolating. That’s the word Cosmopolitan’s beauty editor Deanna Pai used to describe her experience as a 25-year-old second time cancer patient with hepatoblastoma (a type of liver cancer) in a blunt, raw, and angry personal essay within the pages of Cosmo’s April issue. She’s pissed and she’s disconnected, but she’s not alone. A lot of people in these types of critical situations feel isolated, because their family and friends are confused about how to talk to people with serious illnesses.

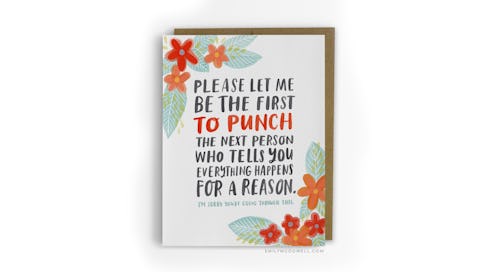

Pai’s personal account of her cancer diagnosis and chemotherapy treatment resonated with me, and then just a few weeks later I encountered the exact same sentiments Pai expressed, this time in illustrative form. On May 3, artist Emily McDowell released her latest creation — empathy cards for people with serious illness — along with a blog post about how her own battle with cancer (Stage 3 Hodgkin’s lymphoma at 24-years-old) inspired a series of down-to-earth, honest, and thoughtful greeting cards. McDowell found most people in her life didn’t know what to say, or sometimes they didn’t know how to say it authentically, because let’s face it — get well soon doesn’t make a whole lot of sense when someone might not get well at all.

McDowell explains that most people struggle to find the right words when a loved one faces a major health crisis, and that’s a big problem because the people we love need support when they’re ill, and we lack the language to provide that support. Her goal is to connect people with each other through truth, insight, and an edgy sense of humor.

“I believe we need some better, more authentic ways to communicate about sickness and suffering,” she says. “[Fuck cancer] is a nice sentiment, but when I had cancer, it never really made me feel better… I never personally connected with jokes about being bald or getting a free boob job, which is what most ‘cancer cards’ focus on.”

Both McDowell and Cosmo’s editor Pai have taken a pretty similar stance in their respective personal essays. Some people in their life may as well have disappeared following their diagnosis, and the loneliness they felt when their friends and family members withdrew from social interaction was like a second stab in the back after cancer took the first ugly jab.

“The most difficult part of my illness wasn’t losing my hair, or being erroneously called ‘sir’ by Starbucks baristas,” notes McDowell. “It was the loneliness and isolation I felt when many of my close friends and family members disappeared because they didn't know what to say, or said the absolute wrong thing without realizing it.”

In Pai’s Cosmo essay, she writes a pretty similar statement with more angry vigor, “I get that people freak out, even friends. But if cancer makes you so uncomfortable that you can’t send me a, ‘Hi, how are you?’ text, get over it. My cancer is very busy making me uncomfortable and cannot seem to pencil you in today.”

Both women also had the same advice: don’t push positive thinking, don’t share your wonky holistic health approaches that worked for your sister-in-law’s cousin’s husband’s aunt, don’t tell me you’re sorry, and don’t make vague offers of help, should I have the energy and audacity to ask for it.

I've been the friend and the family member who didn’t know what to say; I’ve been the friend and the family member who said all the wrong things or didn’t say anything at all. In retrospect, that doesn't make me the greatest friend, but it didn’t come from a place of uncaring. Rather, it stemmed from a place of confusion because our society doesn’t talk frankly about death and serious illness, so when young people are confronted with it, they have very little experience or knowledge to draw upon. Even stories like The Fault in Our Stars and A Walk To Remember, which have become wildly popular movies that bring serious illness to the forefront of cultural attention, don't really speak to the communication struggle that exists. They involve the intimate relationship between two people, which is really a world apart from the experience of trying to be a good cancer friend.

Phrases like, “Let me know if I can do anything for you,” “I'm sorry,” and “Stay positive!” have definitely flown from my lips on more than one occasion. My childhood best friend was diagnosed with aplastic anemia in 2013, and when I visited her in the hospital I was completely out of my element — I don’t remember much of what I said, but other than trying to convince her she needed treatment my sentiment was generally of the stay-positive-variety. Another friend’s mother passed away from cancer a couple years ago, and I felt wholly inadequate to offer much in the way of comfort. My boyfriend’s cousin has a progressive arthritic autoimmune disease called ankylosing spondylitis that permanently fuses the spine, a pretty tragic and traumatic diagnosis to receive in your mid-twenties, and my automatic reaction when I'm in the same room is to skirt the topic, as if pretending it isn't happening means it isn't happening.

Since reading both these women’s stories I've put my best foot forward in an attempt to be more candid and real with people in my life who are ill. I’ve already caught myself on more than one occasion about to say “I'm sorry,” and instead threw a “This sucks balls,” out there instead. I can’t say I’m any more prepared, but simply realizing that people who are sick just want a little honest commiseration and empathy has certainly alleviated some stress. If there’s anything I am good at it, it's complaining about how the universe has wronged me (or you).

Communicating, whether through conversation or greeting cards, in an honest way with people who are sick is as McDowell puts it, “a personal, simple, tangible way to be present for someone struggling with illness.” Let's keep it real.

Images: EmilyMcDowell.com; Emily McDowell/Instagram; Jenn Schleich/Instagram