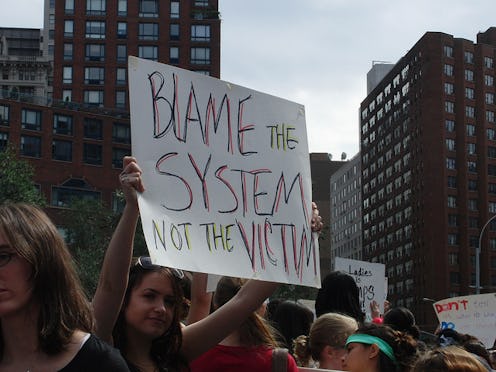

We live in a culture that not only blames sexual assault victims but also tells potential victims, especially women, that it is their duty to make sure they are not assaulted. From date-rape drug-detecting nail polish to difficult-to-remove underwear, the message is clear: We should be trying harder not to get raped. But as Abigail Burdess recently wrote, survivors of crimes like rape and assault frequently find themselves facing blame not only from others, but also from another, more personal source: Crime victims often blame themselves for what they've been through. But why? Why, in spite of the fact that the crime is always the fault of the person who committed it, does victim-blaming continue to happen — and from all sides?

When Burdess was writing case studies on torture victims at the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture to secure grants from the United Nations, she noticed that rape victims often used blaming language towards themselves for the crimes committed against them. And these weren’t victims of atrocities like date rape that victim-blamers normally target. She writes in Standard Issue:

"I’ve heard it over and over: 'I woke up and he was on top of me and I begged him to stop but it was my fault because…' 'I was pulled into a ditch but it was my fault because…' 'I was held in a 4’ by 6’ cell and raped with a gun but it was my fault because…'"

Are these victims simply internalizing society’s judgments, or do they have more deep-seated reasons for blaming themselves? And why do others blame them in the first place?

Burdess had the chance to ask these questions when she interviewed a clinical psychologist about a victim for whom she was advocating. The psychologist responded, "To stop blaming herself, she would have to face the power of the perpetrators over her. And she is not strong enough to face her powerlessness." In other words, what we cannot control, we cannot prevent — and rape victims want to believe they can avoid another assault. Similarly, people who have not been raped want to believe it couldn’t happen to them, so they come up with reasons why they are different from the victim.

Research confirms that people blame victims to convince themselves that they are in control of their destinies. Psychologist Melvin Lerner's experiments established the “just world fallacy” – our insistence that people get what they deserve. In one study, subjects observed someone solving problems and receiving electrical shocks when she messed up. Afterward, they criticized her appearance and personality and said she deserved the punishment. In another study, one of two men was awarded money allegedly at random, but participants still rated the person who got the money as smarter and more competent than the other one.

Further studies have found that people blame victims for everything from car accidents to domestic violence and that victims exhibit the same attitudes toward themselves. One study found that rape victims tend to blame their rapes on changeable behaviors rather than enduring personality traits, further perpetuating the illusion of control.

Still, the contributions of societal misogyny, stereotypes about male and female sexuality (“he can’t help it” and “she asked for it”), and misconceptions about rape (“if she didn’t say ‘no,’ it’s her fault”) to victim-blaming should not be minimized. In fact, these problems contribute to rape itself — and addressing them would be more effective than worrying about what women are wearing.

Unlike policing victims’ behavior, educating people about rape can make lasting progress toward prevention. One study showed that after just one hour of education on sexual assault, men were less likely to believe myths about rape or consider being sexually coercive.

Once we recognize that sexual assault can happen to anyone, we can stop wondering what the victim did to deserve it and start wondering what allowed the perpetrator to go through with it. That’s the only way we can gain the control we crave and create the “just world” we want to believe in.

Images: Peter/Flickr; Getty Images (2)