Books

'The Circle' Makes Us Rethink Social Media

You open a tab and type "g." You press the down arrow. You press Enter. You open a new tab during the 2.3 seconds of loading. In this new tab, you type "f" and press the down arrow and press Enter. You have two notifications. You Like both. You go back to the first tab. You Reply to the first three emails, one from your father and two from coworkers whose last names you notice but will never remember. Every email is signed, "All the best." You do this all day, taking a break at 12:30 to eat lunch alone, maybe in the private room in the office with a door that locks. During lunch, you check your email on your phone seven times and Snapchat your noodles to 15 people.

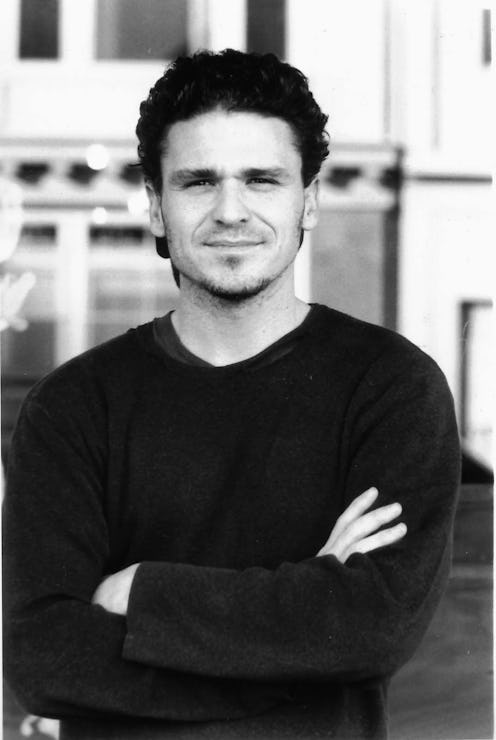

Does this sound like you? Don't open another tab until you read Dave Eggers' The Circle. Set in the future but unnervingly similar to the present, Eggers' novel imagines the dystopia that awaits when the boundaries between private and public knowledge are erased. Mae Holland, an ambitious and bright recent graduate, is thrilled to start working at The Circle, a fictional conglomerate of all social media and tech companies. The Circle has "subsumed Facebook, Twitter, [and] Google," and the company headquarters are perched on an enormous, beautiful campus, complete with dormitories, a bowling alley, and a grocery store, along with everything else workers could ever hope for.

Mae finds out she's very good at her job, which consists of answering consumers' questions and asking them to rate her helpfulness. The time she spends outside of work kayaking or visiting her parents decreases as she continues at The Circle. She's asked to participate more at work — attend events, be active on social media platforms, answer questions about her consumer choices. As she takes on more tasks, she acquires more screens; by the end of the book, she has nine screens on which to communicate and share information. At The Circle, you're ranked for participation, and Mae maintains excellent performance by zinging, commenting, sharing people's stuff.

But as she participates more in the public realm of The Circle, Mae's private life becomes increasingly strangled. She can't get through a conversation with her parents or ex-boyfriend without snapping and sharing a photo or reading aloud a stranger's message. She can't have a conversation with her long-time friend and coworker Annie without Annie worrying that the whole world will know her secrets. Her friendships and relationships with strangers around the world take precedence, and Mae can't sleep at night without word from the Web: a response to an email, a re-zing, a Smile. She's addicted to the feedback loop and cycle of affirmation that The Circle has created.

The character of Mae, whose personality is not remarkable or very complex, is an easy figure to identify with but also judge. One of the most resonant scenes occurs when her ex-boyfriend expresses his criticism of her new job.

You know what I think, Mae? I think you think that sitting at your desk, frowning and smiling somehow makes you think you're actually living some fascinating life. You comment on things, and that substitutes for doing them. You look at pictures of Nepal, push a smile button, and you think that's the same as going there. I mean, what would happen if you actually went? ... Mae, do you realize how incredibly boring you've become?

Cord: struck.

Remember the final scene in The Social Network? Zuckerburg's ex-good friend Eduardo is suing him for shares of Facebook's profit, and after deliberations one day, he sits, alone, refreshing the Facebook page of an ex-girlfriend who he just sent a friend request to. Money, Sean Parker, and one million strangers have replaced the friends he had at the beginning of the movie.

Social media is making us anti-social, addicted to a fabricated, meaningless, and self-perpetuating cycle of feedback. Our typed conversations are imitations of the real thing. Our Internet selves sometimes outshine our real selves: wittier, more interesting, more active and aware. They're easier to maintain and show off.

Where do our Internet selves and real selves start and end, though? At one point, The Circle comes up with a motto: "Privacy is Theft." The statement gives the reader pause for heavy thinking. Is privacy selfish? What do we gain from the privacy we maintain? When Mae loses her privacy, she is no longer impulsive. She has to think twice before swearing, eating junk food, making rash decisions. Is she better off?

Eggers' book brings up issues and themes that we usually acknowledge but mark as "Unread" and plan to come back to later. But you can't Archive this. The Circle demands your attention and careful response now.

The Circle by Dave Eggers, $8.95, Amazon