Editor’s Note: February 22-28 is National Eating Disorder Awareness Week. Each day this week, we’ll be featuring a piece about women’s body image. And remember: If you’re struggling with poor body image or an eating disorder, you’re not alone, and help is available.

In a recent conversation about eating disorders, a male friend told me he regretted that women feel pressure to be his “dream girl” and wishes they knew men liked women with meat on their bones. Well, to my well-intentioned friend — and the many men I’ve heard express this sentiment: my eating disorder was never about you.

My eating disorder was about everything and nothing. It brought up issues of control, self-loathing, perfectionism, and spiritual hunger. But it wasn’t traceable to any of these things. And it certainly wasn’t traceable to the desire to attract men.

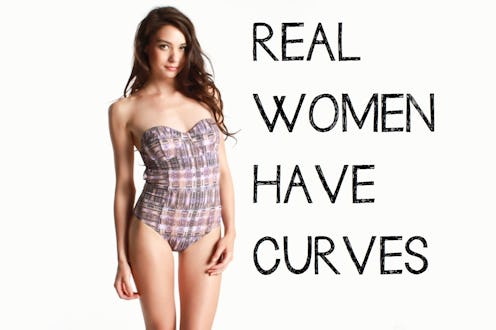

“Men like curves” and "real women have curves" have become a clichés. It is no longer defiant or subversive to say it.

And because the media constantly reminds me that men like curves, from “Anaconda” to “All About That Bass,” doing away with my curves through my eating disorder seemed like a form of rebellion (though not one that I’d advocate).

Over the course of overhearing boys at school talk about girls like walking body parts, watching men leer at women without their permission as a celebrated pastime in classic movies like Animal House and American Pie, fielding violating glances from strange men on the streets, and hearing the occasional tongue-in-cheek warning to my parents to "look out for me" as I physically developed, I got the sense that my body was dangerous.

I often hear men express disbelief that women would starve themselves to fit an ideal that doesn’t attract men. But my eating disorder was not an effort to accommodate men’s preferences.

Developing a body less prone to that danger felt like exercising what little control I had to protect myself, even if it was a false sense of control.

Eating disorder victims have achieved this sense of control through weight gain as well as loss. “I felt safer because I didn’t have to deal with men saying, ‘Nice Tits,’ or ‘Check out her healthy chest,” or grabbing my butt and breasts. It dawned on me that maybe having some weight on me protected me in a way I didn’t otherwise know how to,” Carol Emery Normandi writes in Over It.

In fact, eating disorders are correlated with sexual assault, sexual harassment, and early puberty. This means they tend to develop in women who are taught — especially at an early age — that their bodies’ attractiveness gets them in trouble. Even though harassment and assault have nothing to do with attraction, our culture blames our bodies, and we take responsibility.

My eating disorder was not about attracting men; it was about protecting myself from them.

If my eating disorder was at all about fitting the "Thin Ideal" of female appearance, it was about what that ideal symbolizes: asceticism, perfect, unobtrusive femininity, and yes, desexualization. In The Beauty Myth, writer Naomi Wolf observes that the “anorexic generation” coinciding with rise of Twiggy and other petite icons was also “the pornographic generation,” which grew up with “an atmosphere of increasingly violent and degrading sexual imagery” that women wanted to dissociate from.

I often hear men express disbelief that women would starve themselves to fit an ideal that doesn’t attract men. But my eating disorder was not an effort to accommodate men’s preferences.

More importantly, my recovery was also not an effort to accommodate men’s preferences. It did not require reassuring myself that “he don’t like ‘em boney” or “boys they like a little more booty to hold.” It required unlearning the self-objectification underlying these songs.

The tendency for both men and women to reassure women with eating disorders that men like curves comes from an insidious assumption made throughout our culture that women’s decisions are based on men.

Eating disorders are not decisions, and they may be based on experiences with men, but not in the way you might think. They’re often based on past trauma and the consequent desire to resist objectification — not on a drive to become better objects.

So, to the men out there who want to reassure me that they like curves, thank you for your concern, but I don’t need your approval. Like I said, it was never about you.Image: Grace Messner/YouTube