Something about the 1950s has always seemed a bit magical to me (you know, apart from the political, racial and gender climates of the times). For this, I blame mostly my father. There's a certain inevitability that a child consistently exposed to Johnny Cash, Doris Day and Marilyn Monroe will develop some kind of fascination with the era that introduced us to bullet bras and full skirts, right? But with this fascination, of course, came a fascination with the overall pinup style. I know that back in the day, photos of "pinup girls" were primarily intended to satisfy the male gaze — whether a photograph of a real human or an artistic illustration, the images of these women were meant to be literally pinned to a wall: Sex symbols in front of an audience. There have, subsequently, always been protestors of the entire look/practice as well as supporters. But I tend to understand the support behind the pinup phenomenon because of its "positive post-Victorian rejection of bodily shame and a healthy respect for female beauty." And this understanding has led to the discovery of Hilda: The lost pinup girl of the 1950s. (But also, thank you to my boyfriend for finding her online.)

In conversations with friends and acquaintances about vintage fashion and the 1950s, Marilyn Monroe is always cited as the most iconic pinup girl the world has ever seen. And let's face it: She's probably the first woman who comes to your mind, too, when the word "pinup" is uttered. Part of what I love about "pinup style" is that with it came a certain celebration of curves. Not necessarily of fatness, but of the traditional hourglass figure: Of the tiny waist accompanied by the large breasts and hips. Of a body that juts in and juts out (as most bodies do). Although considered this vital figure in body positivity because of her bombshell curves, the reality is that Marilyn Monroe wasn't a size 12, let alone a 16. By today's measuring system, she was more of a size 2. And ultimately, I cannot help but feel that she didn't really help break stigmatization against women whose bodies are more visibly fat (a fact that doesn't necessarily detract from her brilliance, of course). Hilda, however, is another story completely.

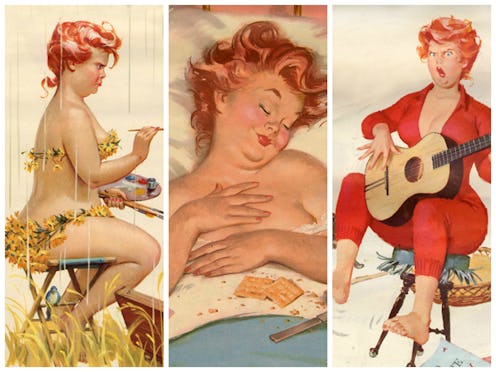

Illustrated primarily between 1957 and 1970 for Bigelow & Brown's Hilda calendars, Hilda was a result of artist Duane Bryers' creative genius. On occasion, inspiration struck Bryers by enlisting the services of plus-size models; but more often than not, he used no model at all. And unlike an Ava Gardner or a Brigitte Bardot, Hilda was more realistically proportioned to represent an average woman: A woman with thick thighs and back boobs and, yes, a double chin.

When we consider 1950s fashion, there is something of a divide: The world was still seeing the remnants of a post-World War II era — one during which it simply wasn't possible to splurge on fabrics, and so pencil skirts and fitted dresses became a norm. But we also began to see economic rising, and the funds needed to develop fashion trends such as full skirts and swing dresses. What I love about Hilda's look is that the styles Bryers dressed her in weren't the fuller, slimming trends and cuts. But rather the body-hugging ones: Bikinis and onesies and things that actually show the fact that Hilda had a fuller figure and that she wasn't remotely ashamed.

It can become difficult to remember that not having a flat stomach and abs of steels is OK when so much of society says otherwise — even to this day, and maybe especially in this day. But it makes me so happy to think that at a time when women were hounded to have the "perfect hourglass," (you know, the beautifully curved one without an ounce of fat to it), Hilda was there as the, "You do you," voice. And she's just so happy! I understand this is a fictional character, guys. I know that she's probably happy because she doesn't have a 9-to-5 job or responsibilities and she just gets to play the acoustic guitar, swim in rivers, read books and play with small dogs all day, every day. But positive representation of plus-size women is crucial to positive body image within girls. Whether you think Hilda is plus-size or not — given the subjectivity of that term — the point remains that she was more realistic. And realism in the media is so, so needed.

Although struggles in body image are not size-exclusive, there is something to be said for relateability. There's a reason we get excited to hear that Mindy Kaling shops at Nasty Gal, or that Tavi Gevinson still wears H&M. And there's a reason we get excited when we're presented with someone like Hilda: This naturally curvaceous but not Hollywood-perfect-bodied woman — whose interests stem beyond her waist size to literature and art and music. Who still has crummy moments of looking in the mirror holding a pair of pants (or a onesie) and wishing she could squeeze into them, because that's what society says she should do. But who ultimately has too much self-love to care, living by the, "You rock," mentality that we have to start instilling in women from a young age. So for that, I applaud Hilda. I applaud all that she stood for — and all that she still stands for. Because we still need her, and many others like her, too.

Images: The Hilda Gallery