Books

Should You Buy Your Way Into Miranda July's Novel?

For me, the space of the story is a sacred one. Try as they might, my troubles never seem to seep into the world fiction creates — it’s sealed off from reality. When my rent’s passed due, I pull up the afghan and settle in with Louisa May Alcott; when I’ve just cried on the subway for no apparent reason, I hunker down with Mordechai Richler; when my cat breaks her leg incurring a vet bill bordering on the obscene, I slip into a little Simone de Beauvoir.

So, what's a girl to do when, late at night, a mysterious email appears in her inbox offering her the chance not only to pre-order Miranda July's forthcoming novel, but also a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to buy real objects mentioned in the fictional work of art?

Well, if you're me, the afghan is simply no longer an option — when the space of the story extends its sticky little fingers into my own all-too-real and very un-fictional universe, fundamental lines have been crossed — there is no turning back. All that's left is to email my editor, rescue the secret chocolate stash from the freezer, and ask the hard question: What happens to the space of the story when its fictional components are being sold to the highest bidder right here in digital, 21st century America?

As I began trying to wrap my head around how, exactly, Miranda July's upcoming online auction represents a clear and present sign of the coming apocalypse, I stumbled upon some of Sam Riley's writing about the long, inelegant history of commercialization in literature. It perfectly captured my distinct breed of vague distrust, fan-girl excitement, and apprehensive paranoia that I'm simply being a stick in the mud. Riley writes that, "Though the commercialization of literature isn’t exactly breaking news, it is interesting to track the ways in which art is being commodified or stripped from its original literary roots and regurgitated into product-form." With this, Riley hits my question head-on: Is July's enterprise bad new for the book, bad news for me, or even news at all?

My head says no, but my heart says yes. The First Bad Man online shop just feels different from my copy of the Gargoyles board game, that allowed me to insert myself into the televised world of Gargoyles, or the original John Waters "Odorama" card kits, which allowed viewers to smell what the characters were smelling throughout his 1961 feature film Polyester.

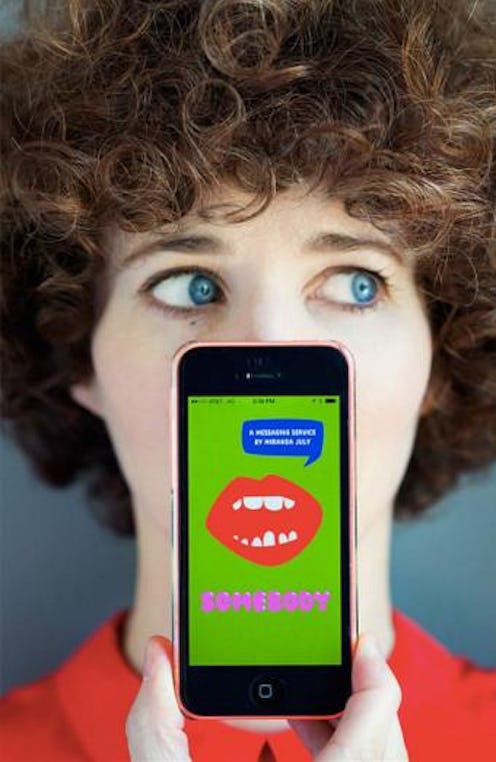

But maybe The First Bad Man Online Shop is different than all that. After all, July's works are traditionally pretty different, right? July has always specialized in a peculiar brand of montage that merges the present moment and the fictional narrative. July's sculptural series Eleven Heavy Things (pictured below) offers visitors the opportunity to interact with stories in the form of sculpture, and in doing so to complete the narrative July has begun. Eleven Heavy Things is like the grown-up-art-world version of the Gargoyles game: you play along; you become a part of the story; and when you're tired, you pack it in and head on home.

Clearly, Miranda July enjoys a story that the reader or the viewer or the visitor can breathe a little life into, and Eleven Heavy Things is just mind kind of sculpture. Yet, this new online shop feels more like huffing and puffing than a breath of life. Where Gargoyles the game, Odorama the olfactory adventure, and Eleven Heavy Things all invite you in, July's online shop blows the roof right off the novel, forcing the fictional inhabitants out into the open, raw, uninvited and right up in my space.

So, despite my reverence for July's work, and my genuine desire to imagine myself as an integral part of the story, I still find myself flummoxed by this new commercialization of the space of the novel; I still feel robbed of a small piece of my serenity; I still feel trampled by an onslaught of capitalism I can neither control nor fully condone.

It's one thing to capitalize on the market for a story, to intensify the experience of the story or to broaden the appeal of a story with literary turbo chargers like a T-shirt baring a beloved slogan, or a tag-a-long scratch 'n' sniff card à la John Waters. But it's an entirely new and different world to treat the story itself as a commodity.

When the fictional stockings, soda pop, fish, flowers, and fresh cut grass all have verifiable commodity value, the world of the story is no longer a wonderland waiting down a rabbit hole, complete unto itself, ever-present, and at the ready. When the world of the story is for sale, it's constantly in flux, it's unstable, it's no longer a place of safety.

That is a pretty chilling thought. So, at this juncture I'm pre-ordering my copy of The First Bad Man and readying my afghan — let's see what Wonderland looks like on the other side of all that shopping.

Images: Miranda July/Twitter; Hannah Nelson-Teutsch ; Giphy (2); Andrealeia/Flickr