Fashion

Can One Book Define Womanhood?

When I was a kid, my dad dressed me in clothes from the boys' section of Nordstrom: turtlenecks, creased khakis, black penny loafers. He adored what he referred to as the "preppy" style, and is a strong proponent of modesty; he found both were best represented in boys' clothes.

I resented my dad's decision then, but at 24, I prize a pair of oversized slacks, a loose T-shirt, and my beat up, coffee-stained Vans sneakers over dresses and heels. I sport short hair that I slick back with pomade. I now know — thanks much to my dad — that femininity is an attitude, and isn't (necessarily) represented in my clothes. What I consider the most feminine aspects of my personality — my outgoing nature and devotion to Jane Austen, for instance — aren't, and shouldn't be, evident in my appearance alone.

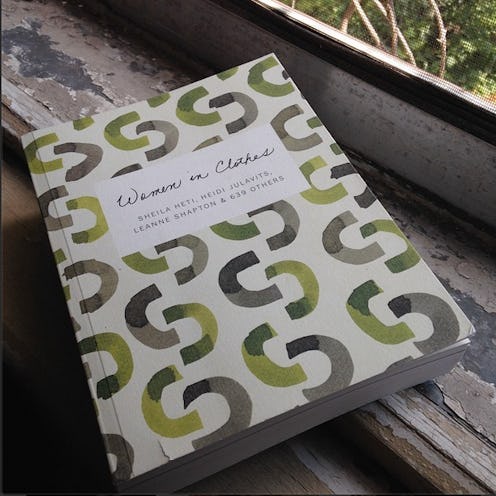

In their new book Women in Clothes , Sheila Heti, Heidi Julavits, and Leanne Shapton asked more than 600 women about their style by having them fill out surveys asking questions like, "When do you feel most attractive?" and, "Do you address anything political in the way you dress?" The provided answers were then arranged according to themes such as "glamour" or "shopping." The book also includes interviews with many different types of authors (painters, filmmakers, and writers to name a few), snippets of recorded conversation between the featured women, and essays on dressing.

Women in Clothes is an important text because it's a reminder of why women value the fashion world: it's a vehicle through which we express our individual versions of womanhood. The book's three editors capture the collective voice of women united by their thoughts on how fashion and style defines (or doesn't) their identities. Their diverse answers illuminate how clothes are connected to almost every aspect of their lives: sexuality, aging, social status. For example: One transgender woman spoke about how she struggled to dress appropriately for the summer during her transition because she discovered how much harassment accompanies revealing clothing. Another woman discussed adopting the Lolita style in Japan as a teenager to express feeling like an outsider at her school.

I realized while reading the book that I don’t just prefer the aesthetic of more masculine attire, but that by choosing to cultivate a style that rejects traditional femininity, I am defining my persona to the outside world. Taken as a whole, these stories create a cohesive narrative in which I found shared thoughts or experiences that helped me better grasp my identity: author Amy Brill admitting that constantly be called small made her tougher, or curator Hikari Yokoyama comparing getting ready to go out at night with being in the studio — "it's meditative and creative" — both reflected the development of my own style: well thought-out, but simple — with just a hint of careless ease.

Women In Clothes, $20, Amazon

This book is also a record of women’s voices talking about their concerns on their own terms. There’s a refreshing honesty to these interviews and conversations, a feeling of uncensored communication that is the opposite of the kind of women’s magazine interviews regulated by publicity specialists to which readers are usually subjected when they want to discuss clothes. The book feels like a community — a support group, even — for women who want to talk about family, and gender politics, and art — anything really — through the lens of fashion.

Women in Clothes affected me so deeply because I had never before read such a diverse representation of women’s voices in a piece of literature before. It fulfilled a longing I’ve been harboring — that I think many other women harbor — when we stalk the aisles of bookshelves, looking for that text that listens to women, that lets us speak for ourselves, and allows women to define our own personhood.

One survey question asks, “What are you wearing right at this moment?” For me, it’s a vintage purple dress covered in black roses with yellow clogs. I feel uncharacteristically feminine.

On one hand, it’s just a dress, but the voices in Women in Clothes contend that that's too reductive: What I'm wearing is a mirror held up to the world reflecting how I view my inner life, with all its complications and intricacies.

I am making up my identity as I wear it: a woman in her clothes.

Images: womeninclothes/Instagram (3); Elisabeth Sherman