Books

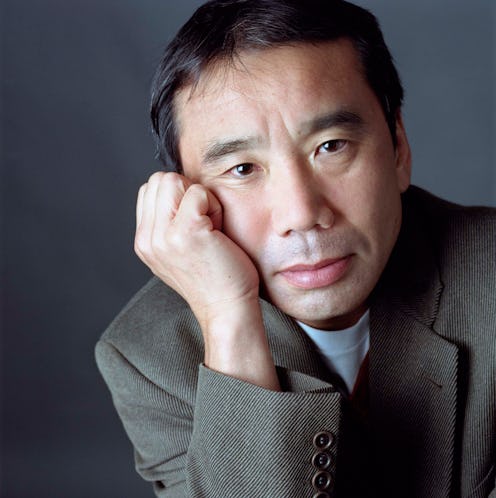

Should You Read the Newest Murakami Novel?

Haruki Murakami's last novel, 1Q84, was a 932-page bestselling tome, released in the U.S. in 2011 amidst great fanfare (though some critics subsequently wondered if it was worth all the hype). Regardless of their experiences with the novel — some loved it, some were more meh — fans and critics still eagerly awaited August's release of the newest novel from the fantastical author, with bookstores across the country hosting midnight book parties for Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (Knopf). Smaller in scope that 1Q84, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki is still pure Murakami, written in the dreamlike style for which the author is well-known.

Murakami's plot moves back and forth through time as if chronology is irrelevant. We see the main character Tsukuru Tazaki in the present moment, a 36-year-old man living his lonely life in Tokyo; as a 20-year-old just abandoned by his friends; five years after this abandonment, inexplicably losing another friend whom he’d come to rely on; and as a high school student forming the bonds of friendship he expected to last a lifetime. In the five months after his high school friends cut him off from their group, Tsukuru suffers from a deep depression that affected even his ability to dream:

But even if he had dreamed, even if dreamlike images arose from the edges of his mind, they would have found nowhere to perch on the slippery slopes of his consciousness, instead quickly sliding off, down into the void.

The reader is pulled down along with these dreams, as the narrative explores the depths of depression. Murakami has constructed a city of loneliness within his character’s mind, which is described as “a rough land strewn with rocks” where “birds with razor-sharp beaks came to relentlessly scoop out his flesh.” Tsukuru is transformed by these months of depression, and though he survives the loss of his close friends and attempts to move past the unanswered question of why he was ostracized, he never really heals. Sixteen years later, he still carries his wounds.

Murakami is well-known for creating alternate realities within his novels (so much so, in fact, that parallel worlds have their own square in the New York Times Haruki Murakami Bingo Game). While there is a parallel world described in the novel, it is subtler than fans may expect, revealed first through Tsukuru’s dreams, which are disturbing to the character and realistic enough to haunt his waking life. Gradually the line between dream and reality begins to blur, for both Tsukuru and the reader. For example, Tsukuru eventually learns why his friends abandoned him all those years ago, and while he has no memory of committing the crime they accuse him of, at the same time he cannot escape the feeling that he was somehow responsible. There is a part of him, he reflects, that might have slipped away and done it, as though in a dream.

This blurring between dream and reality, combined with the jumps in time, create the impression that all the events of Tsukuru's life are all somehow happening at the same time. While this also gives the sense in the narrative that Tsukuru's depression is never-ending, the book is hardly a depressing read, as Murakami manages also to imbue Tsukuru's journey with hope.

While a less talented writer might struggle to tell a compelling story about a colorless and empty character experiencing loss, loneliness, and depression, Murakami's language and imagination hold the reader's attention and demonstrate the connections between loneliness and love. Love pushes Tsukuru to navigate through his nightmares, and to open old wounds so that they might finally heal. The story offers hope for Tsukuru’s future, or at least one version of it, as well as a new way for the character to see himself. He may be colorless, an empty vessel, but as a friend asks him, “[W]hy not be a completely beautiful vessel? The kind people feel good about, the kind people want to entrust with precious belongings.” Tsukuru is such a vessel, and is perhaps not so colorless as he might have believed.

Image: Marion Ettlinger