Books

Books Alone Won't Fix Women's Workplace Problems

Everybody has an opinion about how and why and when women should work. Should they hustle as hard as — or harder than — the CEO dudes? Should they dedicate exactly half their time to family, or abandon family all together, or find a stay-at-home partner to make tempeh meatballs while they ride the corporate bucking bronco? Should they wear suits and ties or harem pants and Louboutins? And most importantly, should they do it all with confidence or sweetness or an impervious, dictatorial attitude that'll freeze out everyone but the boldest of interns?

Everybody will tell you something different. Everybody has written a book about it.

The how-should-women-work debate has been around for decades, but for the past year, it's been vortexing around Sheryl Sandberg's Lean In and, more recently, Lean In for Graduates. Some people deconstruct the book's implications; the rest of us just look around, confused at all the yelling. So we're supposed to lean in now? Is it cool if we don't? Then there was Sandberg's odd "Ban Bossy" campaign, based around an old-fashioned technique — the whole "banning" idea — and reeking of censorship. Commence more standing around looking confused. What if we like being bossy? What if we want to be bossy? What if we don't care if we're bossy?

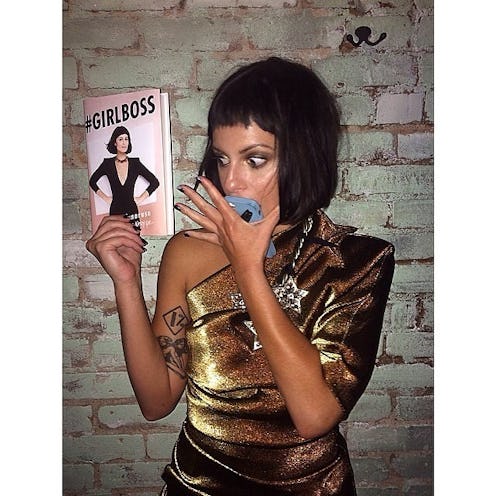

Opinionated Millennials can stop holding their breath, because in May, we got #GIRLBOSS , a book that pairs traditional workplace advice ("your boss is not your friend") with sassy statements about not letting the Man get you down. #GIRLBOSS was written by the founder of Nasty Gal, Sophia Amoruso, and it urges young women to work hard and get rid of their senses of entitlement while still retaining their inner oddballs. It's a perfect book for today's working girl.

I've been trying hard to figure out what I think about the very existence of these books. As a book-reader and an independent working girl myself, do I need publications like this? Do I want publications like this? Do I find publications like this helpful in a concrete way? And I keep coming back to a very simple conclusion: these books are fine, maybe even great, but they're not a solution, and we shouldn't treat them like they are. They're a useful reminder of a pervasive problem, but they're not fixing things.

At their core, books like Lean In for Graduates and #GIRLBOSS are two things: inspirational reads and how-to manuals. I don't mean to discount the very real work that went into both of these tomes, or the very impressive resumes of their authors. But reading about hard work is sort of like reading about a workout plan — you can get through the entire stimulating, inspiring thing without moving a muscle.

A book like #GIRLBOSS is valuable in that it inspires young women, especially young women feeling under confident or unsure of how to carry themselves in the workplace. But it's ultimately a bit shallow; it's a memoir with some pretty basic workplace advice stirred in. This advice — don't let men hold you back, work hard for what you want — isn't really what young workers need to hear. Millennials ostensibly already know that we should work hard and push for equality and wear professional clothing to an interview, and if we don't, that's a different problem entirely. What #GIRLBOSS provides — what Lean In provided — is psychological support, not answers. Change in the workplace ultimately happens with change in the workplace: You gotta go to the interview before you can get the job. You gotta work at the job before you get the promotion. If there's another way around this corporate ladder, neither Sandberg nor Amoruso are telling young women about it.

I have an impressive friend from college named Marcy Capron, who's 27 and the CEO of her company, Polymathic. When I asked her about the books-for-working-women scene, she was far less interested in the debate (bossy vs. not bossy! Lean in vs. lean out!) than one would expect. Why? Well, she's busy working.

Capron puts her feminist energy into creating gender neutral, 50/50 workplaces and developer events — that is, increasing the number of women in her professional circles rather than creating on girls-only spaces.

"Bossiness is a part of who I am and I wouldn't be where I am without it," she says, and she's channeling that bossiness, or what we might call leadership, into creating an ideal balance. "We have to avoid token-ism," she told me, after explaining how she'd been the "token woman" at speaking events one too many times. In short, Capron isn't reading the how-to books, she's being a girl boss. Done.

I'm not interested in discounting or unfairly devaluing any of these books. I think their existence is a good thing. Books like #GIRLBOSS always lead to interesting dialogue about feminism, hard work, and womanhood, which is fantastic. But we shouldn't treat these books like saviors of the working women. They encourage, but they do not answer. They point out problems, but they don't in-and-of-themselves fix them. And they tend to focus so much on vocabulary — "Bossy?" "Suavely confident?" Who cares? — that they distract from bigger issues. If you read the book and talk about the book but never do the work, women like Capron and Sandberg and Amoruso will still be the token woman, the rare "female success story," in a room full of dudes.

Image: @sophia_amoruso/Instagram