Books

Q&A: Galchen on Psychiatry and Female Narrators

"It's important to avoid mirrors if one is unprepared to accept the daily news," the narrator muses in the titular story from Rivka Galchen's new collection American Innovations (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). The narrator is one of many female voices in Galchen's latest work, who's strikingly un-striking: wandering, unaware of her place, and awash in uncertainty. These narrators have a sometimes infuriating, sometimes delightful distance from reality that seems both intentional and totally accidental on Galchen's part.

Case in point: the "Innovations" narrator's relationship with mirrors and doctors. She only learns that she's grown a third breast when she passes an unavoidable mirror. A doctor advises her:

You might want to think about this new part of yourself. Just take some time and think about it. Do you really want to change yourself just to suit fashion when you don't even know what fashion will bring next? That may not be the person you want to be.

At times like these, Galchen's characters seem to be directly stating her views of the world and writing fiction. Her stories combine elements of her own experience with layers of the very strange and unexpected, and she often sums up pivotal moments of plot with a few sentences and a wry comment. In American Innovations, Galchen's talent for presenting faintly sad, off-beat narrators is fully palpable and makes for compulsive reading. And though it's not obliquely obvious (unless you read the jacket copy), her narrators are the female, rewritten voices of the legendary stories of writers past: Borges, Bolaño, Gogol. I picked Galchen's brain about psychiatry and writing; how she, like the "Innovations" narrator, doesn't like mirrors; and female narrators.

BUSTLE: These stories are so distinctive and original, but, as the jacket copy says, "are in conversation with canonical stories" from Thurber, Borges, and Gogol. Do you see your stories as homages, or as reimaginings?

RIVKA GALCHEN: It didn't become very conscious until fairly late in the process, so I feel like it was more like the source stories were the weird banquets I ate at and then my stories were sort of like the vivid dreams that come after eating lots of mousse and quail. Or moose and kale.

You were in psychiatry before going back to school for your MFA. How does being a psychiatrist inform the writing process?

I never practiced as a psychiatrist, though it was my main interest while I got my MD. I liked psychiatry and I like ER medicine, I think because they are both strange extremes of contact with strangers. Writing is also a sort of contact without contact, like certain branches of medicine. It's intimate, and yet also removed and boundaried. Maybe I like writing more because the boundary is more unbridgeable, but also more invisible.

Writing is also a sort of contact without contact, like certain branches of medicine. It's intimate, and yet also removed and boundaried.

So many of your observations of your characters are subtle and yet, upon rereading, add up to a bigger story. Do you diagnose characters — come up with symptoms and causes — before you write them?

I know this sounds cheesy, but I feel like, for me, writing is more like archaeology than like sculpture in terms of what you end up with … and so, I feel like I discover things about these characters along the way, and the writing process is more a kind of stratigraphy.

Do you read reviews?

Not really. And I don't look in the mirror either. But I do love editorial feedback. And shiny things.

Well, you're compared to Woody Allen in the New York Times . Which writers or artists would you compare yourself to?

Well, there's so many people I admire, but I don't know if I would compare myself to them, though of course there are people I aspire to be more like, at least in intensity and labor. But, for another film aspiration, I love, love, love, love, love, love the work of The Coen Brothers. And I do think the way there's an underlying formalism to their stories that they use as a kind of method for making something genuinely moving … and the way they have these 'random' details that feel like a slipping of the pen … and the way they are somewhat seriously silly … those are work habits I recognize, and am trying to develop.

I used to be weirdly anxious writing in a female voice — the voice always sounded wrong to me!

My favorite characters and narrators of yours are female — Trish in "The Entire Northern Side Was Covered in Fire" and the narrator in "The Lost Order" are witty and straight-up. Do you find the female perspective easier or more gratifying, in some way, to write?

I used to be weirdly anxious writing in a female voice — the voice always sounded wrong to me! This was something about myself that really annoyed me. And I think, eventually, annoyed me so much that for awhile I could only imagine writing from a female perspective. Maybe I'm still in that phase. Though I find that the female voices of my stories are, in some ways, somewhat 'masculine' … and that my male voices are somewhat 'feminine' … which might just reveal that I don't really know what I mean by feminine and masculine when it comes to voice.

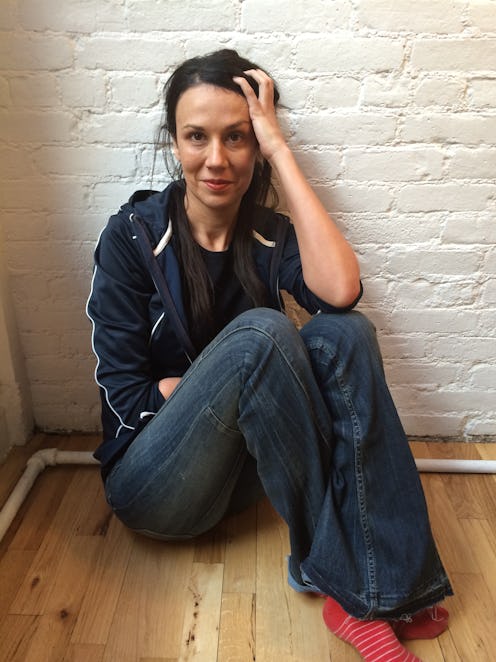

Image: Sandy Tait