Entertainment

'Troy' Is Ridiculously Inaccurate, & Here's Why

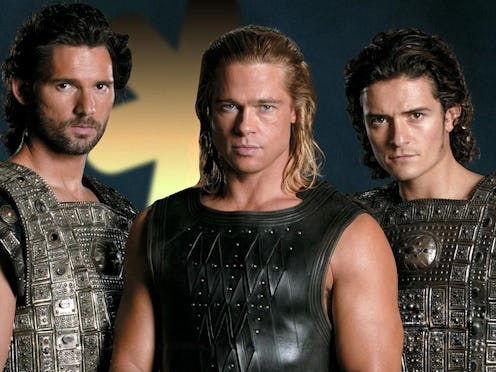

As a student of screenwriting, I understand full well that, in the quest to adapt a book to a film, there are certain concessions that need to be made. Literary nuance gets visualized, novelesque plot arcs crunched into a crisp three-act structure, and certain characters are simply destined for the cutting room floor (RIP, Peeves). However, there are some movies that take wild, inexplicable, unforgivable liberties with their source material, purely for the Hollywood of it all — and perhaps the most egregious of these, at least to my mind, is 2004's hunky-dudes-in-armor vehicle Troy . Yes, even beyond the leather kilts and sincerely regrettable haircuts, the film adaptation of Homer's Iliad was so blatantly, stupidly inaccurate that it still stokes my ire 10 years later. So, on the occasion of its decade-old anniversary, let's take a minute to pshaw once again at some of the more baffling alterations made to this classic war story (while doing our best not to wear out our keyboards with interrobangs, that is).

Patroclus was Achilles's "Cousin," Instead of his Lover

While the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles is never explicitly described in The Iliad, other works by the likes of Plato and Aeschlyus portray the characters as lovers — and Homer certainly doesn't do anything to discourage that interpretation. In fact, Patroclus's death at the hands of Hector is the major motivation for Achilles's subsequent grief-fueled killing spree, his controversial disrespect for Hector's corpse, and ultimately, as prophesied, his death. In the film, however, the writers chose to trump up Achilles's relationship with a captive priestess, Briseis (hi, Rose Byrne!), from "I'm pissed because Agamemnon wants to take her away" to "doomed love between kindred souls," while downgrading Patroclus to the role of "cousin." And boy, do they really hammer that one home, every time he's even hinted at: "Oh, you mean his cousin?" "Yes, his cousin." "Are they cousins, though?" "Indeed, that Patroclus is his cousin. Definitely, 100 percent cousins." It's essentially the filmmakers' version of an Ancient Greek "no homo."

Of course, this change is particularly irksome because it's entirely illogical plot-wise — diluting Achilles's revenging anguish over losing a lover to "Graah! Basic familial loyalty!" — and moreover, because it was clearly altered to appease homophobic censors afraid a sexual subplot between two men wouldn't fly in Peoria. Not only would leaving in the nuance of their relationship have created a much stronger motivation for Achilles's ensuing wrath, but also, it would have given some excellent visibility to a bisexual character, reminded the testosterone-hyped teen market that queer dudes can wield a sword with the best of 'em (or, in this case, better) — and, most importantly, we would probably have gotten to see Brad Pitt make out with Garret Hedlund, which, um, yes.

I mean, come on — tell me there's not some serious tension in all that "sparring"...

Helen Never Felt at Home in Sparta — Except, She was Born there

This is a pretty small one, sure, but it's frustrating, if only because it's so pointless. Setting aside the fact that casting anyone as Helen is problematic — because she's supposed to be The Most Beautiful Woman Who Ever Lived, and no actress can realistically meet those standards, not even the eminently lovely Diane Kruger — the writers chose to explain her motivation for suddenly absconding across the sea with Prince Paris (AKA, puppy-faced Orlando Bloom) by giving her a melancholy monologue about how "Sparta was never my home — my parents sent me there when I was 16, to marry Menelaus."

To which I sigh a resounding "Nope": Helen's parents were the King and Queen of Sparta, and she chose Menelaus out of a suitor pool that included all the eligible men in all the land — essentially like a toga-sporting Bachelorette. In fact, the pact that Odysseus forced all of Helen's suitors to swear to at this particular gathering — that they would all pool their resources and fight anyone who tried to steal her away — is the impetus for the Trojan War. But, no: In the film version, she's a miserable child bride who's married to an insensitive oaf, and Agamemnon goes to war essentially because he feels like it.

And, speaking of Menelaus...

Menelaus dies, which, just, no

For those of you who remember your Odyssey, you may recall the scene in which Odysseus's son Telemachus swings by Sparta twenty years after the war to check in on Menelaus and Helen, who tell him some cool stories about his dad. Of course, that can't happen if Menelaus was already stabbed to death by Hector after Paris chickened out of their duel — which, you guessed it, is how the film chooses to have things go down.

Then Agamemnon dies, which, ?!?!?!?!?!

While audiences could certainly survive without that wee detour in the story of Odysseus's long journey home, the fact that the filmmakers chose to stab Agamemnon in the gut during the final climactic battle effectively cancels out an entire series of plays — Aeschylus's Oresteia, the story of Agamemnon's return home, his murder by his wife and her lover, and his son's ensuing vengeance. Sure, it may be momentarily satisfying for audiences to watch one of the story's primary villains get eviscerated — and Brian Cox does rock a mean death scene — but it's a cheap catharsis that feels unearned, even in the warped world of the film, and is ultimately trumped by the butthurt of its inaccuracy.

I mean, sheesh. As if making us look at that rats nest on the back of Eric Bana's head wasn't enough.

Images: Warner Bros. Pictures