News

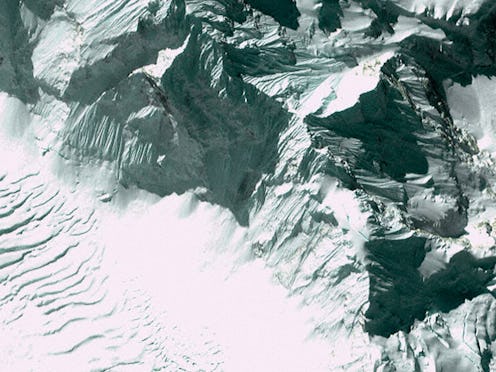

How Safe Is It To Climb Mount Everest These Days?

In the wake of an avalanche that killed 16, Sherpas tasked with leading climbers up the icy slopes of Mount Everest want to shut down Everest for the season. Climbers and expedition leaders evacuated the base camp Tuesday as the Sherpa community continued to mourn those killed in last Friday's accident. With tensions rising between the mountain's caretakers and the Nepalese government, the question remains: Is climbing Mount Everest now safer than it used to be?

When Jim Whittaker became the first American to reach the summit of Mount Everest — with Sherpa Nawang Gombu — in 1963, the mountain was quiet, desolate and treacherous. At the time of Whittaker's landmark ascent, only six climbers had made it to the summit, which is approximately 29,002 feet above sea level. The mountaineers who preceded Whittaker only made one trip up Everest's soaring slopes (Gombu was the first person to successfully climb Mount Everest twice).

A lot has changed since those historic expeditions. Mount Everest has become a commercial industry, generating millions of dollars in mountaineering tourism each year. The New York Times reports that the Nepales government takes in $3 to $4 million each year just in climbing licenses, which were recently reduced from $25,000 to $11,000 per person.

Since Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay conquered the mountain in 1953, more than 4,000 people have reached the summit. In 2012 alone, nearly 600 people completed the excursion, representing a 56 percent success rate. Just 20 years ago, the success rate was 18 percent.

But do more climbers — and consequently, more money — mean less safety risks? Not always, say the Sherpas. Yes, new climbing gear, such as stainless steel ice axes, lightweight sleeping bags and well-insulated suits and base layers, has certainly made the trek easier for climbers. Plus, technological advancements have made two-way communication possible, as cell service is now available in the region. (Back in the day, climbers relied on radios.)

However, the tourism boom means that the Sherpas have to deal with more inexperienced climbers. According to Sherpa Pemba Janbu, foreign clients were forcing he and his colleagues into dangerous situations:

Climbers actually say, ‘I’ve paid $50,000, you are here to work for me, and you have to accompany me. ... The mountain itself feels like it is losing its value. Just about everyone seems to want to climb it by paying a Sherpa who will ensure reaching the summit.

The mountain's crowded paths can also pose some risks. German mountaineer Ralf Dujmovits lamented in 2012 that Mount Everest was now being treated as "a piece of sporting apparatus." He told The Guardian that the increased in "hobby climbers" could mean more accidents and deaths, as many of these climbers are not physically fit, suffer from exhaustion and tend to misuse equipment like oxygen tanks:

In fact it takes no skill to do what most of the tourists to Everest do. The growing trend in the last 10 years has been to use oxygen almost from base camp onwards, whereas for decades it was only considered to be normal to use it from 8,000m onwards. ... Nepalese organisations are picking their customers from the internet without any concern as to whether they are capable of the journey.

And now scientists are worried about climate change's effect on the mountain. According to The Associated Press, warmer temperatures may trigger more snow, ice and rock avalanches, and make the chartered terrain more unsteady than ever before.

Avalanches have long been greatest risk factor for both climbers and the Sherpas in the Nepalese region. According to The Himalayan Database, there were 608 "member" deaths and 224 "hired" deaths on mountains in Nepal between 1950 and 2009, with avalanches the leading cause of death. About 240 people have died so far while attempting to climb Mount Everest, and the numbers seem to rise as the paths become more crowded. The highest-fatality incidents have happened in the last 20 years, including the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, which killed eight people. It was the worst tragedy on the mountain until last week's avalanche.

Nepal now finds itself in a tough position. The country continues to struggle financially — the per capita income was $1,500 in 2013, while roughly 25 percent of people live below the poverty line — and adventure tourism has become one of its biggest revenue sources. But with the overworked Sherpas ending the climbing season for good, it may be time for the government to give back to the people who have presided over Mount Everest for years.

Image: Sam Hawley/Instagram