Nibbling on an arsenic wafer here, dipping into your pot of ammonia face cream there — your beauty routine in the 1800s would look a lot different than it does now. Whereas currently your morning gambit might be all dry shampoo and mascara tubes, a hundred years ago you'd have a more interesting array of beauty products to choose from behind your mirror cabinet.

If you think it's annoying to remember to put on your SPF moisturizer today, you should see what our foremothers had to sign up for. During a period where makeup was seen as something crass and would get your name brought up during the gossip hour of lady tea luncheons, dabbing on rouge and dusting on powders was a risky game — not that that slowed down beauty routines. During a time where charcoal biscuits were beauty supplements and a Tuberculosis diagnosis was the look du jour, women got crafty with their cosmetics.

Glass bottles holding skin creams and powders were hidden into prescription bottles that were bought at an apothecary, the pills tossed out and replaced with lead face powders and arsenic shadows; mascara and eyeliner were made with a spoon over the fireplace. While a contour palette and $10 beauty sponge might seem like jumping through hoops, it's child's play compared to Victorian women. See what you'd have to do each morning if you were a beauty lover during the 1800s.

Now: Swish Mouthwash, Then: Nibble On Charcoal Biscuits Or Burnt Bread

In order to get your morning breath under control, you'd forgo the Colgate and instead daintily nibble on a charcoal biscuit, staining your teeth black while politely asking for another cup of tea. So metal.

"Bragg’s charcoal biscuits, which are still sold today, were thought to be effective in treating this problem," Carolyn Day, assistant professor of history at Furman University in South Carolina and author of soon to be published book Consumptive Chic: A History of Fashion, Beauty and Disease, shares in an email interview with Bustle. "The Lancet (a premier British medical journal) in 1863 suggested 'the use of Bragg's charcoal biscuits' for the 'distressing complaint' of foul breath." The author then went on to recommend other treatments, such as a chlorine mouthwash.

But if you didn't have a pantry stocked with market biscuits or bottles of chlorine, you could also use household substitutes to get your rank breath reeled in. "A suggested recipe from The Ugly Girl Papers — Hints for the Toilet (a beauty book from 1874) would be to rub one’s teeth with ashes of burnt bread, or to make a paste of ashes and honey," Alexis Karl, perfumer and lecturer at Pratt Institute who's done extensive research on Victorian cosmetics, shares in an interview with Bustle.

So those were your options: burnt toast crumbs or chlorine. The price of beauty.

Now: Buy Perfume From Department Store, Then: Make It Out Of Wine

According to Godey's Lady's Book — the Victorian era's version of Vogue prior to the Civil War — a woman didn't have to spend a pretty penny at a department store for bottled perfume. Instead, she could make a scent at home.

In order to create the cologne water following the recipe in an 1855 clipping, you would have to combine herbal oils such as rosemary, lavender, cinnamon, and lemon into distilled wine the night before, and in the morning you'd shake the mixture well and dab behind the ears. What you would have was a concoction just as sweet as an Parisian eau de toilette — allegedly.

Now: Put On Liquid Eyeliner, Then: Make It In The Fireplace First

Makeup was seen as an impolite taboo during the Victorian period, one where gentle ladies of society wouldn't be caught painting their faces with pots and paints. But, of course, everyone still did it — they just had to be sneaky about it. "Although the use of cosmetics became more restrained, there were a large number and variety to choose from," Day points out. While the most popular vanity mirror techniques concentrated on whitening face powders and rogue, some women emboldened themselves enough to try eyeliner and mascara.

But they couldn't just swing by the corner drugstore to get a pencil of kohl. Instead, they had to make their own. "The most common mascara preparation was lamp black, made by burning a candle and putting a dish close to the flame. The black soot left behind was used with a little bit of oil to darken the lashes or brows," Gabriela Hernandez, author of Classic Beauty: The History of Makeup and founder of Besame Cosmetics, explains.

Classic Beauty: The History of Makeup by Gabriela Hernandez, $107, Amazon

Another recipe had more of a Pinterest-fail feel to it, including ingredients like milk and burnt toast. "The Ugly Girl Papers mentioned using the remains of burnt bread on one’s eyes as a delicate eyeliner. Another option was using the sticky residue of nitric oxide from mercury mixed with lard, which was then applied to thicken lashes and rinsed with warm milk," Karl explains.

And you thought wielding liquid eyeliner was hard.

Now: Make Yourself Look Dewy With Highlighter, Then: Try To Look Like You're On Your Death Bed

Victorian women had this pension for making themselves look like they just came out of a fever dream: To look pale, flushed, and just on the brink of Consumption was the look du jour for the stylish women in the 1800s.

When makeup was worn, it was used to emphasize that weakened state. "The brink-of-death look embodied a certain delicate nature that Victorians found attractive," Karl explains. "There was a definite romanticism linked to ill-fated Victorian heroines of many Victorian novels and poetry, and that a women, seemingly in the hands of death, (watery eyes, pale skin, flushed cheeks,) was all the more beautiful when facing her demise."

While the mysterious allure of dying was seen as fashionable, Day points out that it could be argued that the look was always classically beautiful to begin with, "Tuberculosis could be considered beautiful, in part, because its symptoms were in keeping with those things that were already established as attractive in women. For instance pale skin, rosy cheeks, bright dilated eyes, dark eyelashes were acknowledged components of beauty, but were also the symptoms of the disease." So it wasn't so much that they wanted to look like they were actually on their death beds - they just enjoyed that fragile, feminine look that came with the symptoms.

Now: Treat Yourself With A Bath Bomb, Then: Take A Bath In Radioactive Material (No, Really)

So how would women achieve that frail state? From drawing dark bags to using lemon juice to create watery eyes, they got crafty. According to Karl, a regular regime included skin washes made of ammonia and rose water, radium baths (a radioactive element) to help create delicate, pearlescent skin, mercury rubbed onto eyelashes overnight to help lengthen them, and rubbing red flowers onto their lips and cheeks to create an artificial flush. They also dropped belladonna (a poisonous plant) into their eyes to dilate them and make them bright and watery.

Now: Leave Your Makeup Scattered On Your Sink, Then: Hide It In Medicine Bottles

When you achieved just the right touch of Tuberculosis with your makeup, you had to store away your pomades and creams so as not to let anyone in the house know you altered your appearance. In lieu of stuffing your paints and powders into a loose floorboard under the bed, you would be clever and hide them into medicine chests that you bought from the pharmacy.

"You could get set-ups from druggists that would basically look like a box of medicines but would actually be used to create cosmetics," beauty historian Alex Nursall shares in an email interview with Bustle. Often times they had secret compartments where you could stash some of your more incriminating pastes, but the norm was to store cosmetics among the bottles and viles of prescription tonics and balms. If someone would stumble upon it in your bedroom, they would just think it was a respectable medicine case.

Now: Put On Anti-Aging Cream, Then: Sleep With Steaks Tied To Your Face

If you wanted tips on how to keep your complexion wrinkle free, then you'd thumb through The Arts of Beauty; or Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet, an 1858 book by Lola Montez, a Victorian era actress and dancer, powerful mistress, and the cause of the Bavarian King losing his crown.

Her book shares the beauty secrets of glamorous bohemians and European noblewomen, since she rubbed elbows with famous actresses and royalty alike. One such tip in her book shared how wealthy women kept their skin youthful even as years approached them, writing: “I knew many fashionable ladies in Paris who used to bind their faces, every night on going to bed, with thin slices of raw beef, which is said to keep the skin from wrinkles, while it gives a youthful freshness and brilliancy to the complexion.”

If you thought your peel-off masks were creepy to lounge around bed in, this is a whole other level.

Now: Use A Hair Dryer After You Shower, Then: Grab A Pan Of Coals

If you didn't have the time to air dry your locks after washing them, an 1858 book called Dick’s Encyclopedia of Practical Receipts and Processes , recommended a process that could either save you some time or get rid of all of your hair altogether. Either way, your problem would be solved.

In his chapter he suggests that the woman should lie on a couch with her long hair hanging over the end. Underneath her damp locks would be an ignited pan of hot charcoal peppered with benzoin powder (which is resin from a rain forest tree that smells like vanilla,) and the thick smoke would both dry and perfume her hair. That is, if it didn't catch it on fire.

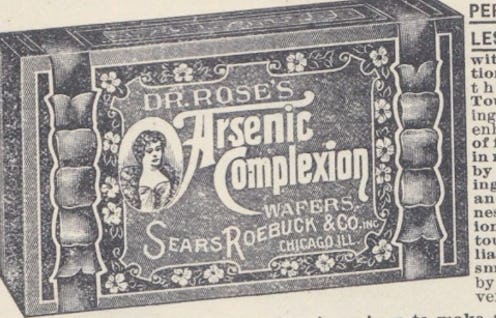

Now: Use Foundation To Even Your Skin Tone, Then: Eat Arsenic

In addition to your blue-tinged face powders, you'd eat a snack during breakfast that would help your complexion stay sallow all day long. Sears & Roebuck sold a popular morning biscuit called Dr. Rose’s Arsenic Complexion Wafers, which were just what they sounded like — chalky wafers dusted with arsenic for light snacking.

While arsenic would have the nasty side effect of kidney and nervous system damage, it would also cause pigment loss, giving you a permanent, pale complexion. While that seems like a risky trade off, this wasn't a case of false advertising on the biscuit box: Women knew the dangerous side effects but kept nibbling away.

"Women knew the dangers of arsenic, as it was used as a rat poison in many a Victorian home, yet women would eat it nonetheless in the name of beauty," Karl confirms. "Arsenic wafers were used by many women to create clear, pale complexions. The amount of arsenic in one wafer was not deadly on its own, though ingesting them on a regular basis would build up a tolerance in the body, and when women stopped ingesting the arsenic they could become terribly ill from the withdraw of the poison."

It was like remembering to take your fish oil and omega vitamins... just, you know, poisonous.

Now: Clip On Hair Extensions To Get The Style You Want, Then: The Same!

The Victorian era was known for their elaborate braids and knots, and their Elaine Benes like poofs, and to achieve it they used the help of clip-on extensions to add volume and more intricate weaves. But while a lot of hair was necessary in order to create those lady-like hair trends, women also needed them since they'd scorch their hair with curling irons that came straight from the fireplaces.

"Women did a great deal of damage to their natural tresses with hot irons, and hair was never cut unless a women became ill. Extensions would be wound about the natural hair, and could provide volume and extra braiding needed for the various styles of intricate rolls and knots," Karl shares.

Looking over these makeup routines woman had to go through a little over a 100 years ago, it makes you appreciate your easy liquid lipstick and hair straightner a little more. But it also makes you wonder how people will look back on our trends a century later and snicker — what in your makeup case is going to sound like the equivalent of poisonous drops in your eyes? Only time will tell.

Images: Bragg's (1); Godey's Lady's Book (1); Alfred Stevens (Belgian, 1823-1906) ~ Girl Looking in the Mirror (1); Jean-Léon Gérôme(1); The Lady of Shalott and the 'Cult of Dead Women' (1); Combing My Lady's Tresses by Jean Baptiste Beranger (1); Sears (1); Boucher (1); vanity john william waterhouse (1); PBS (1)