Today I learned that Gabriel García Márquez had a surprising editor: the late Cuban dictator, Fidel Castro. To be perfectly honest, I have no idea what to do with that information. This is kind of like the moment you find out that Cleopatra lived closer in time to the opening of the first Pizza Hut than the building of the Great Pyramids — not quite world-shattering, but certainly world-shaking.

As it turns out, there is a whole book devoted to Gabo's friendship with Castro. Stéphanie Panichelli-Batalla and Ángel Esteban explored the decades-long relationship between the Colombian author and Cuban president in their 2009 book, Fidel and Gabo. Panichelli-Batalla tells Public Radio International that the two men's editing dynamic, in which García Márquez would send his manuscripts to Castro for copy editing and fact-checking, made more sense than not:

Many people say that Fidel was an eager reader ... He would read all the time. You would give him a book one night and the next day he would have read it and have excellent comments on the book and great constructive feedback on it. And so, he even became one of the first reviews sometimes of Gabo’s books. [sic]

Castro and Gabo first met in Cuba in 1959, but did not establish a relationship with one another until 1977. At the time, García Márquez "was working on a nonfiction book about life in Cuba under the US embargo, using testimonies from ordinary Cubans." He never published it.

García Márquez began sending his unpublished manuscripts to Castro when the dictator found an error in boat-speed calculations in The Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor. He later corrected "the specifications of a hunting rifle" in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, and frequently identified gun-related errors Gabo made in his writing.

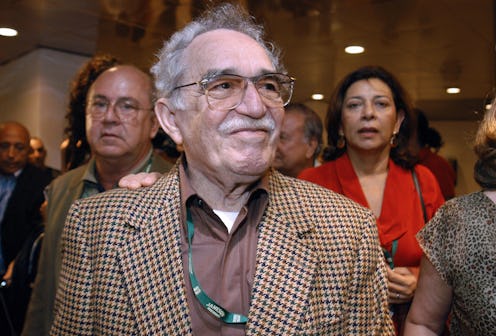

Although Love in the Time of Cholera and One Hundred Years of Solitude cemented the Colombian Nobel laureate's place in readers' hearts, articles published following his death in 2014 highlighted the controversy over his close friendship with Castro. Gabo continued to align himself with the dictator after Castro voiced support for the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in the late 1960s, and in spite of his numerous human rights abuses.

The Guardian reports that García Márquez "would criticise the Cuban president to his face in private but never in public." After receiving his U.S. visa in the 1990s, Gabo spoke with then-POTUS Bill Clinton about the situation with Cuba, saying, "if you and Fidel could sit face to face, there wouldn’t be any problem left." Those talks led to the release of "a number of dissidents," according to Panichelli-Batalla.

Image: wordsandmisadventures/Instagram