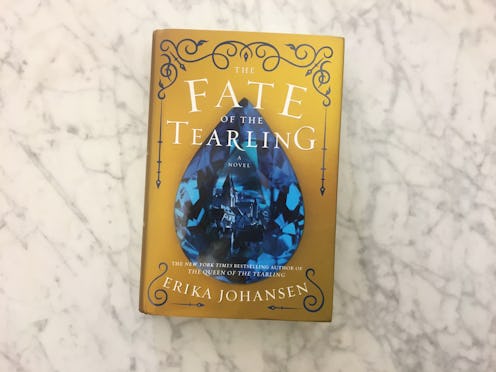

Fans of Erika Johansen's Queen of the Tearling series have been waiting well over a year to discover how the battle between Kelsea and The Red Queen will play out. On Nov. 29, the New York Times bestselling trilogy will reach its thrilling conclusion with the release of the third and final book, The Fate of the Tearling. Here's a teaser if you can't stand to wait two more weeks: author Johansen has shared a Queen of the Tearling short story exclusively with Bustle. Read "The Boy" below, and see if you can guess who it's about!

For the uninitiated, The Queen of the Tearling series follows Kelsea Glynn — set to be played by Emma Watson in the forthcoming movie — a 19-year-old girl who ascends the throne of her nation after a childhood spent in hiding. But Kelsea knows little about the mysterious, haunted past of the country she now rules — and she doesn't know who she can trust in her battle against The Red Queen, the ruler of Mortmesne. Can she depend upon The Queen's Guard — particularly its leader, Mace, and her paramour, Pen? Or should she place her faith in The Fetch, the anonymous leader of a criminal gang who sneaks into her chambers at night?

In the final book, readers will discover whether or not Kelsea can wield her magic and her power to defeat the army of Mort and its Red Queen.

In the short story below, Johansen transports readers to a time before the invasion of Mort. She spins a tale of one physically strong, but emotionally vulnerable boy who's ultimately destined for greatness. Read it below, and pre-order The Fate of the Tearling now:

The Boy

“Boy! Over here now!”

The boy looked up from his meal, a well picked-over rib of beef that had been left carelessly in the tunnel outside. There was still meat on the bone, and before he acknowledged the man who had entered the room, the boy was determined to gnaw away the last bits.

“Boy!”

The boy looked up, resigned. There was no light here but a single candle, its thin illumination barely enough to reveal the shadowy figure in the doorway. But still, the boy knew the man: a portly figure whose boxing muscle had long since run to fat, whose thick jowls and bright red nose revealed overfondness for drink. The boy would know this man anywhere. He would know him on his dying day.

Casting the bone into the corner, the boy popped to his feet. Some days he got enough to eat, some days he didn’t, but either way, he always had his reflexes. They had spared him several beatings at the man’s hands when he was much younger. But the man rarely tried to hit him anymore. The boy thought the man might be scared of him now, although the man still topped him by three inches and nearly a hundred pounds.

The boy would know this man anywhere. He would know him on his dying day.

“Come on. It’s time.”

The boy followed the man out into the corridor, their footfalls echoing off the stone walls. From time to time they would pass open doorways, other entrances, and the boy could see people inside, could see everything they were doing. Most of the dens on this level were full of whores, their pimps, their customers. The man had fallen on hard times; even down here most promoters had better accommodations, but the man and boy had been stuck in Whore’s Alley for months. Through one of the doorways, the boy spotted his friend Linna. But she was busy, a man’s hand resting on her thigh, so he didn’t wave hello.

“I hope you’ve got your best game today, Boy,” the man grunted. “Ellis brought that giant idiot of his, and he can swing a haymaker like no one’s business.”

The boy said nothing. He could already feel his blood warming up, drowning out the man, thrumming with the pulse of the ring. That was the thing about the ring: nothing mattered there. Not the man, not the hunger, not the dark warren-feeling of the tunnels. The ring was clean, well-defined. The ring was easy.

“Did you hear me, Boy?”

The boy nodded.

That was the thing about the ring: nothing mattered there. Not the man, not the hunger, not the dark warren-feeling of the tunnels. The ring was clean, well-defined. The ring was easy.

“Swear to Christ, half the time I think you’re a fucking idiot yourself. Speak when you’re spoken to!”

“I understand,” the boy intoned.

“Well, why don’t you say so?”

The boy shrugged. He had learned long ago that every time he opened his mouth, he gave a piece of himself away. Talking, particularly talking to the man, somehow lessened him. He was determined to give up as little as possible.

He had learned long ago that every time he opened his mouth, he gave a piece of himself away.

They climbed a poorly-carved stone staircase, reaching the second level. The boy could hear the low roar now, still several twists and turns away. But even though the sound was muted, it pulsed in his blood like alcohol, like morphia. He had been given morphia once, years ago, when his injuries had been so bad that he could not sleep or stay quiet. He had never forgotten that night…a long, snaking dream in his head, an epic journey through a world filled with light. It was seductive, the scale of that mindlessness, and for that very reason the boy distrusted it. He had never again tried morphia. The ring was not quite a narcotic, but its familiarity resonated in the boy’s bloodstream all the same.

“Have you stretched your arms?”

The boy nodded again, though he hadn’t. The man liked to brag to people that the boy was a physical marvel, and perhaps he was, for he never needed to stretch, never needed to condition, never needed to go through any of the hundred little routines that the other boys apparently did. He was always ready to fight.

“By the way, I thought of a name for you.”

I have a name, the boy almost said, then remained silent. The man knew he had a name; the man was the one who had tried to take it away.

“We’ll try it on tonight, see if it sticks.”

The boy nodded again, his silhouette bobbing its head on the wall beside him. He had suddenly realized, slightly panicked, that he could not remember his own last name. It had been years since he’d said it out loud, but he had always known it inside his head. His parents had given him his name, and even if they had been the worst parents imaginable – the boy suspected so – it seemed an important thing to keep, since he had been born with nothing else.

The roar had grown now, filling the tunnel, ringing off the stone walls to thrum inside the boy’s head. A good crowd, by the sound of it. That would please the man, but the boy hardly cared anymore. Even the people, their yelling and screaming, the smells they brought with them, tobacco and body-stink and cheap piss-watered ale, even these things didn’t matter once he was inside the ring.

They rounded the corner and the boy blinked into the blinding light. The room was blazing like a bonfire. Men surrounded him, some of them leaning forward to pound him on the shoulder. The man bared his brown teeth and bathed in their approval, shouting greetings to those he knew, as one would to friends, but the boy knew the truth: the man was nothing, and those who greeted him now cared nothing for him. It was the boy who was the prize, the thing of value, and the reason was simple: the boy never lost.

“Crush him, boy!”

“Kill that idiot!”

...the man was nothing, and those who greeted him now cared nothing for him. It was the boy who was the prize.

Peering through the crowd, the boy saw that it was indeed Brendan Maartens standing in the ring, his face white in the torchlight. The boy had heard about Maartens; at age fourteen, he was already approaching six foot and had arms like anvils. But he was also slow, and not just in speed. Maartens barely knew how to talk. The boy did not want to hurt an idiot… but he knew he would. Money was heavy in the air, the jingle and flash of coin. Mostly pounds, but the boy spotted Mort marks changing hands as well. The man pushed him forward through the crowd, and the boy tried not to wince as men slapped and punched him on the back. They meant it as approval, he supposed, but it was painful, particularly at the nape of his neck, where he’d been sucker-punched several weeks ago. The bruise had faded, but the pain had not.

“He’s so small!” a child’s voice piped up to the left. “How can he win?”

The boy spun toward the voice. Amid all the things in flux in this world, one fact held firm: he would win. It was the only thing the boy knew for certain, but it was enough; it had sustained him through the small wounds brought by each new day: the man’s drunks and his heavy hands; the knowledge that Linna, whom the boy thought he might love, was fucking men old enough to be her grandfather; and the blood of other boys, boys no older than himself, soaked into the skin of his knuckles. This certainty, the knowledge of his own abilities in the ring, was all he had. No brat could question it.

The voice had come from a dark-haired child, perhaps three years younger than the boy himself, with a narrow, pointed face. This child was well-dressed, in thick wool and a black cloak—he was from topside, clearly—but it was his eyes that caught the boy’s attention, bright green eyes that glowed in the lamplight. They were hungry, those eyes, and although this well-fed child couldn’t be more than eight years old, the boy sensed that he was unsatisfied, constantly seeking something he did not find. The boy wondered if he himself would look the same way if he ever got close to a mirror, if he could see himself for true. But he thought not. Somehow, the boy knew just what his own eyes would look like: filled not with hunger, but with vast distances of nothing.

“Back away, Tommy, or he’ll have you too!” a man shouted over the child’s head. This man was well-dressed also…a rich man, the boy thought, bringing his son down for a taste of the wild side. The boy turned to move forward toward the ring, but as he did so, the well-dressed man reached out a manicured hand and stroked the boy’s bottom. The boy halted, but then an iron grip descended on his shoulder.

“Do nothing!” the man hissed in his ear. “It’s the prince and his handler. This is a fight you can’t win, Boy. Get a move on.”

The boy went, raising his fists, dismissing the two of them from his mind. He was in the ring now, and in the ring there was only the opponent across from him, a white-faced idiot who, despite being more than a foot taller, would present no challenge at all. The boy could smell weakness, even well-hidden weakness, and he perceived that the huge man-child in front of him was frightened, too frightened to make full use of his enormous biceps, hopelessly cowed by a small, quick boy who was barely eleven years old.

The man had not followed him into the ring. He was still on the sidelines, downing several more shots of whiskey that had been offered his way. He gave the boy a quick grin, a comradely grin, as though they were a team. The boy closed his eyes, felt a wintry chill descend upon him.

“A perfect fighter!” the man shouted over the din, nodding this way and that, his face already gleaming from the whiskey. “Only eleven years old, and he cannot be beaten!” He waited a beat, until the crowd quieted down, and the boy felt an unwilling twinge of admiration; drunk or sober, the man was a solid showman. He always knew how to play the crowd.

“I give you…LAZARUS!”

Ignoring the howls of the crowd the boy waded in. A circle, quiet and cool, seemed to close around him, sealing him off from the world. Only when the opponent lay dead would there be anything else. The boy lashed out with his right fist and broke Maartens’s nose, watching as the taller boy toppled backward against the ropes. The boy had already forgotten everything: the man, Linna, even the well-dressed prince and his leering guardian. But the boy never really forgot anything, because six years later, when he stood before Thomas Raleigh in the throne room of the Keep, he would recognize those hungry green eyes with no trouble at all. The prince had aged, yes, but that was only chronology. Whatever he was seeking, it still eluded him.

He waited a beat, until the crowd quieted down, and the boy felt an unwilling twinge of admiration; drunk or sober, the man was a solid showman. He always knew how to play the crowd. “I give you…LAZARUS!”

But now there was only the ring, another fight that was over before really beginning, the baying of the crowd for a boy who never lost. Maartens had begun to cry now, but the boy was beyond noticing. Deep cold had descended upon him, for this was truly all there was; even at the age of eleven, he could already sense that there would be no life for him outside of this ring. There was a world up there, he knew, high above these stinking black tunnels, but it seemed to belong to someone else, and as Christian McAvoy—who would be known until the end of his days as Lazarus—lunged forward and began to kick his opponent to death, he never looked toward the world above, not even once.

Fate of the Tearling by Erika Johansen, $20, Amazon

Reprinted with permission from HarperCollins.