Life

The Craziest Cures For The Flu In History

It's flu season; have you stocked up on your garlic, horse manure, and teeth-pulling equipment? Cures for influenza, which has been responsible for some of the most gruesomely deadly epidemics in human history, have varied wildly across the centuries, but they definitely make contemporary vaccines and vitamin drinks pale in comparison. In retrospect, it's not really surprising; if you were faced with a deadly illness that apparently couldn't be cured, you'd resort to folk remedies and intensely strange magical potions as well, even if the results were likely not any better than just getting flu on its own.

Interestingly, our knowledge about influenza cures throughout history is significantly influenced by the fact that we're not entirely sure what the ancients knew about it. There's a strong chance it showed up in ancient Rome (particularly in animals), but it wasn't explicitly discussed in the texts of the time, and questions about exactly how it was regarded and treated persist up until the medieval period, where it's a candidate for the mysterious "sweating sickness" that caused huge deaths in Europe. It was the 1918 epidemic, though, that really got peoples' attention; according to statistics, 20 to 40 percent of the entire world's population became ill, and up to 50 million died.

These days, people are still afraid of swine and avian flu in their potential to wreak devastation of a similar kind. The Center for Disease Control estimates that the 2016-17 "flu season" is difficult to predict, but will likely last until the end of winter into spring, as usual. Thanks to the range of flu vaccines, what was once a scourge is now far less deadly. Here are seven of the strangest "cures" for the flu in history. Get ready to feel much more attached to your lozenges and honey-laden tea.

Ingesting Unicorn Horn

This is an interesting one: there's significant debate about what the English "sweating sickness" of the 13th and 14th centuries, which decimated huge proportions of the population, actually was. Arguments have been made for anthrax and hantavirus, but it's also been suggested that virulent influenza could be the culprit — and the potential cures available in medieval England were, shall we say, inventive. One collection of potential cures gives the option of "water of dragons" or "philosopher's egg," a delightful concoction made of an egg, saffron, mustard seed, and "ground unicorn horn." Where they got the unicorn horn is up for debate. (The disease even terrified royalty; Henry VIII apparently made his own "king's cure" of herbs and wine and tried to give it to everybody he knew.)

Wearing Necklaces Of Garlic

A lot of the remedies for influenza we've got in history appeared during the epidemic in the early 1900s, sweeping across Europe and into America. But one particular remedy is actually a lot older: the idea of garlic as an antiseptic agent. Apparently, during the American epidemic in 1917-18, people were inclined to wear necklaces of garlic while out in public, doing double service as both influenza-protection and a guard against vampires. (That wasn't part of the idea, but it should have been.) Interestingly, though, the idea of garlic as a cure for infectious diseases actually appears in ancient Egyptian medicine, with similar edicts: instead of wearing is as jewelry, one text recommends that those afraid of colds should wrap a peeled clove in muslin and pin it to the underwear. Sexy.

Using A Carbolic Smoke Ball

The carbolic smoke ball has the dubious honor of being one of the only flu remedies to have its own court case attached. It was created by Frederick Augustus Roe in 1889, and was advertised across England as a cure for influenza and basically any other illness to do with the nose and throat you could possibly imagine. The device was a rubber ball that, when squeezed, emitted a "puff" of carbolic acid which was designed to be inhaled and would apparently "flush out" dangerous materials from the sinuses and lungs.

As if this wasn't demented enough, the company published a famous advertisement saying that anybody who didn't find the cure efficacious would be awarded £100. The unfortunate Mrs. Louisa Elizabeth Carlill had bought the ball and used it well, but got the flu anyway (unsurprisingly), and the company refused to pay out. The matter went to court, and Mrs. Carlill won, with the judgement being that the advertisement made a contract with the public that the company had to honor.

Putting Eucalyptus Oil In The Rectum

The appearance of the carbolic acid ball wasn't even the strangest patent medicine available in England for influenza in the early 20th century. It was just the most famous. Because of poor laws regulating quack medicine, medical journals as respected as The Lancet ran ads for remedies in 1914 that Mark Honigsbaum, in his History Of The Great Influenza Pandemics, calls "outlandish". Old-school medieval tinctures like belladonna were on offer to the distinguished consumer, but surely the most embarrassing thing to inflict on a person warding off the flu had to be the recommendation that they regularly inject eucalyptus oil. Rectally. Yep.

Eating Pine Tar

Treatments for influenza in history were often meant to be preventive as well as curing; the idea was, for many of them, that you took them regularly to stave off the possibility of getting the disease. You can't really blame the populace; with no effective medical treatment in sight, they took to their own folk beliefs to try and keep themselves safe, even if the end result was likely more deadly than the disease.

The American epidemic of 1917 produced a large amount of folk remedies, some of which sound plain upsetting: Nancy Bristow, in American Pandemic, details everything from wormwood rubbed on chests to burning coal, but one of the most unpleasant has to be the idea of drinking "pine tar". That would be the combination of charcoal and pine used as a wood sealant on ships and to weatherproof rope. Drinking tar sounds decidedly more miserable and lethal than a dose of the flu, but what do I know.

Skinning A Sheep

This was a traditional method observed among the Boers in South Africa during the 19th century by the English, so it may need to be taken with a large dose of salt. But an apparently normal cure for influenza in tribal medicine in the area was to take a sheep or lamb, rapidly skin them, and then place the still-warm, bleeding skin on the chest of the sufferer. As far as practicality goes, this was likely very smelly and rather unpleasant, but doubtless it did actually keep the chest of the patient warm, which may have helped with their comfort. Poor sheep.

Surrounding Yourself With Horse Manure And Onions

A remarkable collection of folk remedies and superstitions from a county in Illinois, dating between 1890 and 1935, is a veritable treasure trove of down-home wisdom for dealing with sickness in areas where doctors were few and medicine was likely unreliable. It only has two possible solutions to influenza, one much less sociable than the other. The first suggests "placing onions about the patient's room" in the belief that the flu would actually "enter" the onion, which would then be thrown away. The second, though, involved carefully steaming horse manure and then spreading it on the poor patient's chest. There is no situation in which that person could have a sensible conversation with anybody.

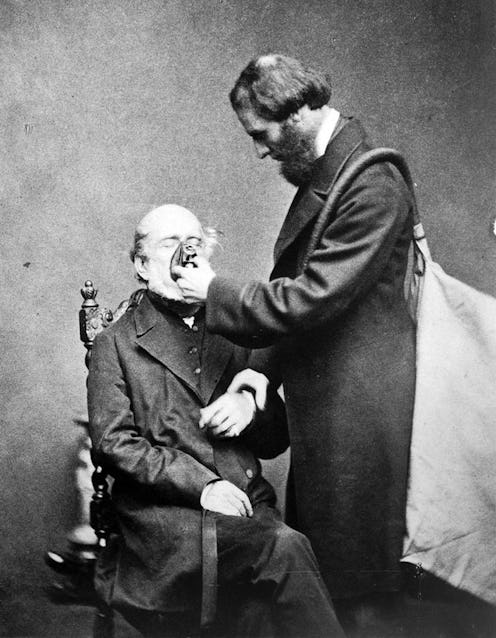

It wasn't just Illinois, though; the response to the 1917 epidemic in New York was also folk-remedy mad. People wore red rags tied to their arms and carried camphor balls around their necks, but some went further still. Stanford's biography of vaccine creator Jonas Salk includes the depressing detail that sufferers had teeth pulled, ingested strychnine and chloroform, and ate bizarre concoctions involving red peppers, none of which had any effect.

It wasn't until the discovery of a vaccine in the 1930s and widespread inoculation in the '40s that anybody felt they had any power over the rapid spread of the disease. Sure, getting the flu sucks, but least these days nobody's asking you to pull your teeth every winter.

Images: Taciuna Sanctitatis, Edward Minchen, Aberdeen Bestiary, Libris, Wellcome Images, Eveleen Myers/Wikimedia Commons