News

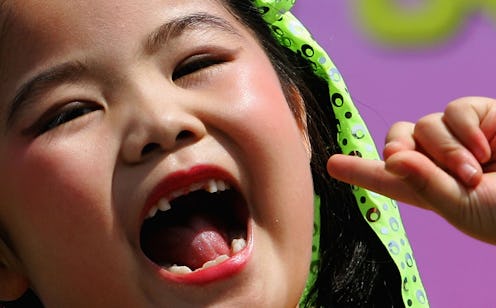

Your Sweet Tooth May Be An Evolutionary Advantage

Good news for sugar addicts and salty food fanatics: Having a sweet tooth — and a "salty" tooth — might put you at an evolutionary advantage. A study published in the journal PLOS linked childhood fondness for salty and sugary foods to greater growth spurts and more body fat percentage — growing taller was linked to having a "sweet tooth," and kids who craved salty foods often had more body fat. We'll be forwarding this to our parents, who hid the gummy bears and potato chips from us when we were younger. Parents: 0. Children: 1.

After participants were asked to taste and rate a number of soups, jellies, crackers, and sugar waters, researchers measured the dietary intake of the volunteer group. They also looked at other factors: Height, weight, body fat percentage, markers of bone growth, and TAS1R3 genotype — otherwise known as the genotype for the sweet taste, or "sweet tooth," receptor.

The results for the kids:

- Taller children tended to prefer sweet foods over salty foods, more so than shorter children.

- The children who preferred sweet foods also tended to show more "growth marker" in their urine.

- The children who preferred salty foods tended to have a higher body fat percentage.

And the results for the mothers:

- By and large, the mothers preferred much lower concentrations of salt and sugar than did children.

- Mothers who preferred sweet foods had a tendency to have the TAS1R3 genotype (something that researchers didn't find in children with sugary preferences.)

Because kids are constantly growing, it may be that childhood growth spurts are linked to an increased craving for sugar. It's also interesting that the tallest of the group were more inclined to want the sweet stuff.

The study was based on a small sample size: 103 children between the ages of five and 10, plus 76 mothers. (The study began with 108 children and 83 mothers, but a few were excluded because they didn't comply with study procedures or were ineligible). The study was conducted across two days by researchers from Philadelphia's Monell Chemical Sense Center.

As the study's lead author, Julie Mennella, told NPR, longitudinal studies are necessary to find out how growth is connected to sugary and salt preferences. (Remember, correlation doesn't equal causation). Recently, rates of childhood obesity have decreased, but we still gotta watch our calories and read our nutritional labels.