Life

5 Great Women Orators Hillary Should Channel

Hillary Clinton will shortly face one of the greatest tests of her rhetorical skills: her first Presidential Debate against Donald Trump at Hofstra University Monday night. It's a contest that will likely be won as much in confidence as it will in memorable, lengthy speeches; but it's important to remember that Clinton is part of a powerful American tradition of female speechmaking, in which rhetoric has been called upon to spread news, incite political action, and convince the populace of the evils of everything from slavery to child labor. Women have not been silent in the history of the United States; some of the most powerful speeches in the history of the country have come from female speakers. It's one aspect in which I'm sure Clinton would be proud not to be called unique.

While Clinton's own speech history is pretty starred (her "Women's Rights Are Human Rights" speech to the UN in 1995 as First Lady is rightly famous), people as diverse as Sojourner Truth and Mary Fisher have pushed the force of American speech forward over the centuries like typhoons. Whatever moved America's greatest women orators to speak, they did it with style and incredible power.

When Clinton takes the stage to debate Monday night, we hope she can channel them.

1. Maria W. Stewart

Stewart, as a 19th century lecturer and preacher, broke ground for African-American women across the country by speaking to mixed-race and mixed-gender audiences at public lectures. She was an intensely controversial figure whose attempts to galvanize action for African-American women to access education, and to spur structural change to allow the entire African-American community as a whole to attain wealth and power, often earned her uproar. Her speeches remain incredibly powerful, and one of the best-known (largely because Stewart herself recorded it and left copies for posterity) was one she gave in 1832 in Boston, in which she roared "Why sit ye here and die?" at her audience, and declared that free African-Americans were often no better off than slaves:

"Continual hard labor irritates our tempers and sours our dispositions; the whole system becomes worn out with toil and failure; nature herself becomes almost exhausted, and we care but little whether we live or die. It is true, that the free people of color throughout these United States are neither bought nor sold, nor under the lash of the cruel driver; many obtain a comfortable support; but few, if any, have an opportunity of becoming rich and independent; and the employments we most pursue are as unprofitable to us as the spider's web or the floating bubbles that vanish into air. As servants, we are respected; but let us presume to aspire any higher, our employer regards us no longer."

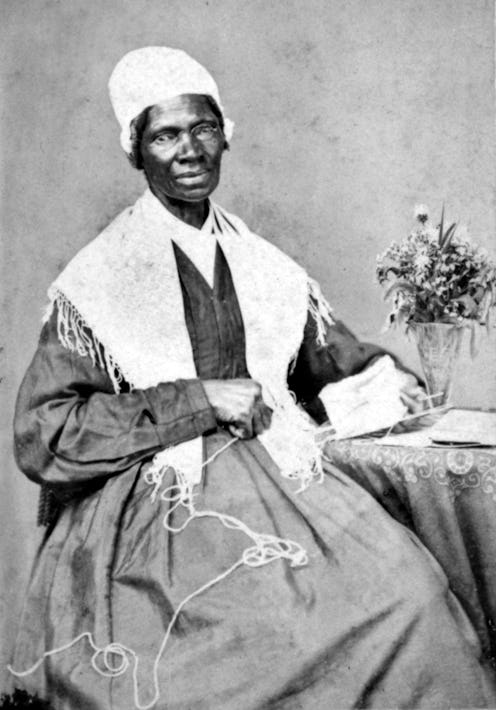

2. Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth, ex-slave and activist, made her name and entered the history books permanently with her off-the-cuff speech made in 1851 to the Ohio Woman's Rights Convention. The interesting thing about the speech, now known as "Ain't I A Woman?", is that the version that we study as a rhetorical masterpiece may actually not be completely accurate. The original, as a curator of the National Digital Newspaper Program of the Library of Congress points out, wasn't transcribed; it was described in the New York Daily Tribune, and none of the rhetorical flourishes that later became famous (the phrase "I am a woman's rights," and the question "ain't I a woman?") appear at all. The version with which we're now familiar appears to have been concocted from both sources and fantasy by women's rights activist Frances Gage when she published a "transcription" in 1963. But the basics, which rage against the depiction of female weakness and point out the necessity of women in the Bible, remain essentially the same.

"That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman?"

3. Anna Howard Shaw

The great names of the suffrage campaign in American history are well known: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, the list goes on. All were powerful rhetoricians; but one stood out from them all, and has contributed one of the greatest speeches in the history of American letters, unprecedented both in its scope and its aims. It was made by Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, the first female Methodist minister, in her last year as President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1915, as the horrors of the First World War filled the news.

The speech, "The Fundamental Principles Of A Republic," roots the pursuit of suffrage at the very beginning of modern American history, traces it through the Puritans to Jefferson through to the 1910s, and gives accounts of all the arguments against it that she's encountered throughout the country, from women and men alike. (It's also, importantly, very funny and very sad.) It's a piece of history as much as it is a piece of astonishing speechmaking; the foundation of the American Republic is freedom, and she demands that the vote be the freedom that women deserve:

"If woman's suffrage is wrong, it is a great wrong; if it is right, it is a profound and fundamental principle, and we all know, if we know what a Republic is, that it is the fundamental principle upon which a Republic must rise...

If we trace our history back we will find that from the very dawn of our existence as a people, men have been imbued with a spirit and a vision more lofty than they have been able to live; they have been led by visions of the sublimest truth, both in regard to religion and in regard to government that ever inspired the souls of men from the time the Puritans left the old world to come to this country, led by the Divine ideal which is the sublimest and the supremest ideal in religious freedom which men have ever known, the theory that a man has a right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, without the intervention of any other man or any other group of men. And it was this theory, this vision of the right of the human soul which led men first to the shores of this country."

4. Barbara Jordan

Jordan was a person of firsts in many ways: the first African American member of Congress to hail from the American South, she made a name for herself as one of the greatest speakers of the 1970s. Her most famous speech was her keynote address to the 1976 Democratic Convention (another first, as the first African American woman to do so), in which she galvanized the party to return to its fundamental principles: "equality for all and privileges for none." It's a speech that, in its call for unity around American principles instead of divisive politics, creates an acute contrast to today's political landscape.

One of the most famous parts of the speech depicted the American people as looking for answers:

"We are a people in a quandary about the present. We are a people in search of our future. We are a people in search of a national community. We are a people trying not only to solve the problems of the present, unemployment, inflation, but we are attempting on a larger scale to fulfill the promise of America. We are attempting to fulfill our national purpose, to create and sustain a society in which all of us are equal."

The Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs comments, "Where are our Barbara Jordans? As we feel the painful separation of increasingly bipartisan politics, there is a yearning for those days of inclusiveness."

5. Mary Fisher

The HIV-positive AIDS activist Mary Fisher is credited with breaking one of the biggest misconceptions of the 20th century: that AIDS was exclusively something that happened to gay men. Standing at the Republican Convention in 1992, met with what ABC News called "stunned silence," she explained that though she had contracted the disease from her husband, she was "one with the lonely gay man" and "a black infant struggling with tubes in a Philadelphia hospital." As the archetype of modern American respectability — blonde, beautiful and the daughter of a Republican adviser — she told the assembled Republicans that compassion and understanding should prove superior to shame, and that urgency meant that nobody could afford to turn a blind eye to a gigantic health crisis engulfing the nation. Norman Mailer reported at the time that "the floor was in tears, and conceivably the nation as well," and when you read the speech you well understand why:

"This is not a distant threat. It is a present danger. The rate of infection is increasing fastest among women and children. Largely unknown a decade ago, AIDS is the third leading killer of young adult Americans today. But it won’t be third for long, because unlike other diseases, this one travels. Adolescents don’t give each other cancer or heart disease because they believe they are in love, but HIV is different; and we have helped it along. We have killed each other with our ignorance, our prejudice, and our silence. We may take refuge in our stereotypes, but we cannot hide there long, because HIV asks only one thing of those it attacks. Are you human? And this is the right question. Are you human? Because people with HIV have not entered some alien state of being. They are human."

While orating isn't necessarily known as Clinton's main strength, she will certainly be channeling a long line of women when she takes the stage Monday night to make some history of her own.

Images: Smithsonian, Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons