News

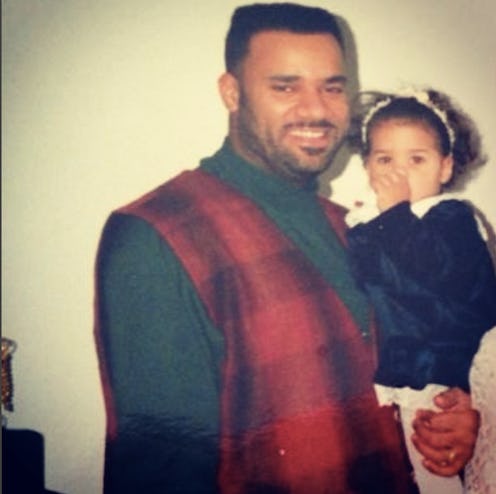

I Think Of My Dad Whenever Police Kill A Black Man

It seems like every other day, I'm confronted with the weight of my black body, as I see another Twitter hashtag remembering yet another black person who was murdered by a police officer. It never gets easier to deal with, likely because I've had too little time to process the previous shooting before the next one happens — like when Philando Castile and Alton Sterling were both killed by police officers within a span of 48 hours. But no matter which name becomes a hashtag in these instances, I think of my dad every time an unarmed black man is shot by police.

Terence Crutcher, a father of four, was lethally shot by a Tulsa police officer on Sept. 16. Crutcher's car had issues as he drove home from his community college classes, and he needed assistance to get it running again. After following police orders and walking back to his car with his hands in the air, a Tulsa police officer tasered him before another shot him dead.

Police have shot 162 black men in 2016 alone. Although this makes Crutcher's situation unnervingly common, it doesn't make it any less horrifying when I think of how my dad could easily be the next.

My dad is a 6' 3'' man who is actually half white, but that doesn't matter, because to a police officer, he is black. To the Tulsa helicopter pilot who narrated the harrowing video of Crutcher's death, he would "look like he's a bad guy" because he is black. He carries the weight of that, and faces the same fate as any other black man in our country, simply because his skin is more brown than that of the police officers he's encountered throughout his life.

Maybe I think of my dad because I'm reminded of a story about when he was pulled over by a police officer for no apparent reason. He was driving a new car in our mostly-white neighborhood in the suburbs of Chicago, when an unmarked car flashed its lights and pulled him over. He was accompanied by my mom, who is white, and was accosted by a plainclothes police officer, who not only could not give a reason for pulling him over, but also demanded that my dad show a bill of sale for his car and explain to the officer who my mom was and why she was riding with him. Meanwhile, this officer refused to give my parents any information identifying himself, and later threatened to take my dad to jail for reasons that remain unknown today.

Whenever I ask my parents to reflect on that story, they both mention how "lucky" they feel that it didn't escalate to something worse. "I would be scared for dad's life if he got pulled over today. He knows to follow the police's orders and not say anything, but I don't think that would be enough anymore," my mom tells me. And I feel that same fear every time I hear another story of police killing an unarmed black man.

I feel "lucky" that my dad hasn't been wrongfully pulled over by police too many times throughout his life, especially in recent years. But I've spent 23 years listening to the racist comments people make about him, and in light of these shootings, I've realized that this could happen to anyone. During trips to the grocery store, I've heard white cashiers assume out loud that we "must have just received food stamps," given the amount of groceries we were buying for our family of five. Other kids' parents at school would tell my mom that "there's a difference between a black person and a n*gger" and that, "lucky" for her, my dad, my siblings, and myself are not the latter.

But the reality that this could happen to anyone is something people, particularly those who aren't black, fail to recognize whenever there's a police-involved murder. The generalizations are deep-rooted in the way people talk about us, and especially in the way they justify these shootings.

I wouldn't have the strength to carry on if my dad were senselessly murdered by a police officer. I would fail to uphold the image of a strong black woman who feels forced to appear unfazed by these all-too-common killings of black people. There is a clear, inherent danger ascribed to the black body — not just by police officers, but by prejudiced parents, cashiers, friends, and strangers.

My dad inhabits one of those black bodies, and until he doesn't (which is impossible), I'll always worry about him whenever I'm trying to make sense of yet another nonsensical police murder of a fellow black body.

Images: Alexi McCammond/Bustle (1)