Life

7 Moments In The History Of International Feminism

How much feminist history did you learn at school? Hopefully you were introduced to Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Mary Wollstonecraft, and you were probably drilled in the dates universal suffrage became legal. But what about feminists in other countries? As today's feminists continue to attempt to make the movement more intersectional, acknowledging the competing discriminations of class, race and economics, and more inclusive (i.e. not just for rich white girls), it's become even more crucial to understand that there is a joint, international feminist history worldwide. These different activists may not have met up for tea, and would likely have disagreed on certain issues, but these women agitated for the rights of their gender and deserve to be more widely known.

It's a legitimate question as to whether we can call women's rights activists "feminists" in countries where the movement itself wasn't necessarily known. As we'll see, different countries have their own complicated, cultural ideas about women, class, and rights, a diversity that's an essential part of their own journey towards gender equality. I've used the term as shorthand here to indicate women and organizations who've targeted some of the most obvious parts of feminist thought (women's right to education, the vote, political participation, and economic emancipation), and have been referred to as feminists by other people in their own country.

From Sierra Leonean founders of girls' schools to Chinese anarchist writers, here are seven moments in the history of international feminism that you definitely need to know as part of a well-rounded feminist education.

1878: The Bestuzhev Courses Open Higher Education To All Russian Women

In the wake of Pussy Riot's imprisonment, it can be easy to forget that Russia has a brilliant history of women's activism and rights, and one of its most splendid moments was the founding of the Petersburg Higher Women's Courses in 1878. Before this point, women had been almost universally barred from university courses across Russia, but the Bestuzhev Courses, as they became known (the first course director was the famous Russian historian Konstantin Bestuzhev-Ryumin), were a huge shift: they were open to women of all social classes, and after an initial focus on the liberal arts, gradually expanded the curriculum to include science and mathematics. In the college's first eight years, it enrolled 700 students; but it wasn't an unclouded victory. The women had to study at night, and the educational establishment of the time refused to give them recognized degrees at the end of a course of study.

1882: Tarabai Shinde Publishes "A Comparison Between Women and Men" In India

Feminist essays have, in the history of fights of the rights of women, been incredibly influential, with lasting aftershocks across the political spectrum. In the pantheon of world-changing feminist publications, though, social activist Tarabai Shinde's "Stri Purush Tulana" (which translates as "A Comparison Between Women And Men") in 19th century India ranks as one of the most important. Shinde, outraged by the influence of patriarchy on women across India, regardless of caste, published the 52-page essay to highlight "the way in which it was always women who got blamed for every kind of evil and suffering in Indian society." Among other points, the furious essay maintained that all the negative qualities attributed to women, like suspicion and treachery, were actually more prevalent in men. The work was so controversial that it was essentially suppressed until the mid-1970s.

1907: He Zhen Shocks China With "On The Question Of Women's Liberation"

He Zhen is a complicated historical figure; her feminism was based on a firm belief in anarchism, which, some scholars have argued, expanded the fight for Chinese women's rights from nationalistic politics to social revolution. He Zhen (her assumed name for publication, meaning "Thunderclap") is now most famous for her 1907 essay "On The Question Of Women's Liberation," in which she essentially argued that women deserved equality and couldn't get it until they were economically self-sufficient rather than dependent.

The essay itself is an astonishing one. "For thousands of years," it begins, "the world has been dominated by the rule of man. This rule is marked by class distinctions over which men—and men only—exert proprietary rights. To rectify the wrongs, we must first abolish the rule of men and introduce equality among human beings, which means that the world must belong equally to men and to women. The goal of equality cannot be achieved except through women’s liberation... I address myself to the women of my country: has it occurred to you that men are our archenemy? Are you aware that men have subjugated us for thousands of years?"

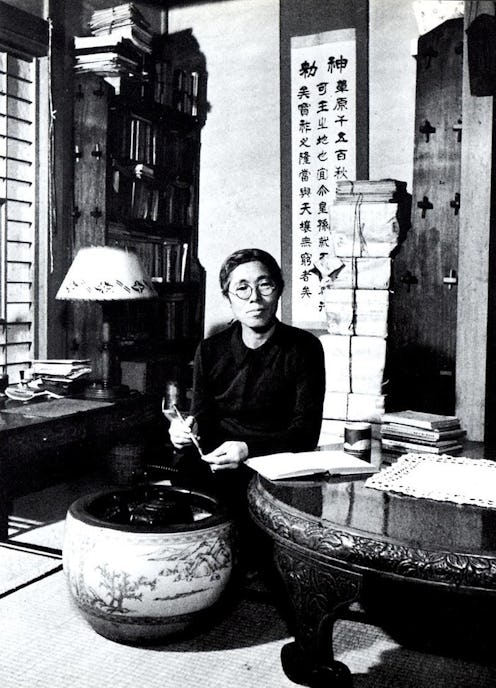

1920: The New Woman Association Fights For Female Participation In Japanese Politics

One of the early concerns of Japanese feminists in the 20th century was the right for women to participate in politics, from voting to running for office or involving themselves in any other part of the process (all of which was against Japanese law). The pioneering feminists Fusae Ichikawa (pictured), Oku Mumeo, and Hiratsuka Raicho, who'd had enough of this state of affairs, founded the Shin Fujin Kyōkai (New Woman Association) in 1920 to agitate for the power for women in politics. The party was among several that pushed for women's rights in Japan at the time, though it made an impact through the fact that Mumeo carried her newborn son around in a pram while handing out pamphlets. Their big focus was the Peace Preservation Law, which explicitly prevented women's political participation, and they saw a victory in 1922 when the Japanese Diet passed a law allowing women to join political parties for the first time.

1921: The Bangiya Nari Samaj Fights For Women's Suffrage In Bengal

Women's suffrage was often the central case of 20th century feminist organizations worldwide, and Bengali India was no exception. Founded in 1921 by activists Kumudini Mitra, Kamini Roy (pictured) and Mrinalini Sen, the Bangiya Nari Samaj was aimed explicitly at getting women the vote. It wasn't initially successful; a new law about women's suffrage was defeated in 1921. But by 1925, the mood had sufficiently changed that the Bengali government allowed women's suffrage for the first time. One of the founders, Roy, gave further fuel to the fire of feminism burning in early 20th century India by writing extensively on the need for women's education.

1932: Adelaide Casely-Hayford Opens The Girls' Vocational School In Sierra Leone

There's an entire school of prominent African feminists in history, but it's Adelaide Casely-Hayford, the Sierra Leonean activist and feminist, who marks one of the earliest movements towards women's rights. She's not an uncomplicated woman by the standards of modern feminism; she's commonly referred to as the "Victorian feminist," because her vision of girls' education, which led to her founding of the Girls' Vocational School in 1932, was focused on domestic skills rather than maths or literacy. However, the aim of the curriculum, which emphasized traditional African art as well as practical skills like baking, was partially intended to allow women to make a living if they needed to be financially independent. Along with Charlotte Maxeke, who founded the Bantu Women's League in South Africa in 1918 to protest against an apartheid policy that non-white women needed to carry passes, she's one of the earliest figures in African feminism.

Images: Library Of Russia, LibCom, Shigeru Tamura, Ragib, Ma Mashado/Wikimedia Commons