Books

Why Hemingway's Short Stories Made Me So Angry

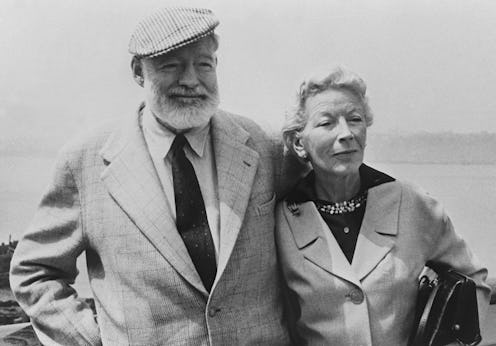

As I read the pages of Ernest Hemingway's T he Snows of Kilimanjaro & Other Stories for the first time, I quickly realized something about his writing: his pattern of sexism, misogyny made it impossible to take his stories seriously. I had to stop reading on multiple occasions to remind myself that this was written in a completely different time; I had to remind myself that Hemingway was 21 years old when women first got the right to vote. But is that really an excuse?

My opinion on this is plain and simple: Ernest Hemingway's approach to female characters was problematic, to say the least. I've seen evidence of this attitude over and over again in Hemingway's literature: in The Sun Also Rises with the "damned good-looking" Lady Brett Ashley; in To Have and To Have Not with the female characters who are nothing more than plot devices used to further the stories of their husbands; in Hills Like White Elephants with the woman who can't order a beer without a man's help.

There are two types of women in Hemingway's pieces: the women who are weak and subordinate to men and the women who are seductive and over-sexualized. In the short story collection The Snows of Kilimanjaro, I saw both these characters.

In the titular story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” the main female character, Helen, takes care of her dying husband, Henry, as he drinks and insults her the entire time. He calls her a bitch on more than one occasion. He blames her for taking him away from his talent — writing:

"You bitch," he said. "You rich bitch. That's poetry. I'm full of poetry now. Rot and poetry. Rotten poetry."

She doesn’t stand up for herself. Not once. She allows him to berate her as she continues to serve him.

Then on the other end of the spectrum in “The Short Happy Life of Frances McComber,” there's Margot McComber who — drum roll, please — is the antagonist of the story. She is the opposite of Helen; she does whatever she wants. She is clever and beautiful and forms opinions based on her feelings in the moment. When she and her husband, Francis, travel to Africa on a hunting trip, tensions within their marriage come to a breaking point, especially after Francis proves himself to be a coward by running from a lion:

"Did you shoot it, Francis? [Margot] asked." This is her mimicking him for his lack of aim on the safari outing gone terribly wrong. The one where he shoots a lion just shy of the head, injuring and not killing it, putting everyone in danger, and then running away without finishing the job.

"Yes."

"They are dangerous, aren't they?" Margot again mimicking him on his cowardice.

"Only if they fall on you," Wilson told her.

'I'm so glad." Straight sarcasm.

"Why not let up on the bitchery just a little, Margot."

"I suppose I should since you put it so prettily."

Margot is the queen of sass. She has a voice, and she isn't afraid to use it — unlike Helen. But Hemingway doesn't mean for this to come off as empowering. Not at all. Rather, Margot's outspoken nature is a detriment to her character and the people around her, namely her husband, Francis.

Near climax of the story, the plot flips in favor of Francis McComber. He redeems himself and kills a water buffalo. But his wife doesn't think any less cowardly:

"Francis Macomber felt a wild unreasonable happiness that he had never known before.

'By God that was a chase, he said. I've never felt any such feeling. Wasn't it marvelous, Margot.'

'I hated it.'

'Why?'

'I hated it,' she said bitterly. 'I loathed it.'"

Margot couldn't be happy for her husband; oh no, that's not the type of woman Hemingway wrote. She is a strong woman, so she is characterized as the villain. As the jealous betrayer and (spoiler) eventual murderer of her husband. She has no redeeming qualities, and the reader is not encouraged to sympathize with her or relate to her in any way.

It may not seem like a big deal in the grand scheme of things, but it is. There’s no denying that Ernest Hemingway was a genius. His work is exceptional in many ways. But we cannot discuss his legacy without discussing his problem writing women. Because here's the thing: strong women make the world turn; soon, a strong woman may be the most powerful person in the world. Hemingway — and all authors — must write their female characters with nuance, with sympathy. Because women aren't villains by virtue of being strong.