Style

7 Bizarre Beliefs About Nails From History

These days, the most attention your nails are likely to get has to do with the relative ridiculousness of your nail art tastes. (3D manicures? 100-layer nail polish? What on earth is everybody doing to themselves?) But nails have carried political, social, medical, martial and mythic significance within various civilizations for centuries; as far as their aesthetic importance goes, we modern-day nail artisans are amateurs. Like anything that could be adorned, they've been part of demonstrations of wealth and power over the millennia, but their significance has gone deeper. We're not only interested in the living nail, as it turns out; as far as human history goes, we invest it with a lot of significance after its holder is dead. And that's just the start.

Using the history of nails as a lens to examine history itself might feel a bit silly, and on one level it is; but how people choose to interpret, use and decorate their bodies isn't just a vanity thing. One look at the nails of royals of the Zhou dynasty and you'd see their class status, while nails created a distinct social signal in the Netherlands of the 17th century that would be almost untranslatable to outsiders. That's not to say some of the history of the nail hasn't just been plain disgusting (a boat made entirely out of ghostly toenails, anybody?); but the nail has played a far more important cultural role than you may imagine.

Here are seven of the most bonkers beliefs about nails in the history of the human cuticle. Remember your gold manicure kit the next time you're fighting an ancient Sumerian army.

1. They Are Made Of Dried Up Muscles

Knowledge of the actual composition of nails is now commonplace: many of us know they're made of keratin, the same material that makes up our hair. (Keratin science is still in its youth, though; we only sequenced the DNA of the substance for the first time in 1982.) But the material that makes up the "horny zone" of the nail (yes, that is the actual, medical term for the hard surface that's visible at the ends of your fingers and toes) has been historically debated. Ancient Greek writer Pliny the Elder, who never met a part of anatomy of human behavior that he didn't have an opinion on, explained that it was "generally thought" in his lifetime that nails were "the termination of the sinews;" in other words, the ligaments of the hands and feet protruded through the skin and hardened into horn-like surfaces. It's not the silliest idea in the world.

2. Soldiers Need Manicures

This one's fascinating, though we're not entirely sure if it's correct. An archaeological dig in the 1920s and '30s in the ancient city of Ur, which flourished as part of ancient Babylon around 3,000 years ago, found what the researchers believed to be a solid gold manicure kit. The real newsworthiness of the find, particularly for observers of the period, was the fact that the kit appeared inside royal tombs, as well as in those of warriors. It seems that manicures with kohl may have been part of battle-readiness for Babylonian warriors of high status, possibly for intimidation or ritual purposes.

3. The End Of The World Involves A Boat Made Out Of The Fingernails Of The Dead

As far as mythological vessels go, this one wins the prize for most disgusting: in ancient Norse mythology, Naglfar is one of the key signals of the apocalypse (or Ragnarok, as it's called) — it's a ship that ferries the spirits of dead warriors towards the final battle with the gods. And, with worrying implications for its seaworthiness, it's apparently made up of the nails of the dead, to the extent that Snorri Sturluson, who wrote the Edda, an 11th-century compilation of Norse myth, warned that warriors should probably have their nails pared, as "if men die with uncut nails" they'll just contribute material to the vast ship. It's not clear whether nails are the actual make-up of the vessel, or if it's a strange mistranslation from old Norse; but I personally prefer the more visceral interpretation.

4. They Are A (Potentially Lethal) Sign Of Your Royal Status

Nobody knew more about using nails to show off than the ancient Chinese. They were among the first to produce nail polishes out of egg whites, beeswax and other materials (they were usually very sticky and without a quick-dry facility); and the colors changed with the fashion, to denote royal status with every successive dynasty. The Zhou dynasty, around 600 BC, won for style, as the royal family reportedly had nails painted with gold and silver dust. But this wasn't their only contribution to the idea of nails as obvious symbols of status; they also perfected the thoroughly threatening nail guard, an item of fashion in which both men and women wore long (up to 6-inch) pointed, gilded "tips" on their elongated nails.

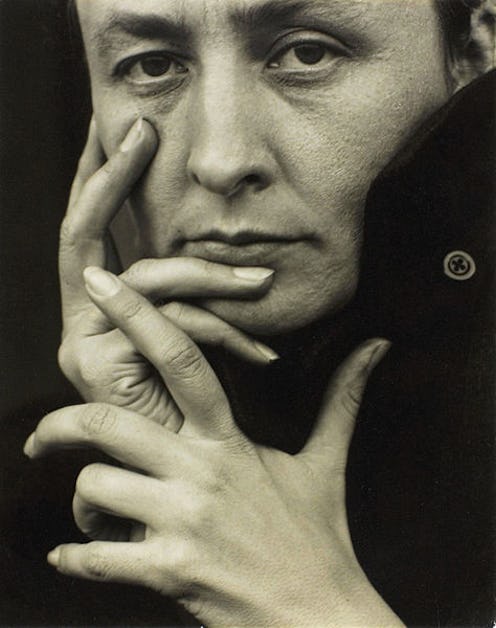

One of the most powerful women in history, China's Empress Dowager Cixi, was photographed in 1903 in court with phenomenal spiked nail guards; the point wasn't just to look like an animal, but to emphasise that she'd never had to do a day's labour in her life, and could afford for her hands to be essentially useless. Interestingly, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford has "night" protectors for nails, made of wood; you'd cap them on your long nails at night and wear your more ornate versions during the day. And yes, they were worn by both men and women, and were made with materials ranging from tortoiseshell to precious stones.

5. They Are The Best Way To Demand A Drink

If you've spent any time around portraits from the Netherlands in the 17th century, you may have noticed a peculiar trope: a person turning towards the artist while attempting to empty a cup onto their fingernail. It turns out that "the fingernail test" was a common way to gesture for a drink during that period: you'd catch a bar worker's eye and tip up your empty cup above a single nail, attempting to collect even a droplet of fluid on its surface. Pretty obnoxious, but it turns up in a bunch of paintings from the period, usually of young hearty-looking men who seem like they probably didn't care about being thrown out of bars for being rude.

6. You Can Heal A Broken Toenail With Hemp

One of the most fascinating episodes in the history of nails is centered on something entirely separate from the health of our "horny zones": it's a key part in the history of human cannabis use. The ancient Egyptians, it turns out, thought that hemp could be a vital medicinal material when it came to fixing broken or hurt toenails; both the Ebers Papyrus, from about 1550 BC, and the Hearst Medical Papyrus, from about 2000 BC, contain the same method for healing an unnamed toenail problem: hemp. Supposedly, wrapping it in a bandage with a mix of honey, ochre, hemp and other plants would make everything better. It's one of the first records of hemp being used in any way in human history, and it was attributed to the humble toenail, likely after it had been stubbed on an ancient Egyptian table.

7. It's A Good Idea To Sell The Nail Clippings Of Dead Saints

If you've spent any time in the holy sites of Christianity, you'll know that relics and their holders, called reliquaries, are a big deal. Kings, popes, churches and noble families of all kinds would pay huge sums for an item from the body of a saint, or anything related to Jesus; it's an old joke that there must be enough "fragments of the True Cross" around to make up an entire forest. (This wasn't really the fault of the churches; the Second Council of Nicea proclaimed that every consecrated altar in the faith had to have a relic of some kind, which remains the case in some parts of Christianity).

But things got weirder when abbeys or monasteries were actually in possession of the body of a saint, particularly if they were only recently deceased. A 2011 exhibition at the British Museum pointed out that the faithful would actually open the tomb and trim the nails of the deceased — technically to clean them up for God, but mostly for the value of selling the relics. These days, you can see the nail clippings of St. Clare in Assisi; they're probably the most famous ancient holy nails around.

Images: L.M. King, Alfred Stielitz, Charles Monnet, Johannes Gehrts, Yu Xunling, Frans Hals, Internet Book Archive Images, Vassil/Wikimedia Commons