Life

Ever Been In an Insomnia Competition?

As I write this, I'm deep in the throes of a bout of insomnia. They're cyclical for me: two or three weeks of light, relatively normal sleep — followed by a week of not being able to fall or stay asleep at all. It's a less-than-fun existence, and everyone with whom I've ever shared a room, from babyhood on, can testify to my seemingly never-ending quest for a good night's sleep. Until college, I never thought of it as something to brag about.

Sleep, it seemed, was discouraged the moment I moved into the dorms at Princeton. My very first week, a group of Red Bull marketers left a four-pack of the energy drink at the door of the suite I shared with three other girls. With it was a preprinted note exhorting us to make the most of our time at Princeton — by using Red Bull to stay awake for all four years, presumably.

More than once I was told that having insomnia was probably pretty great, since it meant I could stay up late writing papers without issue. In these people's minds, my lifelong complaint became a superpower.

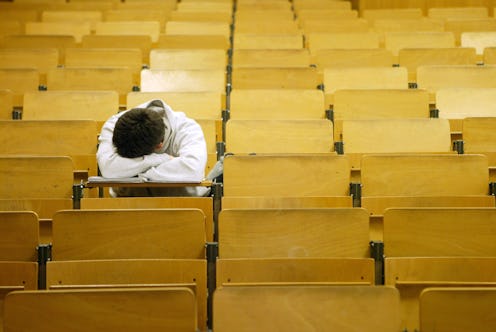

We did stay awake the bulk of those first few weeks, through orientation, and backyard parties, and into the first week of classes. Slowly, the excitement wore off — but the sleeplessness kept going. I began hearing the same axiom uttered over and over again from all corners: "Sleep, grades, social life: pick two." Consensus on which two should be prioritized was clear: we could sleep when we were dead (or graduated).

Encouraging a Problem

Initially, it felt like I fit right in. Everyone else was choosing not to sleep, so my oft complete inability to do so seemed, for the first time in my life, like a good thing. It's still the strangest sense of self-confidence I've ever felt: I could stay awake studying and socializing with the best of them simply because my body didn't allow me to do otherwise.

By midterms, though, I began noticing unusual behaviors among my classmates that I had brushed off before. In high school, whenever I mentioned how little sleep I get, I was always met with sympathy and the same litany of advice. But in college, every time I lamented not having fallen asleep until 4:00 a.m. I was one-upped by someone who had stayed up until 5:00 working on a paper.

It wasn't an overt competition; seeing someone run around campus gleefully shouting about how little sleep they got the night before would still raise more than a few eyebrows. But these displays of nocturnal superiority were couched more in a discussion of whose life sucked more. It was just a polite way of arguing about the most self-esteem-destroying aspect of any competitive college student's life: who was willing to give up more for success.

"Sometimes I Wish I Had Insomnia"

The problem for me was that I wasn't willingly forgoing sleep. In fact, I coveted it. Unlike many of my friends with intermittent sleep issues, I've never been able to link mine to anything, be it weird food, menstrual cycles, or plain-old stress. I can't just take better care of myself to make it go away — nor, when total exhaustion comes hurtling at me, can I resist the pull of a decent night's sleep or a much-needed nap.

Princeton, like many a competitive school, is a go-go-go kind of place. Despite campus efforts to raise mental-health awareness and encourage healthy work habits, the population tends to stick to the tried-and-true approach of many consecutive hours of intense study followed by a few of sleep. It's broken up occasionally by late-night weekend parties.

More than once I was told that having insomnia was probably pretty great, since it meant I could stay up late writing papers without issue. In these people's minds, my lifelong complaint became a superpower.

I began to wonder: should I take advantage of my problem? Instead of lying in bed bored and waiting for sleep to come, or reading a book under the covers until I couldn't keep my eyes open anymore, should I have been using that unwilled consciousness in a way my peers deemed more productive?

A Widespread Issue

At my alma mater, 58 percent of students report feeling well rested only three or fewer days per week. When a majority of students report feeling that tired, it's not just an isolated problem: it's a culture issue. And pressure not to sleep isn't a phenomenon restricted to Princeton, or even Ivy League schools more generally: It's estimated that college students throughout the United States average only about six hours of sleep per night.

By my senior year, I had settled in somewhat, even as things around me stayed the same. I still felt painfully self-conscious when I occasionally passed out from exhaustion by midnight, or took an afternoon nap. But by then I'd also forged close friendships with another insomniac, my one-woman sleep-encouragement support group.

One day, near the end of the year, I came across some friends a year below me complaining (and one-upping each other) about the independent research required of most juniors. They asked me how I got through it, and I answered honestly: by learning to prioritize my mental health; stopping when my body and mind needed me to; and by getting as much sleep as I could, even if it wasn't as much as I needed.

They all looked up at me in wonder. "Wow. You're so ... healthy," one replied, not a hint of irony on her face. And then they went right back to their continued lament, as though such options were completely unattainable.