Books

7 Common Phrases With Surprisingly Morbid Origins

My second novel, The Last Confession of Thomas Hawkins , begins with a trip to the gallows. Tom Hawkins — who protests his innocence — is about to hang for murder.

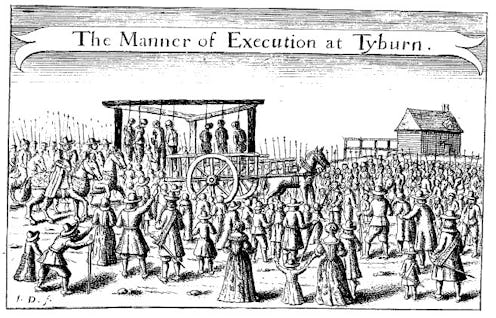

It will take at least two hours through the crowds and into Tyburn, a village that became the principal place for the execution of criminals in England. My novel is set in London, 1728, when executions were public holidays. Tens of thousands of spectators would spill out into the streets to watch the condemned ride to the gallows on carts swagged in black crepe. Parents would lift their children on their shoulders for a better view. Meanwhile the prisoners were forced to ride backwards, wrapped in the rope that would hang them, their coffins digging into their backs at every lurch forward.

Hanging days were such public and pivotal events, that numerous slang words and phrases were born from them. London crowds were notoriously subversive (and generally drunk). No surprise, then, that they turned what was supposed to be a moral lesson into a raucous festival, filled with its own irreverent language.

What’s more surprising is how some of these phrases have passed into general use. Here are some familiar expressions that either originated on the road to Tyburn, where the hangings occurred, or are linked to it:

1. "One for the road."

As the carts rolled from Newgate prison to Tyburn, they would stop at taverns along the route, allowing condemned prisoners one last drink (or two). Thus starting the tradition of "one for the road" — in practice usually meaning several for the road.

2. "You’re pulling my leg."

In the early eighteenth century there was no quick "drop" at the scaffold, as it had not yet been invented. Prisoners suffocated slowly on the rope; it could take up to twenty minutes to die, and must have been agonizing. Sometimes spectators would take pity and pull on the victim’s legs to help speed things along. How this phrase transformed into its modern meaning is a little unclear. Most likely it’s akin to the phrase "you’re killing me" — a protest against being teased or wronged, in other words.

3. "A leap in the dark."

While this term wasn’t invented at Tyburn, it was certainly popularized there. The hangman would roll a hood over the prisoner’s face just before the cart pulled away. It was probably better than facing a hundred thousand cheering spectators. And they were certainly jumping into the unknown, as the expression now suggests.

4. "Falling off the wagon."

Another reference to that final tavern break. As prisoners got "back on the wagon," they knew they would never drink again. (I should add that I’ve read a different theory about the provenance of this phrase, but this one seems the most likely to me — and also predates the other meaning.)

5. "Well hung."

Much disputed, this one! But I include it for your consideration. Being slowly asphyxiated had certain effects on most male prisoners. (As if voiding your bowels in front of the whole town wasn’t dispiriting enough.) Put simply, many got an erection, and often ejaculated. So the theory is that to be "well hung" originated from that "venereal event," as they might have put it in the eighteenth-century. There’s a more straightforward explanation for the phrase, but don’t tell me you didn’t learn something here.

6. "To go west."

Again, while this term was in use elsewhere, it was popularized around this time. The route from Newgate gaol to Tyburn was westerly. So "to go west" meant "to go to your death/to die" — a phrase still in use today.

7. "Left in the lurch."

Also somewhat disputed, but this one feels convincing. A "lurch" was another term for the cart or wagon used to convey the prisoners to Tyburn. Sometimes a prisoner would be left in the cart while the constables went off for a drink. So to be "left in the lurch" came to mean being abandoned.

The precise origins of old phrases are notoriously difficult to pin down. (My references for the above come from both contemporary sources and modern histories.) What seems to connect all these expressions is an irreverence and sang froid in the face of death. To have "a good dying" — to go to your death with poise, courage and a flash of wit — was the finest compliment the London crowds could give a convict.

Images: Wikimedia Commons (7)