Books

The 11th Century Inventor of the Listicle

If you’ve ever been to the Internet, you’ve probably run across a listicle or two — maybe even a list of must-read books. And you've probably run across some sort of moral panic over listicles. Apparently, numbered lists on the Internet are destroying modern literature as we know it. But before you break out the pitchforks and torches, you should know that the so-called “listicle” and the modern novel are just about the same age. The first listicle and the first novel were both penned sometime in the early 11th century, and they were both (naturally) written by women.

It all goes back to Sei Shonagon, a lady-in-waiting and wisecracking poet in 1000 CE, Heian Period Japan. The Middle Heian Period was a pretty wild time to be alive if you were in the Japanese upper class (if you were a peasant, it was pretty much the same old farming and toil). Noblewomen were expected to grow their hair well past their toes, to crawl around their chambers instead of walking, and to completely black out their teeth—white teeth were considered gross and unsightly. A lady’s mouth was meant to be a perfectly black hole of nothingness. Just a whole different set of unrealistic beauty standards (Sei pulled it off pretty well, though).

Heian Japan wasn’t all bad for women, though. Writing in Japanese was considered women’s work, because only men were allowed to use the more formal Chinese. But women could own property and access education. Marriage was a fairly lax institution—most noblewomen had a roster of “secret” lovers, and divorce was pretty simple (if a husband and wife stopped hanging out, they were basically divorced).

I first came across the Heian ladies and their fabulous hairstyles in freshman year of college. I'd chosen "Manga Genji" as my Freshman Year Seminar, because it was the closest thing to studying comic books that I could find. The class was on The Tale of Genji , widely considered the first modern novel ever written, and its modern manga adaptations. We spent the semester reading about Prince Genji and his various adventures (spoiler alert: all of his adventures involve sleeping with different women and being handsome). A total of one day of class was spent on the other important writers of Heian Japan, but that's when I fell madly in love with the queen of pre-medieval Japanese listicles.

Enter Sei Shonagon, lady-in-waiting to the Empress Teishi. Sei Shonagon’s writing was circulated at court, and she soon became popular for The Pillow Book, so named because Heian courtiers would sometimes keep diaries in their wooden pillows (ouch). The Pillow Book is a rambling collection of Sei’s poetry, observations, and complaints, mostly written as a series of lists. Her list headings range from Things That Quicken the Heart to Things That Give an Unclean Feeling to Awkward Things. Sei didn’t pull any punches, either. Under Hateful Things, she lists this oh-so-romantic moment:

A lover who is leaving at dawn announces that he has to find his fan and his paper. ‘I know I put them somewhere last night,’ he says. Since it is pitch dark, he gropes about the room, bumping into the furniture and muttering, ‘Strange! Where on earth can they be?’ …'Hateful' is an understatement.

A lot of the lists mention how annoying it is when your lover makes a scene instead of leaving quietly at dawn (amiright, ladies?).

The Tale of Genji was an interesting read (what's not to like about a sexy prince lying to women for 1120 pages?), but Sei Shonagon's poetry just got me. I downloaded The Pillow Book, since Sei's writing felt well-suited to the screen, and I would dip into her lists whenever college life became overwhelmingly hateful, unclean, or awkward. Sei did not disappoint.

She had an acerbic wit. Under Rare Things she lists (among other things):

A pair of tweezers that can actually pull out hairs properly.

Two people living together who continue to be overawed by each other’s excellence.

Infuriating Things brings us:

A very ordinary person, who beams inanely as she prattles on.

A man you’ve had to conceal in some unsatisfactory hiding place, who then begins to snore.

The list of Things People Despise is made up of only two points:

A crumbling earth wall.

People who have a reputation for being exceptionally good-natured.

Things that Quicken the Heart has a beautiful line on feelin' yourself:

To wash your hair, apply your makeup and put on clothes that are well-scented with incense. Even if you're somewhere where no one special will see you, you still feel a heady sense of pleasure inside.

Things That Should Be Short includes:

A lamp stand

A young girl’s speech.

Even the prose, non-listicle chapters share her signature dry humor. Her brief musing on the beauty of lying awake on a rainy night ends with the line:

Everything that cries in the night is wonderful. With the exception, of course, of babies.

If only Sei Shonagon had lived to see a world of sub-tweets and texting.

But, as we know, Sei wasn’t the only high-profile female writer of her day. There were two Empresses kicking around the capital city of Heian-kyo (modern Kyoto), always vying for the Emperor’s attention. The second Empress, Empress Shoshi, hired her own literary lady-in-waiting to challenge Sei’s reputation. Empress Shoshi’s writer-in-residence was Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji.

That’s right: the first listicle "blog" more or less pre-dated the first novel. Murasaki’s Tale of Genji is a lengthy, romantic tome, full of pining and love triangles. The Heian nobles ate it up. Sei Shonagon, however, was not so much a fan. Murasaki was shy and sensitive, a reclusive novelist dedicated to her craft. Sei, by all accounts, was a sharp-tongued diva who lived for court drama. The two writers enjoyed a healthy rivalry.

Or rather, they lowkey hated each other. Murasaki’s diary mentions Sei in a less-than-flattering light:

Sei Shōnagon... was dreadfully conceited. She thought herself so clever, littered her writing with Chinese characters, [which] left a great deal to be desired.

Sei never stooped so low as to insult Murasaki back, but she did have a very clear message to all her haters:

I must always come first in people’s affections. Otherwise, I would far rather be hated... In fact, I would rather die than be loved but come second or third.

Oh, Sei. Born one millennium too soon for Tumblr and passive aggressive Facebook statuses. Her Pillow Book has been a bitter, critical friend to me many times over the years. Sei Shonagon may have never seen a viral cat video in her life, but her clever, list-based writing style has certainly lived on. And her quips are surprisingly relatable, so many years later. As Sei herself said:

In life there are two things which are dependable. The pleasures of the flesh and the pleasures of literature.

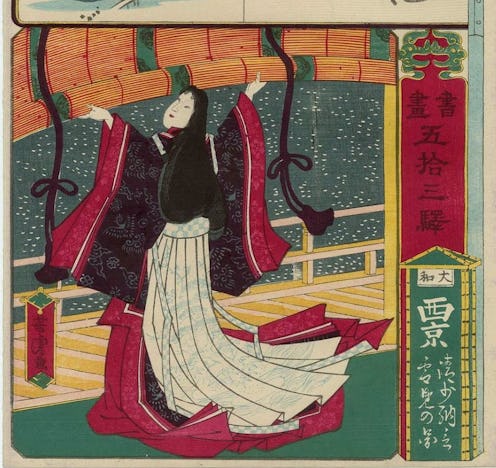

Images: Utagawa Yoshitora/Wikipedia Commons, Kobayashi Kiyochika/Wikipedia Commons, Giphy (4)