"I think in social justice we throw around the term 'bringing awareness' a lot without discussing what that really means," artist Mirabelle Jones, creator of the book series "JARRING III," tells Bustle over email. "By 'bringing awareness' to sexual assault, I mean talking about what it really looks like for real survivors as opposed to the myths society tells us about sexual assault and rape." Through 150 artistic books in three designs, each of which tells the tremendously varied stories of real survivors, Jones is showing what the problem really looks like — not from the perspective of the news media, but straight from the victims themselves.

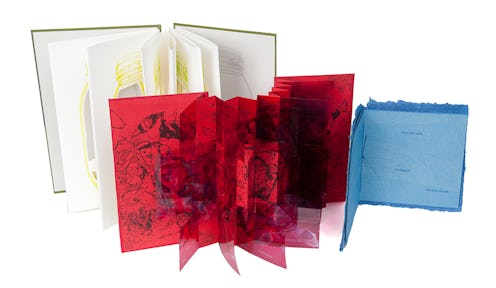

The books use intricate shapes to visually convey the gravity and prevalence of the sexual assault epidemic. One has a cut-out of a lime green jar, with the stories appearing on slips of paper inside the jar that amass into one giant pile as you flip the pages. Another is red with translucent sheets that overlay to create a visible cacophony of experiences. The third is sky blue with silk and glass, mirroring the delicacy of the personal narratives inside.

Jones is raising money to tour the artwork around the country while giving workshops on speaking out about sexual assault through art. She hopes each set will end up in a different museum or library collection. When she sells them, 100 percent of the proceeds will go to rape crisis centers.

Jones's personal experience with sexual assault spurred her efforts to tell other victims' stories. After being drugged and raped during graduate school, she had a rape kit performed, only to have no action be taken with it by authorities. She did, however, receive support from a Bay Area Women Against Rape advocate. "I found myself wondering how many survivors go through the process alone, unaware that there are resources in place to help them," she tells Bustle. "I knew I wanted to do something to raise awareness about and support these resources."

So, she put out a call on her website for survivors to submit their stories. The details of 22 assaults, including her own, are in the books. "One thing that struck me was that the narratives were so different from one another," she says, explaining that they varied in every aspect from how recently the assault occurred to who the perpetrator was. "While the stories we hear in pop culture express a very specific narrative that perpetuates a set of myths about sexual assault, these stories, like my own, were real and were true," she says.

When she discusses myths about sexual assault, Jones is referring to a slew of ideas about what supposedly mitigates sexual misconduct and what constitutes consent. These can make people doubt others' stories as well as their own. "Some survivors may not see what happened to them as 'rape' because they consented to some other sexual or non-sexual activity," she says. "This thinking replicates one of the myths of rape culture: that if you consent to something, you consent to everything."

The survivors whose stories she gathered encountered many more misconceptions that impeded their process of healing and seeking justice. They said they'd been told that you can't be raped by a partner, that the absence of "no" means "yes," that victims who were drunk at the time can't be believed, and that if they did not report the crime, they must have been OK with it. She also heard from people who avoided seeking help because they were sexually abused as children and bought into the myth that they were irrevocably broken.

"There is no myth contained in these books," she says. Hopefully, reading them can be a cathartic experience for people whose own assaults have been invalidated and an educational one for those whose knowledge of the issue has come from less direct and often toxic sources.

Images: Courtesy of Mirabelle Jones; Michelle Yoder Photography; Alex Brown Photography(2)