Entertainment

A Tribute to Hollywood's Best Supporting Man

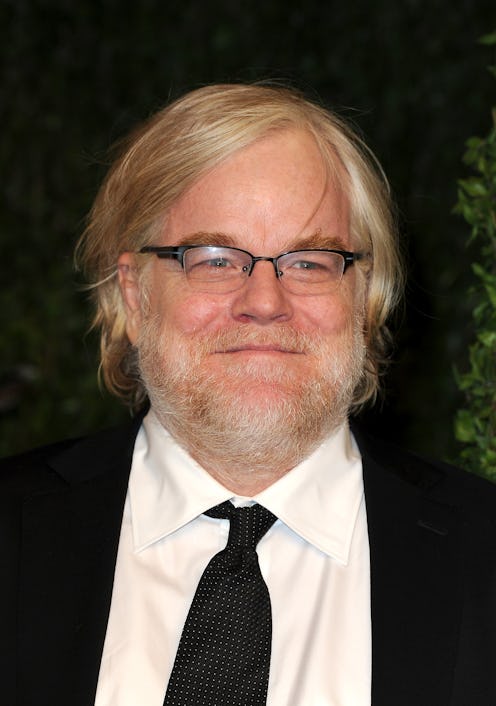

In Hollywood, actors tend to fall into a few categories. There are the celebrities (the Brad Pitts and Sandra Bullocks — the people whose movies make millions and whose lives sell magazines); the unknowns (the struggling newcomers just waiting for a hit); the character actors (the people you know you recognize, but just can't quite place). And then there is Philip Seymour Hoffman. Hoffman, who died Sunday from an apparent drug overdose, didn't fit into any of those categories. He was a Hollywood anomaly; famous, but not a tabloid figure. A familiar face, but not a household name. He, with the mile-long resume and Academy Award, was far more than just "that guy from that movie," yet he wasn't a star. He fell into his own category, a distinct Philip Seymour Hoffman genre marked by one key trait: He was just one of those guys that everyone loved.

The first time I saw Philip Seymour Hoffman in a movie, I was 11, and Along Came Polly was playing on TV. The movie wasn't particularly good; in fact, it was kind of horrible. Ben Stiller and Jennifer Aniston had no chemistry, there was an ferret tagging along for no reason, and even at 11, the idea that the main female character's single flaw was her messy apartment was more than a little annoying. And yet it made me laugh. I found myself cracking up every time Sandy (Hoffman), Reuben's (Stiller) crude, big-mouthed friend, appeared on screen, shouting at Alec Baldwin in a conference room and telling Reuben that he had a little "situation." (Note: I was probably a bit too young to be watching Along Came Polly.) It wasn't the movie that was so amusing — it was Hoffman's performance. Everything he said, no matter how ridiculous or badly written, just worked. The guy was just funny.

Over the next few years, I saw a handful of more Hoffman movies, most notably Almost Famous, viewed in a ninth grade Journalism class because my teacher deemed it "basically a necessity." With each film, I found myself falling more and more in love with his talent, completely awed by the ability of one man — one I'd barely even heard of, no less! — to be so many people at once. He was Lester Bangs, he was Truman Capote, he was Dean Trumbell and Scotty J.; in every role, Hoffman was transformative. He was a rare, genius, chameleon of an actor. Yet, in all of his performances, no matter how different, one character trait remained the same: He was vivacious.

On screen, even when just playing a supporting role (the actor was very rarely a leading man, with the exception of his Oscar-winning Capote), Hoffman seemed alive. When he played happy, it was contagious; when he was angry, it was all-consuming. Whether he was preaching the perks of being "uncool" in Almost Famous or singing "Slow Boat to China" in The Master, Hoffman was always totally, incomparably alive, present in a way that even the best of his peers never were. He didn't just embody a character, or just read his lines. He clearly loved the people he portrayed.

Hoffman, as learned through his many interviews, adored playing a part. He thrived off of taking on the most complex, difficult roles he could find, because, to him, they exemplified the best and worst of humanity. It wasn't acting he so enjoyed — "that's absolutely torturous," he once said — but the life he got to bleed into his characters. And thanks to the talents he possessed and the roles he was given, that fans of the actor reciprocated that ever-present love.

Hoffman's death will be felt by many people: those who've known him for years, from the days of Scent of a Woman and Boogie Nights; those, like me, who found him midway through, from Almost Famous or Punch-Drunk Love; and those who are just discovering him now, in Moneyball and Catching Fire. It doesn't matter when he first came into your life, though; the important thing is that he did. Watching Philip Seymour Hoffman act was a blessing and a privilege, and I can only imagine that getting to know him, in person, was an even greater experience. He may not have been a celebrity, but there's no denying a simple fact: The man just made everything better.