Books

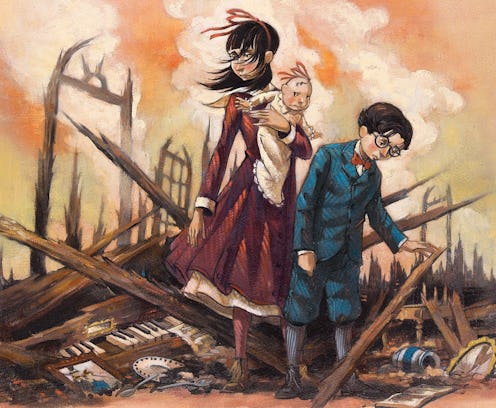

'A Series Of Unfortunate Events' And Justice

There are so many wonderful children's books out there: beloved books that defined our childhoods and taught us important life lessons. So why don't you go read one of those books, instead of this dreary article on A Series of Unfortunate Events? You could be reading about a harmless club of babysitters, instead of reliving that ghastly moment when the Baudelaire children discovered that their parents had died in a terrible fire. You could read about the whimsical adventures of a dull little girl from Kansas, instead of thinking about the treachery and bad personal hygiene of Count Olaf. You could even read about an orphan with wizard powers who goes to a magical school, instead of reading about three orphans without wizard powers, who never go anywhere pleasant at all.

But, if you (like me) already ruined your childhood by reading about Lemony Snicket's wretched orphans and their luckless adventures, I'm afraid it's far too late. You've probably already seen the miserable movie, gotten excited about the nasty Netflix series, and re-watched the foul fan-made trailer. And now you are reading this awful article, about how A Series of Unfortunate Events taught me about justice (and other even more dreadful things).

I can't remember when I first picked up The Bad Beginning (someone must have decided that I was too happy as a child, and given me that book to balance things out). I do, however, remember going to the library to hunt down one of the later books in A Series of Unfortunate Events, and asking the librarian where I could find the books by Lemony Snicket. Both the librarian and my mother shared a condescending smile, and informed me that "Lemony Snicket" was not a real name, and I couldn't possibly be remembering it correctly. Had I been a bit older, I could have said, "Well, yes, Lemony Snicket is a pseudonym — a word which here means, 'a made up name used to trick librarians'—and the author's real name is Daniel Handler."

But I was not older, so I kept insisting that I was looking for the books by Lemony Snicket. Finally, the irritated librarian searched the name in order to prove to me that no such person existed — instead, to her horror, she discovered that there was an entire series by Mr. Snicket, and I got my book.

Was that librarian particularly evil or cruel? Not at all, but she would have fit in perfectly with the many well-meaning adults that the Baudelaires encounter. Because the true misfortune of A Series of Unfortunate Events isn't merely that Count Olaf (and his wicked girlfriend Esme Squalor) are out to get the orphans. The most disturbing part of every book is that most of the "good" adults just don't listen to the children. The adults get too caught up in their own fears, like Aunt Josephine. Or they choose to follow the rules over helping the children, like Charles. Or they just don't believe the children about Count Olaf, like the easily fooled Mr. Poe.

Those books taught me a lot of things growing up. I learned the difference between "anxious" and "nervous," the meaning of the word "ersatz," and the function of a concierge. And besides all that vocabulary, they were the funniest kids' books I ever read, filled with wry humor and meta-fictional author asides. They still hold up rereading them now — a lot of the best jokes flew over my head back in the day.

For instance, almost all of Sunny's "babytalk" is made up of allusions: she says "Ackroyd" to describe a murder, as in Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd; "Rosebud" to mean sled, a la Citizen Kane; and "Busheney!" to mean "You're an evil man with no concern whatsoever for other people!" as a reference to a certain president and vice president of the U.S.

But above all, those books don't talk down to children. The Baudelaire's lives are genuinely filled with misery, and it's often because the well-intentioned adults around them repeatedly choose the system over the children's welfare. Yes, the orphans live in a vaguely Gothic world of no particular time period, but the social commentary on our own world is inescapable: the super rich obsess over what's "in" and only bother adopting orphans when it's fashionable. Schools are concerned with teaching to a test (and hosting the principal's six-hour violin recitals), rather than inspiring their students. The working class laborers at the Lucky Smells Lumber Mill are paid in coupons that they will never be able to use, because they have no money. The kindest of adults, like Jerome Squalor or Hector the Handyman, would rather run away than face anything uncomfortable, regardless of what's right or wrong.

For the most part, adults in A Series of Unfortunate Events blindly follow the rules. Even when they try to mete out justice, they end up with an innocent man dead, the three orphans unfairly accused of murder, and the real Count Olaf free to do his dastardly deeds (like being an actor and never showering).

But here's where Lemony Snicket makes things interesting. Because, although the children in his books usually start out as good, kind, and well-read, they are often forced to do wicked things to stay alive. And I don't just mean the snotty Carmelita Spats — Klaus's sort-of girlfriend Fiona joins Olaf to be with her brother, the Hook-Handed Man. As the books go on, the three Baudelaires are forced to use their various talents to craft disguises, lie, and steal with alarming frequency.

And even the evil people aren't all black and white. The cruel Hook-Handed Man still cares for his little sister. The three carnival "freaks" start out good, but rejection from society drives them to join Olaf. Even Olaf himself is complicated: in The Slippery Slope, we find out that he's working for a higher evil, because every adult in the series seems to have a boss. In The End it's implied that he and Kit Snicket were once in love (I really hope there's more on that when I eventually get around to reading the new prequels). He even comes to respect the orphans in the end of The End, although it doesn't right all the wrongs he has done (let's not forget that it's still incredibly creepy when he hits on 14-year-old Violet in the first book).

No one is wholly innocent. No one has had an easy childhood. But at the same time, Snicket shows us that the Baudelaires are determined to resist: They will not let this world warp them into evil without a fight. They will not blindly follow the rules, because they've been through enough to thoroughly mistrust the rules. They eat the forbidden apples in the last book to save their own lives, while everyone else would rather be killed by mushrooms — one of the more heavy-handed allusions, but Snicket makes it work.

Reading those books as a kid, and even rereading them as an adult, the lessons don't get old. OK, so you can find commentary on the justice system, income inequality, and the dismal state of education in other books, too. But A Series of Unfortunate Events is unique in having sort of an anti-moral at its core: Don't grow up to be the well-meaning adult who follows the rules of society. Don't underestimate children (or their electrical engineering abilities). Read widely. And above all, think for yourself.

Images: Netflix/YouTube; sploid gif; giphy (3)