News

I Met Steven Avery Before 'Making A Murderer'

Years before I was asked to talk about Steven Avery — in Glamour UK, on NPR, on an AMA chat on Reddit (where I took some flak) — I had already covered some high-publicity murder trials. One in California stands out. The mastermind was a college kid named Dana Ewell. He lured his parents and sister to the family home in the Sunnyside neighborhood of Fresno. Dale, Glee, and Tiffany Ewell were then shot to death by Dana's buddy, who was lying in wait on that Easter Day in 1992.

For several years, the two men taunted the police who were investigating them, and it looked like Ewell might inherit his father's $8 million estate. But ultimately both he and his buddy were convicted of the murders and sentenced to life in prison. In one way, that case was like all the other murder cases I had covered. I had never heard of, nor laid eyes on, the accused killers until after they had been arrested and brought to court. They were strangers.

The Wisconsin man who would become the central figure in Netflix's docuseries Making a Murderer was different.

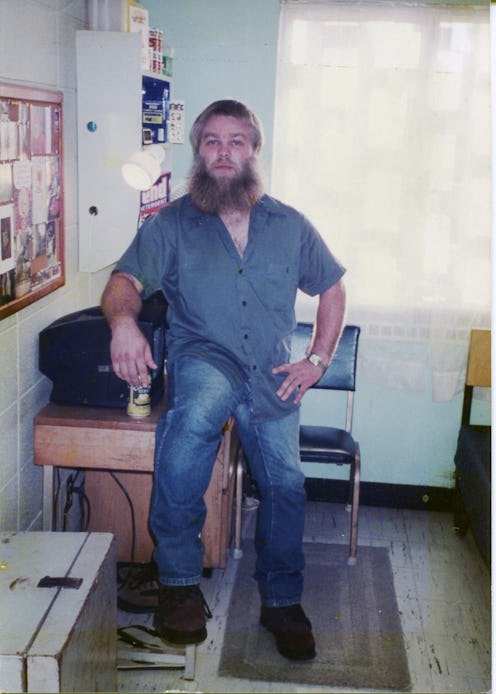

I met Steven Avery on Sept. 11, 2003, soon after breaking a story that he would be freed from prison after serving 18 years of a 32-year sentence for sexual assault. New DNA testing, on a single remaining hair preserved as evidence, proved the 1985 assault had been committed by another man.

The day he crossed through the prison gates, Avery, then 41, sported a shaved head and a graying beard that stretched to near his belly button. He smiled and laughed, if a bit uncomfortably, telling a phalanx of reporters and cameras: "I'm out! Feels wonderful."

Three months later, I visited Avery at his parents' Manitowoc County home, which appeared in many scenes in Making a Murderer. Avery and I sat a few feet across the kitchen table from each other for an interview, as he described struggling with his new freedom. His blood pressure had actually risen since he left prison. "Sometimes I feel like it's easier in there," he told me.

I thought that might be the last time I would see him.

Then came the news, two years later.

On Halloween of 2005, a 25-year-old photographer named Teresa Halbach had gone missing, and was last seen alive by Avery outside his home. The first stories we wrote were about the search for Halbach, and then about the revelation that she had been murdered. During those tense days, it was clear Avery was the main suspect, but no arrests had been made. Avery was still free.

I visited him again, this time at his family's cabin. He was still mostly soft-spoken, answering questions with short answers. But this time he seemed agitated, too. "Sometimes, I got to break down," he told me, admitting he couldn't help but cry at times. "I try not to let it happen."

What wasn't significant to me at that moment was that sitting in the kitchen with us was Avery's 16-year-old nephew, Brendan Dassey. One of the photographs we ran in my newspaper, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, showed the two of them staring across the table at each other.

As is detailed in Making A Murderer, Avery and Dassey were found guilty of Halbach's murder after separate trials in 2007. Both received life sentences.

Which meant that, for the first time in more than 20 years as a reporter, I had been sitting across a table from two men who would later be convicted of murder.

It would be a startling thing to realize.

After that visit to the cabin, I returned to Milwaukee, staying in touch with Avery by phone while continuing to press law enforcement officials for more information about Halbach's murder.

Two days after the cabin interview, shortly before 1 p.m. on a Wednesday, I called Avery again to check in, to see if there were any developments, had he been visited again by the police, and so on.

The conversation ended abruptly after he told me as he was being put under arrest.

"I'm going to jail. I can't talk to you no more."

That's the last time we ever spoke.

Images: Netflix; Fox News