News

5 Ways America's Prison System Mimics Slavery

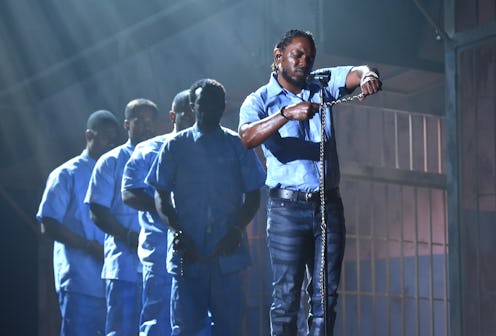

The sound of chains, heavy and oppressive, kicked off Kendrick Lamar's performance at the 2016 Grammy Awards. There was nothing subtle about it — he was reminding America that racial oppression is, and always has been, a primary factor of the U.S. prison system. Lamar's performance was a bold representation of the prison-industrial complex.

For those who need a refresher, "the prison-industrial complex" refers to the overlapping interests of the government and private companies in mass incarceration, and the fundamental relationship between punishment and commerce. In America, imprisoned individuals are forced to work for corporations. And the way in which they are thrown into this labor echoes the kind of slavery we learned about in our history books — the kind of slavery Lamar depicted at the Grammys.

In his song "The Blacker the Berry," Kendrick Lamar proclaims, "I said they treat me like a slave, cah' me black / Woi, we feel a whole heap of pain, cah' we black." He continues on with, "They put me in a chain." Some may hear this as nothing more than imagery, but it's a reality for millions of black people who are incarcerated.

Leandra T. Lambert, a black seminarian in Brooklyn and a colleague of mine from Harvard University, tells Bustle that "the 21st century chattel system" has robbed many blacks of their voice for far too long. She said that Lamar's performance was significant, forcing us to see injustices that most of us have been blind to.

Though problems with the system extend much farther back, the prison-industrial complex as we know it was born in the '80s, when the War on Drugs was enacted in full force under President Reagan. Between 1980 and 1984, FBI anti-drug funding went from $8 million to $95 million. At the same time, funding for drug treatment and prevention was significantly reduced. Inner-city, underserved communities of color were targeted. Black men and women were sent to prison at alarmingly fast rates, and for nonviolent crimes.

Fast-forward a few decades later and our country is looking at mass incarceration. We send more people to prison than any other nation on Earth, and people of color make up most of that incarcerated population. Here are five ways the prison-industrial complex functions as a new, legal form of slavery.

1. Incarcerated Individuals (Who Are Mostly People Of Color) Are Legally The Property Of The Government

In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was passed, abolishing slavery. There was a significant loophole in the Amendment, though: It stated that slavery and involuntary servitude are illegal, "except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." In other words, individuals who are imprisoned are technically considered the property of the state or federal government. Sound familiar?

Black people comprise 13 percent of the American population, yet they are six times more likely to be thrown behind bars than white people. They and Hispanics make up 58 percent of the prison population. This means that at any given time, a disproportionate number of people of color are forced into hard labor (many of whom have committed nonviolent drug-related crimes).

An Atlantic documentary called Angola for Life: Rehabilitation and Reform Inside the Louisiana State Penitentiary shows footage of prison labor on what was once a Southern plantation. It may have been filmed recently, but as the film puts it, "the stench of slavery and racial oppression lingers."

2. Prisoners Are Leased To Private Companies For Mandatory Labor

As early as the start of the 19th century, states were leasing out imprisoned individuals "to private bidders to be housed and worked as slaves," as Harvard professor and Director of the Prison Studies Project Kaia Stern writes in her latest book, Voices From American Prisons: Faith, Education, and Healing . This labor was specifically used for production, and the same thing still happens today.

Every day, prisons drum up contracts with private companies who have a lot to gain from cheap, faceless labor. In 2013, Christopher Petrella wrote an article for Truthout called "The Legacy of Chattel Slavery," shedding light on these partnerships. He says that holding so many blacks behind bars "still functions primarily as a source of profit extraction, rather than as a resource for rehabilitation."

Should any incarcerated individuals refuse to be rented like property, they are locked up in solitary confinement or they have family visitation rights taken from them, among many other brutal consequences. So the next time you sit in an office chair or put on a push-up bra, know that there's a strong likelihood that an individual in the prison system was forced to build it or sew it.

3. Prisoners Work And Live In Inhumane Conditions

It's not uncommon for individuals behind bars — including women — to be shackled in chains during labor. The tasks they are given are often dangerous, and their safety is rarely taken into account. They work for long hours, sometimes with no end in sight. "Convict leasing" is said to actually be better for the companies than slavery was for slave owners, because they don't even have to worry about maintaining the health of their workers.

For example, after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, BP decided to exploit incarcerated folks in Louisiana prisons to take care of the mess they created. They leased out work crews and paid them little. Out of all the states in America, Louisiana boasts the highest incarceration rate, and 70 percent of their prisoners are black.

When I spoke with Stern, she reminded me that popular media often fails to cover these topics, which is precisely why we are not familiar with the violence and "the soul-crushing isolation that is the everyday life for millions of people." Why is it kept from us, though? Because there is much to gain financially from the sweat and toil of people of color, and no one seems to want to hear about it.

4. Prisoners Are Paid Next To Nothing While Corporations Profit Huge Amounts Off Of Their Labor

To say that prisoners make less than the minimum wage wouldn't even begin to crack the surface. Many of them work full-time for only pennies a day. There are some who make up to $2 an hour, but overall, Stern says, "the prison population receives 'slave wages.'" The imprisoned population is vulnerable and unprotected. They have no means of forming a union, which would allow them to fight for basic workers rights and fairer wages, and they cannot vote to affect change.

Meanwhile, Unicor, an American government corporation that exploits penal labor to produce goods and services, profits $900 million a year. They're known to pay prison work crews as little as 23 cents an hour. In 2013, Unicor had federal prisoners stitch $100 million worth of military uniforms, crushing numerous small businesses who just can't compete, as they must pay a minimum wage to their workers.

They falsely wrap up this injustice by labeling it a "jobs training program," but it's clear that the incarcerated aren't being taught a set of skills as a means of reform. The prison-industrial complex is much more concerned with profiting off of these human beings in chains, as if they are nothing more than real estate.

5. The System Dehumanizes Incarcerated Individuals

As someone who has worked in the penal system for 20 years, Stern writes about prison as "a totalizing institution that represents modern systems of domination and social control." The prison-industrial complex turns people into tools used to bring profit to huge corporations. There's no care for reform or justice — the two things that are supposed to rule our criminal justice system. Denying people their basic humanity in this way was precisely what we saw in slavery all those years ago; it's just executed in a different way today.

Upon being released from prison, prisoners' rights are still often kept from them. They are ineligible for many jobs, they're denied public benefits and housing, and in many cases they're not permitted to vote. There are even women who are briefly sent to prison for drug addiction or victimless crimes who lose custody of their children without even being given the chance to fight for them.

In her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration and the Age of Colorblindness , legal scholar and civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander calls life after prison a parallel to the slavery and Jim Crow era, "in which discrimination in nearly every aspect of social, political, and economic life is perfectly legal."

While Kendrick Lamar's statement may have seemed controversial to some, there's simply no denying that our criminal justice system is inherently racist.