A couple of years ago, I decided that I would never wear shapewear again. Not because I think it's "wrong" to do so per se (if that choice is coming from a place of personal preference). Nor was it because looking through the history of shapewear revealed just how messed up beauty standards have been since the dawn of civilization. My decision stemmed mostly from the epiphany that I didn't need shapewear at all. It's main purpose in my own life was to serve up protection against some serious thigh chafing. And why should I have to suck in my stomach, ass, and lower thighs to achieve that?

I often feel lucky, because despite a bad body image here or there (one that usually consists of chastising myself for not having the elusive glowing face magazines tell me is "in" or yelling at my curls for not looking like Julia Roberts' in Pretty Woman or being frustrated that my bottom, although very wide, just isn't very plump), I'm usually pretty comfortable and confident in my fat body.

Unfortunately, feeling comfortable and confident in one's body isn't the status quo. It's not the mantra being preached when you open up a publication while waiting in line at the grocery store to buy some Cheez-Its. It's not the message we get when ads are telling us that nipping, sucking, and hiding are a woman's principal sartorial goals in this existence. And it's certainly not a message that rings through when you look at the evolution of shapewear trends over time. Here's what I mean.

1. Ancient Crete: Boobs Out & Waist In

The earliest recorded version of shapewear dates back to Mycenaean Greece, likely sometime between 1,600 to 1,100 BC. According to lingerie resource and boutique Dollhouse Bettie, the ancient Minoans who lived on Crete long before the Athenian invasion weren't as concerned with decency and nudity as their conquerers. "While the Cretans had celebrated the female form in all its glorious sensuality, and created undergarments to emphasize the breasts, hips, and waist, lingerie in Ancient Greece was another matter entirely," wrote Dollhouse Bettie. "The Cretan crinoline and corset would have had no place in Athenian society, and wearing such items would have been beyond obscene and in no way tolerated."

Artwork of the time tends to suggest that the Minoan (or ancient Cretan) women would wear their breasts entirely out, nipples free and pushed up by corsetry that simultaneously brought in the waist. Some Ancient Greek bras, like mastoeides, actually helped push breasts out of clothing. But what's also interesting to note is that in several works, women are depicted as having the aforementioned hourglass figure, but with rather strong, broad shoulders and arms. The dainty figure we'll see created by shapewear later on didn't necessarily apply here. Rather, emphasis seems to have been placed on striking a balance between the curves of femininity and the physical strength of masculinity.

2. Hellenic Greece: Metal Embellishments

According to the Encyclopedia Of Fashion, "The societies of the Greek island of Crete [...] and those of Hellenic Greece (the period before Alexander The Great (356 to 323 BCE) [...] also learned the art of metalwork, and they made decorative metal girdles an important part of their fashionable dress." Oh, girdles. The Role Of Women In The Art Of Ancient Greece also explains that "there are numerous references to girdles in the Iliad and the Odyssey ."

Girdles were also made of linens and soft leather during this time, more often than not facilitating the hourglass shape that had already started to be a thing equatable to desirability. Early manifestations of the girdle seem to have had an element of mysteriousness to them — like an additional layer of clothing separating mere mortals from beautiful women.

Take this passage from the Iliad : "She spake, and loosed from her bosom the broidered girdle [...] curiously-wrought, wherein are fashioned all manner of allurements; therein is love, therein desire, therein dalliance–beguilement that steals the wits even of the wise.” This early shapewear was a symbol of sexuality, no doubt, but one that came in the form of a garment that ultimately helped change the shape of your natural body.

3. Ancient Rome: Breast Binders

Besides contributing to modern incarnations of technology, warfare, and politics, the Ancient Romans also gave us a little something else: breast binders. Unlike the Minoans who opted for free nipples and perked boobies, the beauty standard for women at the time was "slender, with small breasts and large hips," according to Forbes. "A breastband (strophium) similar to a bandeau top was used to bind breasts, and according to historical records, reputable women kept the breastbands on during sex, to the dismay of their husbands."

Oftentimes when we consider shapewear, images of tummies tucked and enhanced waists come to mind — but very rarely do I personally conjure up images of shrinking the ta-tas. I cannot help but wonder if this marked a shift in general perception of female nudity. Were breasts starting to become indecent? Sinful? Shameful? Only for the bedroom, and maybe not even then?

These days, chest binders can be extreme sources of empowerment for LGBTQ individuals, of course, particularly for transgender men, non-binary AMAB individuals, or anyone who simply doesn't feel as at-home in a body that has boobs. But their origins seem, well, a little rooted in sexism. Like, the kind of sexism we're still fighting thousands of years down the line because humans still freak the eff out when they see a mother breastfeeding in public.

4. The Middle Ages: Bodices & Paste

During the Middle Ages — that big chunk of time between the 5th and 15th centuries — women were gifted with "tightly laced bodices stiffened with paste to control and smooth their figures," as Slate reported. With the exception of the Romans, the hourglass figure seems to have been the most coveted since basically forever. But it's curious that there's little to suggest weight loss was also a principal goal. Most research (again, with the exception of that surrounding Rome) implies that "ideal" female bodies were about the shape more so than the size. So in a way, the term shapewear was the most accurate its ever been back in the day.

Although the metal girdles of Hellenic Greece don't sound like the comfiest things to wear, the Middle Ages seem to mark a focus on more painful routines — the whole suffering for the sake of beauty thing. Just picture Elizabeth from Pirates Of The Caribbean fainting into the sea because her corset didn't allow her to breathe. That's what the Middle Ages set us up for.

5. Elizabethan Era: Steel & Petticoats

And then it became about the hips. Come the later 1500s, concerns drifted downwards, large petticoats going underneath dresses to create the illusion of width, while steel corsetry was designed to flatten and conceal the chest. According to "History Of The Elizabethan Corset," "In the 16th century, the corset was not meant to draw in the waist and create an hourglass figure; rather, it was designed to mold the torso into a cylindrical shape, and to flatten and raise the bust line [...] On the whole, it was a fashionably flat-torsoed shape, rather than a tiny waist, that the corset was designed to achieve."

Petticoats might not be a go-to symbol of shapewear as far our modern interpretations go, but ultimately, that's kind of what they were (and remain): Items designed to mold the shape into whatever is "fashionable" at the time. As breasts became parts of the body in need of being concealed, perhaps there was a desire for women to show off their femininity in other, less sexually-connoted ways. Enter the petticoat, which suggests width at the hips. In other words, an optimal childbearing body.

6. Victorian Era: Whale Bones & Other Extremes

What is it with the Victorian Era and its damned extremes in the late 19th century? It was all about sexual restraint and "morality" and yet we were putting women in whatever would make them look the most voluptuous. "Women squeezed themselves into corsets that molded their figures to fit the Victorian ideal: A voluptuous bosom atop a teensy waist," reported NPR. As HerRoom.com noted in its iconographic of shapewear through time, Victorian shapewear was all about "the corset, made from heavy canvas with whale bone or steel, [which] created an extreme hourglass shape." It was so tight, in fact, that "Victorian women often needed help [...] They would lay on the floor while someone put a foot on their back and pull the corset stays as hard as they could to tighten them."

In keeping with history, it would seem the hourglass was, indeed, still amongst the most desirable body types women of the world could offer. So why not suck your body into the tightest whale bone corset out there to give the illusion of a waist the size of a toddler's? Seems totally reasonable, right?

Things took a turn, though. "Since corset frames were mostly made of metal, which was needed for ammunition and other military supplies (during World War I), the U.S. War Industries Board asked American women in 1917 to stop buying them. Around the same time, the modern-day bra emerged, freeing up wartime steel and women alike."

7. The 1920s: All Things Svelte

OK, so then the First World War came, and the military needed its steel. Enter the flapper aesthetic. All us fashion lovers know that the era was characterized by svelte silhouettes, "boyish" frames, and a more shapeless sartorial silhouette altogether. HerRoom.com reported that "shape was out and thin was in. Camisoles, panties, teddies, and bras were used to bind breasts and hide curves." Perhaps this was the beginning of a focus on thinness as well as shape.

So come mass and global international conflict, "Whale bone was replaced by cheaper flat spiral-steels at the beginning of the 20th century, and the corset gave way to lighter girdles in the 1920s and 1930s," according to NPR. It wasn't so much that war signaled an end of corsetry and shapewear. Rather, things had to become lighter, cheaper, and easier. In this case, the shapewear standard — and beauty standard, at that — might have more obviously been down to social and financial climate than anything else.

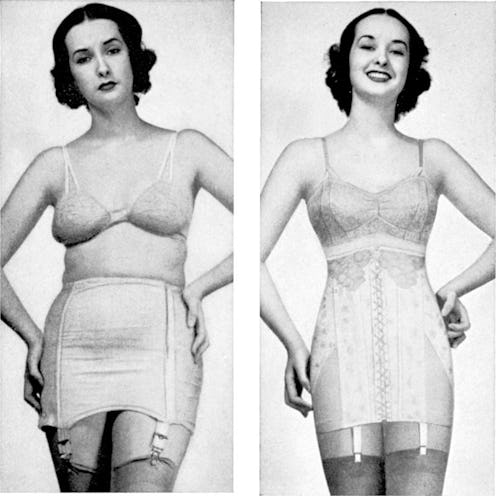

8. World War II: All About The Girdle

Dictionary definitions tend to dub girdles something of a "lightweight undergarment, worn especially by women, often partly or entirely of elastic or boned, for supporting and giving a slimmer appearance to the abdomen, hips, and buttocks." You can often see them attached to thigh-high pantyhose, and they were all the rage during World War II. The lightweight nature of the shapewear combined with the fact that it could be made of much less fabric than a petticoat or heavy duty corset made it pretty ideal for times of financial scrimping.

This is also when we begin to see shapewear as we know it today. Elasticated, tight-to-the-figure designs that serve the purpose of making the body look as thin as possible. Apparently, "Secret pockets were sewn into girdles during WWII to safekeep important documents and items," according to HerRoom. So that's a little bonus, I guess.

9. The 1950s: Hourglass Is Back

In the words of HerRoom, the '50s marked the beginning of the "boom and boob years." "Shapely figures were created with bullet, cantilevered, and padded bras. Modern materials like nylon and polyester were used with whale bone in waist-cinching girdles."

This was the era of pinup girls. No longer were boobies hidden behind constrictive fabrics and insane steel, but pushed up with the help of bras and the kind of shapewear we know and love/hate today. Like the last several decades, a certain kind of thinness remained "in." But this time around, flat tummies were accented by hourglass figures and voluptuous ta-tas. And perhaps this is when we began to reclaim our breasts after far too much time spent hiding them at all costs because #shame.

10. The 1990s: Shapewear For Slimming

Although not much is written about shapewear trends in the '90s, we know the decade was the era of the Kate Moss-esque "heroin chic" aesthetic. And browsing through vintage shapewear from the '90s on the Internet suggests this is when we started to see elasticated fabrics get even more intense. Thinness remained in, only this time, extreme thinness. So it makes sense that our shapewear would grow to match that.

I remember watching my mother in awe as she got ready for dinners and parties in the later '90s. There was never a dress that could be worn without these babies. With promises of making you look two sizes smaller sans any kind of diet or fitness change, who could possibly resist the super shaping shapewear of the times?

11. Today: Is Shapewear Taking A Turn?

In 2015, conversations surrounding body image took something of a turn. "Body positivity" became a buzzword of sorts — the notion that every body, just as it is, is worthy, beautiful, and good infiltrating more homes than arguably ever before. Thin privilege is still very real, as is the association between thinness and aspirational beauty. But we've also started to see plus size and mature models featured in Sports Illustrated . We've started to see models above a size 22 land major agency deals. We've started to see fat, unapologetic babes win globally beloved reality television shows. So maybe, just maybe, our shapewear is starting to be more about practicality than so-called perfection.

Enter a company like Bandelttes, which offers anti-chafing bands that cover only the upper thighs in the same Spanx-like fabric we might see in more formal shapewear. These products are offering a solution to a problem (chub rub!) while not suggesting that the body should be changed or molded in the process. Of course, we have a long way to go before size inclusion and fat acceptance are realized concepts. But in the meantime, it's pretty exciting to know that there are types of shapewear evolving that have nothing to do with slimming, plumping, tucking, or shaping.

The evolution of shapewear is a long and whale bone-infested one, but if there's anything it proves, it's this: Beauty standards change. They change fast. They change so fast that it's almost impossible to know what a "good body" or "bad body" is at any given moment. But maybe that's because there is no such thing as the latter.

For as long as civilizations have roamed this wacky planet, it's as though there's been a beauty standard. Standards rooted in financial, social, gender-based, and moral climates. Many of us have acquiesced to those beauty standards, perhaps out of fear of being different or the simple assumption that these standards are rooted in any kind of truth or fact (likely because they're so often presented as such). But perhaps we'll keep seeing shapewear evolve as more and more individuals recognize that there's no such thing as a universal body type. And that the standards we embody should be only those of our choosing, whether they're "in" or "dated" or our own concoction of beauty.

Want more body positivity? Check out the video below, and be sure to subscribe to Bustle's YouTube page for more inspo!

Images: Wikimedia Commons (10); Courtesy Brand