Life

7 Bizarre Valentine's Day Traditions From History

What pops to mind when somebody talks about Valentine's Day? Chances are it's chocolates, red ribbons, bizarre lingerie, and perhaps a bit of information about a Christian saint who was martyred by the Romans. (The story goes that he was killed for helping to marry Christian couples, but the reality is far from certain.) But this holiday actually isn't the creation of Hallmark; it's been a part of English-speaking tradition for a very long time, and certain Valentine's Day traditions in history should frankly be revived — either because they're hilarious, or because they're far sweeter than a half-droopy bunch of roses and some candy hearts.

Valentine's Day has been a feature of the landscape for so long that there have been studies on everything from how the colors on Valentines cards evolved to whether the medieval Valentine's Day took place in May rather than February. But either way, people have been taking the opportunity to express love and seek predictions about their marital future for centuries, and occasionally used some highly peculiar methods to do either. Fancy visiting a cemetery for a Valentine's Day date? How about bird-watching at 6 a.m., or being whipped by bits of recently skinned animal?

Here are seven Valentine's Day traditions from history that will make you look at the modern-day rituals of love with a bit of disappointment. They just lack a bit of flair by comparison. And are definitely less soggy.

1. Being Whipped With Animal Skins By Naked Romans

Valentine's Day hasn't always been a holiday on its own terms. It evolved out of the worship of Saint Valentine, a Roman martyr, but the original dates of February 13 to 15 belonged to the Roman festival of Lupercalia, riotously celebrating fertility and the start of the breeding season. According to the historian Noel Lenski in an interview by NPR, a later Pope tried to root out the less salubrious bits of this festival by layering St. Valentine's Day on top. The main bit he may have disapproved of? Women being whipped by naked dudes.

According to Plutarch, a big part of the Lupercalia festival involved young men stripping naked, running through the streets, and trying to hit any woman they came across with bits of animal skin from recently sacrificed animals. Women put themselves in the way of this treatment deliberately, because it was thought to make them fertile and help them give birth easily. Box of chocolates? Child's play.

2. Finding Your Mate By Bird-Watching

This is a bit of a weird one, because it seems to have been invented out of thin air. Medieval poet extraordinaire Geoffrey Chaucer, most famous for the Canterbury Tales, also penned a poem called the "Parlement of Foules (Parliament of Fowls)," which proposed that Valentine's Day was romantic because it was the day when birds assembled and chose their partners for the year. (Chaucer said this was an old folk belief, but it looks like he just made it up.)

This was possibly the first ever reference to Valentine's Day as a romantic holiday, but it also led to medieval love letters having a distinctly avian tinge. Sometimes, they didn't even come from the lovers themselves. On Valentine's Day 1477, a man named John Paston received two Valentines: one from his fiancé Margery Brews, and one from Margery's mother, remarking very pointedly that "Friday is Valentine's Day, when each bird chooses its mate."

The other thing this produced, though, was a belief that the first bird you saw on Valentine's Day would be the type of person you'd marry. A goldfinch meant a wealthy man, a robin a seaman, a bluebird a funny man, and a woodpecker meant no man at all.

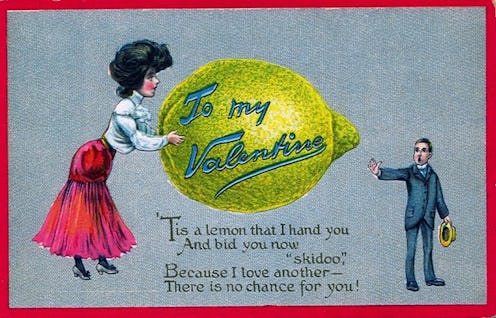

3. Vinegar Valentines

Valentine's Day hasn't always been about attracting paramours and rewarding virtuous lovers. It's also provided opportunities to tell unwanted suitors to get lost. The "vinegar Valentine," as it's called, was basically an anti-Valentine card, usually meant to inform people that their charms were decidedly unwanted. They actually fit into a wider tradition of trolling people via anonymous greeting-card, because before the Internet we had to be bullies somehow. You could insult people about their manners, their faces, their work, their relationships — all on a nice card via the mail.

The ones for Valentine's Day were particularly cruel, but apparently seriously popular: "comic valentines," of which vinegar types were a part, made up half of all Valentine card sales in America in the mid-19th century. Now we just need updated ones to deal with unwanted dick pics, exes who won't stop texting, and other 21st-century Valentine's Day problems.

4. Drawing Apostle's Names Out Of Hats

This decidedly unsexy tradition was thought to have evolved from a sexier one. Horrified 18th-century historians described the Roman Lupercalia as a cauldron of lust and sin, and said that one tradition included girls drawing names of boys from a vessel (and presumably then going to bed with them). Problem is, it looks like this never happened. But it didn't stop zealous pastors from coming up with another Valentine's Day tradition to "replace" it.

The replacement? Putting the names of the apostles on random candles on the local church altar, and giving the girls a chance to pick out those on Valentine's Day instead. Much less fun, but with its own weird power. One medieval princess, after getting the name of Saint John three times in a row on Valentine's Day, became ridiculously pious and spent her marriage (to the splendidly named Landgrave, Prince of Thuringia) praying throughout the night and only eating black bread. Fun!

5. Going To Cemeteries At Midnight For Omens Of Future Husbands

A lot of Valentine traditions from the Middle Ages appear to have revolved around women finding out, through various supernatural means, the identity of their future husbands. One way was through dreams; pinning sage leaves to your pillow, or putting a slice of wedding cake underneath, was supposed to give you prophetic visions. Another was Valentine's Day divination, where a girl put letters in a bowl of water, said some sort of chant, and hoped that the letters of a name would float to the top. But other ideas were a lot less soggy and a lot more Thriller.

According to Leigh Eric Schmidt's history of Valentine's Day traditions, one popular way of getting the universe to identify your intended was to visit the local churchyard at midnight on Valentine's, and interpret "omens" that happened while you were there. Some enterprising young people may have interpreted "omens" as "being groped on a tombstone".

6. Making A Puzzle Purse Valentine

If you want to make like a Victorian this Valentine's Day but can't get hold of any gloves (or don't feel like giving away one of a pair), make your beloved a puzzle purse Valentine instead. This beautiful and fiddly tradition meant creating folded Valentines with messages and poems that revealed themselves as they were unfolded.

It wasn't just the Victorian English, either; Sotheby's has some amazing American puzzle purses from the 1790s. They sell for about $7,000 apiece, so if you get a modern one in the mail, make sure you hold onto it; one of your descendants may make rather a lot of cash from your paramour's adoration.

7. Getting A Single Glove As A Gift

If anybody knew how to do romance at its frilliest and fluffiest, it was the Victorians. And the Victoria & Albert Museum's collection of Victorian Valentines show that their traditions for the day ranged from the elaborate (perfumed cards, paper made to look like delicate lace) to the more obscure.

One method of making your intentions known? Sending a single glove to your beloved on Valentine's Day. Gloves had been a method of wooing on Valentine's Day for ages (Samuel Pepys recommended them as romantic gifts for a Valentine in the 1600s), but this was a new innovation. It was the opposite of an insult; it was a wooing tactic. If a man gave a woman one glove on Valentine's Day and she wore it in public on Easter Sunday, it meant she returned his love. And you thought two days was a long time to text back.

Images: Collectors Weekly, Nancy Rosin, V&A Museum, Norfolk Museums, Library Of Birmingham, Museo del Prado