We remember the 1960s as an era of activism and social change. Many of the social and political movements of the past half-century can trace their roots, at least in part, to the decade of Selma and Stonewall. But it is necessary to take a closer look at the present. The civil rights movement did not end with Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, and racism was not obliterated. Today, movements like Black Lives Matter are fighting for many of the same things. Comparing photos of the '60s civil rights movement with photos of BLM demonstrates just that.

There are obvious differences between the two movements, of course. Both address the social, political, and economic rights denied to black folk in the United States, but Black Lives Matter has been able to mobilize in a way that wasn't possible 50 years ago, thanks to social media. In addition to tackling issues like education, housing discrimination, police brutality, and poverty — all of which were part of the '60s civil rights movement — BLM organizers also directly confront the ways in which black lives are not valued by society. After Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson, St. Louis rapper Tef Poe told his fellow activists that "this ain't your grandparents' civil rights movement." In some ways, it certainly isn't. Technology has transformed the ways in which people organize.

But at the same time, they're still showing up, condemning injustice, orchestrating nonviolent direct action, seeking structural change, and demanding a greater investment in black futures. In the images from the 1960s and today, as well as in the messages these movements have sent, we can recognize that over the past 50 years, many of the oppressive institutions black folks have confronted have yet to change.

Selma

The above photo marked the end of the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in March 1965. In 2015, a 50th anniversary march took place:

In 1965, this march primarily highlighted the necessity of voting rights for black Americans. By 2015, a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — which required certain states to have changes to their voting laws cleared on a federal level — had been struck down by the Supreme Court, making it possible for states to once again implement barriers to voting, like photo ID laws.

But the symbolism of the 2015 march, which commemorated the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, was significant. Activists were joined this time around by political leaders and other prominent figures, like President Obama, Jesse Jackson, and outgoing U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder. At the memorial service, Holder criticized ongoing attempts to impose voting restrictions:

It has been clear in recent years that fair and free access to the franchise is still, in some areas, under siege. Shortly after the historic election of President Obama in 2008, numerous states and jurisdictions attempted to impose rules and laws that had the effect of restricting Americans’ opportunities to vote — particularly, and disproportionately, communities of color.

Police Brutality

The fight against racist police brutality is not a new one. In the above photo, civil rights advocates took to the streets of Harlem following the events of Bloody Sunday to protest police brutality and violence. Critics of the present-day Black Lives Matter movement tend to co-opt certain parts of Dr. King's message — notably, those pertaining to nonviolence — to complain about their tactics. But these critics conveniently forget that King himself fiercely condemned police brutality in, among other times, his "I Have a Dream" speech. "There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, 'When will you be satisfied?' We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality." Occupying public spaces, blocking streets, and holding die-ins have long been effective tactics for activists fighting for social change, and trying to use King's message against black people is as inaccurate as it is offensive.

And so the fight against police brutality continues, as it must. Following the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Rekia Boyd, Treyvon Martin, and so many more black folks, activists once again took to the streets of New York City and the rest of the country to remind the world that the fight wasn't over. Ferguson is today's Selma in many ways. How many more times will this have to happen for people to stop being complacent?

Tear Gas

The above photo, which shows '60s civil rights marchers trying to avoid the tear gas used against them by Mississippi Highway Patrolmen, may as well have been taken in the past year. From Ferguson to Berkeley to Baltimore, tear gas has remained a common tool for police forces to halt activists in their tracks.

Look at that. The similarities between the two pictures are eerie. In this photo, a protester is running through tear gas during protests in Baltimore that erupted following the death of Freddie Gray in police custody. This was in April 2015. The National Guard was brought in to "calm tensions in Baltimore," but protesters faced much of the same treatment that their predecessors faced in the 1960s.

Occupying Spaces

In the above and below photos, state troopers are staring down demonstrators. Above, civil rights advocates are shown calling for an end to racial segregation in Cambridge, Maryland. Below, activists in Ferguson face Missouri state troopers on the anniversary of Michael Brown's death.

This imagery is becoming more and more common. I could have pulled a photo from the Occupy protests at University of California, Davis in 2011, or from the numerous moments when organizers confronted the Chicago Police Department for its actions. But while the fight against racism and police brutality is an old one, what happened on the streets of Ferguson mobilized people again. People finally started paying attention to something that black activists have been talking about for decades, because with social media, the images from Ferguson were impossible to escape.

The Fight Continues

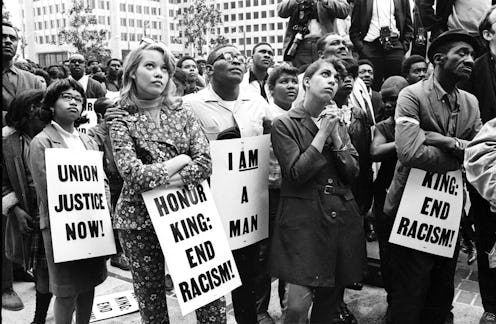

This brings me to a final photo: the one at the top of this article. It was taken in April 1968, shortly after Dr. King was assassinated. The signs bear messages which range from demanding an end to racism to fighting for the existence of unions to affirming the very humanity of black folks. It is true that things have gotten a bit better in the past 50 years — but better for whom? The powerful thing about the Black Lives Matter movement is that it centers on those who are most marginalized, and it creates spaces for those whose narratives are often silenced — such as black women, queer and trans people, undocumented folks, people who are living in poverty, those who have suffered police torture, and so on. It takes the lessons of the civil rights movement and applies them to the present. It is still fighting for an end to racism, for union justice, and for the humanity of black people.

But as Black Lives Matter cofounder Patrisse Cullors said, today's movement rejects the leadership hierarchy used by King and other '60s-era activists, choosing instead to be more democratic, and to credit all activists without putting anyone on a pedestal. This is an important distinction. The two movements share an overwhelming number of similarities, both in what they have fought for and the obstacles they face — these photos are only part of the proof.

Over the past 50 years, these movements have fought for voting rights, better access to education, critical resources, an end to housing discrimination, an end to segregated schools and neighborhoods, and vital changes to policing and mass incarceration. They have rightfully framed the systemic oppression of black people as an international human rights violation.

However, these are different movements. Even with all of their similarities, there are intergenerational tensions between '60s-era organizers and the digital natives of today. Youth activists are wary of the "new civil rights movement" mantle, because for many of them, it does not capture the gravity of the situation, and the comparison is not a balanced one. Nevertheless, it is important to study the ways in which these movements overlap, because the systematic oppression, incarceration, and murder of black people has been a state of emergency for decades. There is no more time to ask yourself the question, "What would I have done?" Because this is happening now, and if you think you would have advocated for racial justice 50 years ago, get out there and do it now. Do not be silent. Do not be complicit.

Images: Getty Images (5)