News

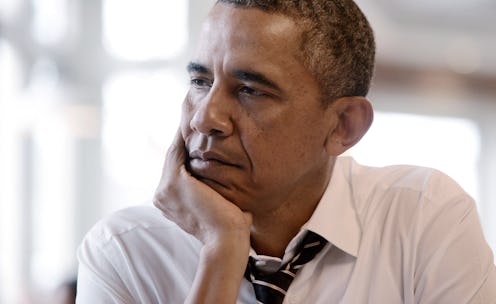

Did Obama Just Cave on Surveillance?

He may not have closed down Guantanamo, but President Obama seems determined to avoid going down in history as the leader who leaked our text messages. Instead, Obama has called for an end to the government's mass collection of American phone data, proposing that data be held outside of the government from now on, and that future government searches of the data must only be conducted if first authorized by a judge. The president, who has been criticized for allowing the NSA to collect almost 200 million text messages from across the globe, will announce the proposals at a planned address on government surveillance to be held this Friday. He is also expected to pledge extended privacy protections to non-US citizens and to continuously evaluate sensitive surveillance, particularly involving foreign leaders. He will call on Congress to help determine the NSA program's future.

Back in December, the Review Group on Intelligence and Communication technologies, set up by the president in the wake of NSA data collection revelations by whistleblower Edward Snowden, set out 46 recommendations for improving how intelligence services accessed data. These included the recommendation that a "higher authority" grant the collection of data from now on — hence Obama's announcement of the judicial authorization. It also included recommendations to limit the collection of foreign data (although Obama's claimed very little of it is collected in the first place), and to ensure that encryption and private security software remain untouched. (It was previously revealed that the NSA, with its role in developing encryption technology, had actively sought to make encryption standards weaker.)

President Obama is also expected to amend how national security letters work. Designed to obtain business data, Obama now plans to allow recipients to disclose the receipt of the letter after five years, instead of the current lifetime secrecy condition. He is also expected to announce an impartial, non-government privacy advocate to argue before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. Currently, only government officials present at the court.

The reforms sound sensible. But the main question now is — if the NSA won't store data from now on, who will hold it instead — and where? Telecommunications companies and the NSA itself say relocation will be technically difficult. Meanwhile, many privacy advocates don't think changing the location of the data will actually do much to enhance privacy anyway. If the data is still collected, then it's still open to being leaked. Besides, if the government can still mostly gain access if it really wants, what will the proposals really achieve apart from a slowing down of the process of data capture?

Obama is also expected to use his State of the Union address on January 28 to reassure Americans of the proportionality of his plans to balance security needs with surveillance. But it's clear that it's going to take more than choice words to raise faith in technological privacy.