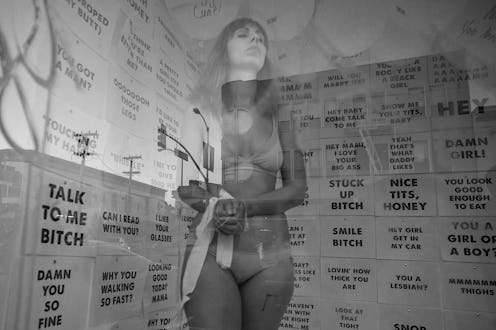

In a culture where people often consider catcalling a compliment, something the victim asks for, or merely an inconvenient side effect of being a woman, artist Mirabelle Jones's "To Skin a Catcaller" installation and performance shows how serious the problem really is. Jones polled people about what street harassers have said to them, and after receiving over 100 responses over social media in a week, she attached print-outs of the words to the walls of a 6-foot by 7-foot room with a street-facing window in San Francisco's ATA Gallery, and played recordings of herself reading them over a loudspeaker while passerby watched her pace for eight hours. Throughout the performance on Nov. 14, her clothes were removed, her hands were bound, and balloons with catcalls scrawled on them and razors dangling from them filled the room to represent the growing sense of restriction and danger victims of street harassment feel.

"It was important to move continuously in the space because street harassment is a kind of interception," Jones told Bustle over email. "It interrupts someone moving from point A to point B and in doing so suggests that whatever they are doing is not as important as how they physically appear as a sex object."

As the Community Arts Organizer for Hollaback! LA and a California Certified Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Advocate, Jones is not only an artist but also an expert on street harassment. She spoke with Bustle via email about what exactly street harassment is and how to best combat it. Here are some of the most important points she made.

The Problem

"There is something very wrong in a society that views an issue that affects 90 percent of women as a 'personal problem,'" Jones said. "Every time there is a piece about street harassment in the media, I have at least a few friends who are amazed to hear that they are not alone in their experiences, that there is actually a way to describe what is happening to them (street harassment), and that it is happening to the majority of society."

Jones clarified that street harassment and sexual harassment are overlapping but distinct categories. While street harassment often includes sexual comments, she said, it "may also include racism and homophobia." Her own survey respondents reported catcalls that "addressed their race, gender presentation, or sexuality in a belittling way," such as "Hey Chinese Girl," "You got a booty like a black girl," "Are you a girl or a boy?" and "Hey lesbians, want to fuck?" While street harassment primarily affects women, she said, "queers, non-binary folk, folks who are intersex, and people of color are also catcalled regardless of whether they identify as women."

The effects of street harassment can be insidious. People alter behaviors they shouldn't have to change just to minimize unwanted attention. Jones said many of the people she polled "go to extreme measures every day to avoid catcalling, such as choosing routes which add significant time to their commute or wearing baggy/unflattering clothes, sunglasses, headphones, or in general covering up." Another effect of street harassment, she said, is distrust in groups that typically commit it. By harassing people based on their gender, race, sexual orientation, or gender identity, street harassers divide us as a society.

The Solution

While it may be tempting to say "If it bothers you so much, why don't you just report it?", reporting often does little but subject victims to shaming and victim-blaming. Jones explains:

If it is helpful to the victim, of course I would encourage them to report. But victims of street harassment sometimes come from communities where their relationship with the police is not always one of trust. That can be due to racism, homophobia, sexism, classism, and a variety of other factors... Many policemen and women, like a huge portion of society, probably don't think street harassment is a serious issue. I have heard of several attempts to report... ignored by the police.

Instead, Jones proposes three possible solutions. One is to create more outlets for people to share their experiences so that people gain "an accurate assessment of what catcalling and street harassment look like in 2015." The Hollaback! app and website, for example, let people write down what has happened to them and let others click "I've got your back" to show support, which validates victims' reactions and provides an alternative to the double-bind in which "if the target responds, they open themselves up to further harassment or even escalation" but "not responding leaves the target with a lack of agency." Hollaback! also maps incidents so people how what is happening in different cities.

Another solution, Jones said, is "more organizations geared towards teaching young men to respect women." Unfortunately, there is currently less funding for preventative measures against rape culture than for resources for victims. Jones proposes:

If we want to see rape culture evaporate (and I very much do), we need to start addressing it where it begins. But it's also hard to do that when you can't even talk about sex in schools, let alone consent. The burden therefore has to fall on organizations hopefully led by men who want to see their young men grow up to be respectful individuals. I say these organizations should be led by men because misogynists by nature will not listen to women. Because rape culture shapes our ideas about sexuality when we're pretty young, young men already tend to have more respect for older men than women by the time they're in their teens. Young men need positive male role models who can show them (contrary to what the media tells them) that respecting women is important.

The third solution is to support one another in public places. "We've got this bubble mentality that says in public spaces we ought to close ourselves off to stay safe, but in doing so, we fail to support each other," Jones said. Intervention doesn't have to mean addressing a catcaller, which can be dangerous, she added, but "a simple, 'Hey, are you all right?' can be truly comforting and might detour further harassment. If they seem comfortable with it, you could even offer to sit with [the victim] or keep them company to detour the harasser."

The Takeaways

Through her performance, Jones hopes to show that "our problem with street harassment is not a personal issue. It's a societal issue and we have a duty to address it as a society," which means doing away with victim-blaming and attacking the root cause: "Street harassment is a symptom of a misogynistic society that promotes rape culture." We also must remember, she said, that this epidemic affects everyone:

We need to see drastic changes in the way so-called "women's issues" are valued in society. Street harassment is not a women's issue. Nor is rape culture. These are issues which affect all of us... Street harassment can lead to changes in the way we interact with each other. For women, this may include our willingness to interact with men, especially strangers. For people of color, this may include our willingness to interact with white people, especially strangers. For queers, this may include our willingness to interact with straight people, especially strangers. It's not fair to blame victims of street harassment for putting up these barriers on account of prolonged or pervasive street harassment. It makes sense to do so if that's what we feel we have to do to stay safe. The problem is not the same as the symptom. The symptom is a distrust of men by women in society. The problem is misogyny and rape culture.

Images: Lieven Leroy/Subversive Photography courtesy of Mirabelle Jones (3); Tim Guydish courtesy of Mirabelle Jones (2)