Brace yourself, ladies, because I'm about to deliver some hard truth. Are you ready? Here it comes: You do not know what you like. You do not know what is good or enjoyable. In fact, many of the things you think are smart are actually dull. And the things you think are fun? Well, those are just boring. It's OK. Don't feel bad. You were just too silly to know the difference. Silly, silly woman.

Most women I know have experienced mansplaining, but now there's a new variety of the irksome trend lurking in the water. Author Jennifer Weiner calls it "Goldfinching," and defines it as the collective actions taken by book critics to devalue those runaway literary bestsellers that are written and read, largely, by women.

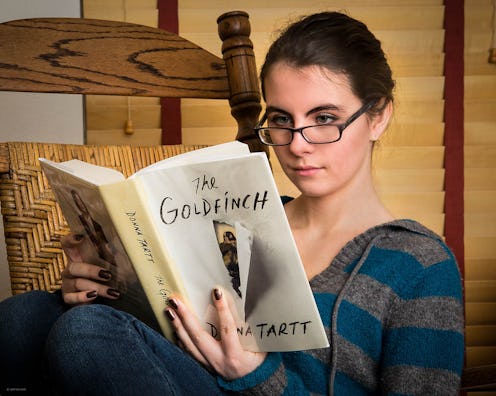

The trope-namer here is Donna Tartt's 2013 novel, The Goldfinch. This bildungsroman follows Theo Decker, an orphaned teen who lives in New York City. A 1654 painting by Carel Fabritius lies at the heart of the novel, and young Theo comes to be its protector after a terrible event claims the life of his single mother.

The Goldfinch spent more than 40 weeks as a New York Times bestseller, and drew heaping praise. New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani applauded the author, saying:

Ms. Tartt is adept at harnessing all the conventions of the Dickensian novel — including startling coincidences and sudden swerves of fortune — to lend Theo’s story a stark, folk-tale dimension as well as a visceral appreciation of the randomness of life and fate’s sometimes cruel sense of humor.

But accolades from a Pulitzer Prize-winning critic did not prevent The Goldfinch from, well, getting Goldfinched. Detractors harped on the whimsy of Tartt's novel, with critics at both The New Yorker and London Review of Books likening it to a children's story. After The Goldfinch won its own Pultizer — for fiction, in 2014 — New Yorker critic James Wood told Vanity Fair: "I think that the rapture with which this novel has been received is further proof of the infantilization of our literary culture: a world in which adults go around reading Harry Potter."

Weiner lays out the key elements of Goldfinching as such:

- the author's writing will be called "sloppy or sentimental";

- critics' dismissals will come "in specifically gendered terms," with "female coded plot twists or character traits ... held up for particular mockery";

- and, of course, "Goldfinching must include considerable smirking about the immaturity and childishness of the book, its author ... and its readers."

Gone Girl and A Little Life are among the other notable novels to receive a good Goldfinching from critics. Writing about the latter in The New York Review of Books , Daniel Mendelsohn claimed that "the guilty pleasures it holds for some readers are those of a teenaged rap session." It is women's collective longing to re-experience teen angst, at least according to Mendelsohn, that earned Hanya Yanagihara's novel its Man Booker nod. Uh-huh.

Just like mansplaining and the idea that women need help to find music, Goldfinching stems from pure misogyny. For authors who write "like women," and those whose work appeals to women, it's a process by which critics can devalue their success. Even when that success results in winning the highest literary prizes in the land, the Goldfinchers maintain that writers like Tartt and Yanagihara "certainly haven’t written literature."

For readers, it's worse. To enjoy a Goldfinched book is to contribute to the downfall of the literary institution. Us silly women are the reason A Little Life made the Booker Prize shortlist when Jonathan Franzen's Purity didn't get so much as a longlist nod. We're powerful. And they don't like it.