If you ask feminists if they want their movement to be exclusively for white, upper-class, able-bodied, cis, straight women, the great majority would say "no." But if you don't regularly have to deal with issues faced by certain groups, you may not automatically know how to be an intersectional feminist. It's hard to understand what difficulties people are facing when we don't experience or witness them ourselves. Fortunately, though, there's a lot of information out there right now from people who have been marginalized within the feminist movement on how to not exclude them.

Many of the reasons feminism needs to be intersectional are the same reasons we need feminism in the first place: Because certain perspectives are underrepresented and dismissed in our society, because we don't always recognize the ways people are oppressed and therefore need to listen closely to the oppressed groups themselves, and because no demographic is more valuable than any other. Failing to be intersectional goes against the very tenets of feminism. Yet we do it all the time without even knowing it.

Here are some ways that all feminists can make intersectionality a bigger part of our mission:

1. Use Your Platform To Advocate For Those Who Don't Have One

While Emma Watson's response when asked if she was a "white feminist" (i.e. a feminist who ignores the concerns of non-white women) may have been a bit defensive, she has still used her privilege to draw attention to issues of those who do not enjoy the same privilege: She has traveled to Uruguay and other places as a UN ambassador to hear the top concerns of women in those countries. Obviously, not all of us can travel the world, but we can talk to or read about people whose identities are different from ours and bring up their perspectives in future discussions of feminism. Those in privileged positions due to gender, race, or anything else would do well to use that privilege to help others who may less often be heard gain the platform they need.

2. Listen To Underprivileged Groups, Even When They're Criticizing Your Own Group

Recently, someone shared an article in a feminist Facebook group on problematic things white feminists say to black feminists. One member (a white woman) said the author was being "divisive" for criticizing other feminists and undermining our solidarity. In reality, though, it's racism that undermines feminist solidarity, and articles like that one are helpful in rectifying this so that feminism can be less divisive. When we don't listen to people who are trying to tell us how to improve our movement, we preserve all the problems that weaken the movement overall. And if your impulse is to disagree with someone about an experience specific to their identity, remember that you don't know what it's like to be them. If you're a woman, think about what it's like when men deny your experiences of sexism. That's what it's like when privileged feminists undermine the criticisms and stories of marginalized women.

3. Be Conscious Of Your Pronouns And Other Gendered Language

People, feminists included, often discuss feminist issues using gendered assumptions. For example, people too often talk about sexual assault as something men commit against women, or of romantic relationships as if they are always between men and women. Feminists also sometimes say things like "people lucky enough to be born with a penis" to refer to male privilege (when actually male privilege exclusively affects those who identify as men), "women need access to contraceptives" (when everyone capable of getting pregnant does, regardless of their gender identity), and "there is no women's sexuality without the clit" (yes, there is, because many women don't have clits). As always, don't assume the gender or sex of any real or hypothetical person.

4. Examine Your Use Of Metaphors

Many of the most common metaphors used by feminists contain hints of ableism. For example, saying that women have been "crippled" or "handicapped" uses disabilities as symbols of holding a lower status. Other feminist cultural critiques use terms offensive to sex workers; for example, criticizing marriage as "a form of prostitution" implies that all sex workers are oppressed, and calling degrading imagery of women "pornographic" devalues those who choose to work in the porn industry.

5. Make Your Body Positivity Fat-Positive

Too often, I see thin or average-sized women doing body positivity wrong — so wrong that the fat-positive movement arose because the body-positive movement was excluding fat people. We do this every time we say "You're not fat! You're beautiful!", or share supposedly body-positive campaigns that only include thin women, or say "men like curves", or do anything else that predicates a woman's ability to eat and weigh what she wants on her ability to appeal to the male gaze. Also be careful with the way you talk about your own body. It's okay to admit to having insecurities, but complaining about what size you are or how many calories you ate can encourage the idea that your size or food consumption are bad, which might have especially offensive implications for other people. Keep your complaints about the destructive messages you've heard about size, not your size itself.

6. Seek Out Diverse Opinions

Recently, I witnessed an illustration of why it's so important to get diverse perspectives on feminist issues. After I wrote an article on "nice guy syndrome," a reader pointed out that, by including the name of someone who committed a violent crime to punish women for rejecting "nice guys," I gave him what he wanted by memorializing him and also risked triggering people who witnessed the crime. My initial reaction was that it should probably be removed, but an editor who happened to be a black woman brought up an excellent point I didn't think of: Leaving in the name of a white man could help dispel stereotypes about race and crime. I would not have thought about this as a white person. We ultimately removed it, but it sparked a necessary discussion. This is one of many instances when soliciting diverse opinions exposes our blind spots and helps us do feminism better.

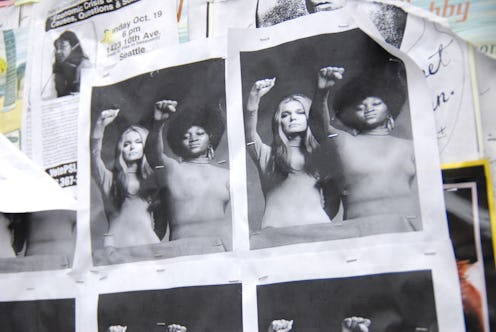

Images: Jonathan McIntosh/Flickr