News

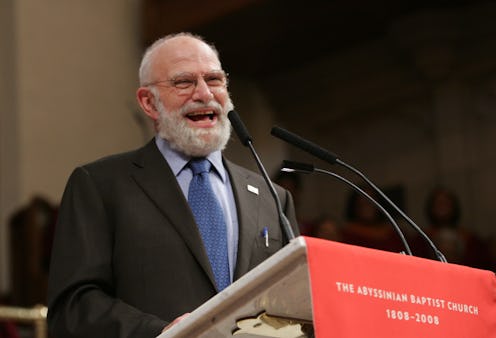

Quirky Neurologist Oliver Sacks Has Died

Well-known neurologist and author Oliver Sacks died of cancer Sunday, according to USA Today. One of Sacks' most popular books was The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, which explored how some of his patients dealt with conditions such as autism, Tourette's syndrome, and Parkinson's disease. In 1990, Sacks' 1973 memoir, Awakenings, was turned into a film featuring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro, according to NPR. He also taught at the NYU School of Medicine and Columbia University Medical Center.

Unlike many scientists or medical doctors, Sacks achieved notoriety both in the medical field and in creative fields. His books are still popular, even to people who don't have a background in psychiatry or neurology, because of the ways in which Sacks portrayed his patients. Some of his books were turned into films and adapted for the stage.Author Lisa Appignanesi wrote in The Guardian that Sacks told his patients' stories as if they were characters.

"No mere objects of hasty clinical notes, or articles in professional journals, his 'patients' are transformed by his interest, sympathetic gaze and ability to convey optimism in tragedy into grand characters who can transcend their conditions," Appignanesi wrote. "They emerge as the very types of our neuroscientific age."

Sacks has described his books and essays as case histories, pathographies, clinical tales, or "neurological novels," according to The New York Times. Some of his subjects included, "Madeleine J., a blind woman who perceived her hands only as useless 'lumps of dough'; Jimmie G., a submarine radio operator whose amnesia stranded him for more than three decades in 1945; and Dr. P. — the man who mistook his wife for a hat — whose brain lost the ability to decipher what his eyes were seeing," according to the Times. Sacks was one of the first neurologists to introduce Tourette's syndrome and Asperger's to a general audience by humanizing the conditions through his novels.

“I love to discover potential in people who aren't thought to have any," he told People magazine in 1986.

Not everyone was a fan of Sacks' dramatized, storytelling style, though. Disability-rights activist Tom Shakespeare accused Sacks of exploiting the people he wrote about. Shakespeare called Sacks "the man who mistook his patients for a literary career," according to the Times.

Despite these criticisms, most people knew Sacks as a quirky, insightful, and inspiring man. During his residency at the University of California, Los Angeles, he entered weight-lifting competitions and joined the Hells Angels on motorcycle trips to the Grand Canyon — adventures he detailed in his 2015 memoir, On the Move: A Life, according to the Times. In the same book, he described the moment during his adolescence when he realized he was gay. He described several of his flings, then said he became celibate for 35 years until he found his partner of eight years, writer Bill Hayes.

Sacks' quirkiness carried over into every aspect of his life. He credited his later studies of hallucinations to his experimentation with LSD while he was younger, according to NPR. He also received about 10,000 letters a year and told the Times, "I invariably reply to people under 10, over 90, or in prison."

He began his career as a researcher, but he said he didn't have the hand-eye coordination or the temperament for lab work. He hilariously characterized his move to clinical work in a 2005 interview, according to the Times:

I lost samples, I broke machines. Finally they said to me: "Sacks, you're a menace. Get out. Go see patients. They matter less."

Sacks, who played the piano well, also wrote a book called Musicophilia, which explored the relationship between music and the mind. Sacks believed that music appreciation is hard-wired into the brain, pointing to evidence that music can reach dementia patients, according to the Times. Sacks once referred to Friedrich Nietzsche’s claim that listening to composer Georges Bizet made him a better philosopher, saying that he thought Mozart made him a better neurologist.

In a 1989 interview for The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, Sacks described how he would like to be remembered in 100 years, according to the Times:

I would like it to be thought that I had listened carefully to what patients and others have told me, that I’ve tried to imagine what it was like for them, and that I tried to convey this. And, to use a biblical term, bore witness.

In an opinion piece for the Times earlier this month, Sacks described his worsening cancer and said he planned to live out his remaining months in the "richest, deepest, most productive way" he could, according to NPR:

[N]ow, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual, but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life — achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one's life as well, when one can feel that one's work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest.