News

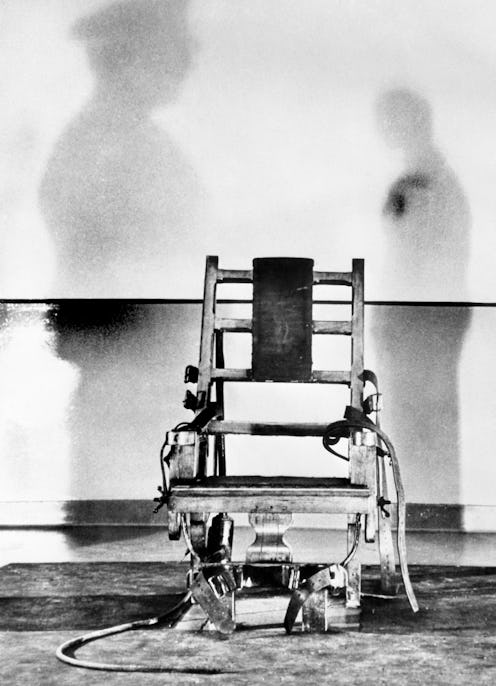

The Racial Inequality Of The Death Penalty

Since capital punishment was reinstated in the United States in 1976, the death penalty has treated black and white murderers differently, and the racial discrepancies regarding the death penalty are astronomic, both in number and in public opinion. Dylann Roof, the white supremacist who allegedly murdered nine African Americans in June inside a Charleston, South Carolina, church, is likely on his way to a death penalty conviction. But he'll be joining a small club since white-on-black killers are, in fact, rarely put on death row.

At first glance, there doesn't appear to be much racial disparity among death penalty recipients. The Death Penalty Information Center states 784 white individuals have been executed since 1976 compared to 490 African Americans. Black inmates and white inmates are more or less equally represented on death row as well (41 percent and 42 percent, respectively). But the numbers get concerning when you take into account that, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, African Americans make up 13 percent of the population. And even more concerning are the differences in the race of the victims.

In all cases resulting in execution in the last 40 years, 75 percent of the victims were white, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Black people represent 15 percent of victims in death penalty cases, even though they are eight times more likely to be a homicide victim than white individuals, according to FiveThirtyEight's estimates.

If Roof is sentenced to death, he would become the 32nd Caucasian to be executed for killing a black victim since 1976. Compare that to 294 black individuals who have been executed for killing a white victim, according Death Penalty Information Center's numbers. This means that blacks are executed nine times more for interracial murders than white people. But the corresponding amount of black-on-white crime doesn't remotely match this number. A 2013 FBI report states that 7 percent of black homicide victims are killed by Caucasians, while 14 percent of white victims are killed by African Americans. That means black-on-white murders are twice as likely as white-on-black ones. So how come African Americans are executed so much more frequently?

Part of the discrepancies in interracial murder death sentences could have something to do with public opinion. When pushing for the death penalty, prosecutors do consider the wishes of the victim's family, and only 36 percent of black Americans support the death penalty. But it's unlikely that this alone explains the lack of white executions. In cases where there is a black victim, such as with the Roof case, the black community is far more likely to speak out against the death penalty, and offer forgiveness to the killer. But this is a cultural difference, likely tied to the black community's long and unjust relationship with the death penalty.

Although the earliest American settlers brought over English laws and penalties, Slate cites author Stuart Banner in pointing out that the first American-made capital punishment was put into effect directly after a slave revolt in 1712. In early America, slaves could be sentenced to death for the most minutia of crimes, in addition to murder or rape. By the mid-1800s, though most states had reserved the death penalty only for murder, Slate claims Louisiana and a handful of other states still enforced it for any action that could cause riots among slaves or free blacks.

Fear of legal execution was a psychological weapon wielded over slaves and the black community for decades and decades so it should come as no surprise that African Americans dislike the death penalty so strongly, even to the point of trying to spare white murderers from it. But when a race that makes up 13 percent of the population accounts for half of the country's executions, it's difficult to imagine that the decades of fear and racial inequality are actually behind us.

Images: Getty Images (2)