News

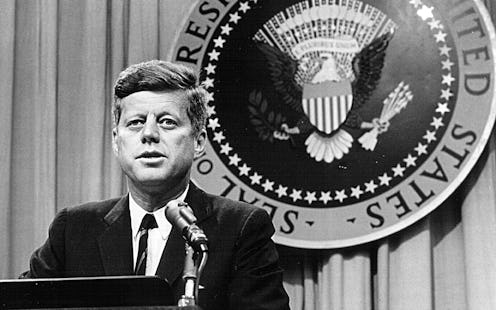

Was John F. Kennedy Good For Women?

On Friday, the nation marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of former President John F. Kennedy. Kennedy, of course, is generally remembered as one of America's finest presidents. But less clear is the legacy of this question: was he good for women? Any honest discussion about John Kennedy’s gender politics has to recognize the fact that, in his personal life, Kennedy was a scumbag. There's just isn't really any way around that, and this goes beyond his general womanizing and philandering.

Consider, for example, the account of Mimi Alford, who alleges to have had an extended affair with Kennedy when she was a 19-year-old White House intern. After a few flirtatious encounters, President Kennedy took Alford to Jacqueline Kennedy’s bedroom and basically shoved her onto his wife’s bed:

He placed both hands on my shoulders and guided me toward the edge of the bed. I landed on my elbows, frozen halfway between sitting up and lying on my back.

That’s when Alford lost her virginity, and the two embarked on an 18-month affair, according to Alford. Kennedy also offered her drugs (she didn't say what kind), and she claims to have been in Kennedy's bed when he was downstairs dealing with the Cuban Missile Crisis. But things turned sour when Kennedy started instructing her to perform oral sex on his aides (“Mr. Powers looks a little tense — would you take care of it?”) and family members (“Mimi, why don’t you take care of my baby brother — he could stand a little relaxation”) — all while the president watched. And that’s apparently when the affair ended, as Alford drew the line at servicing Ted Kennedy.

JFK, then, was a card-carrying douchebag, at least as far as his personal life goes. His misogynistic conduct caused direct harm to many of the women with whom he surrounded himself — in her book, Alford talks about the years of psychological damage she had to work through after the affair — and that’s a significant, unavoidable aspect of “John F. Kennedy’s effect on women,” to put it broadly.

But because he was also President of the United States, Kennedy had the power to impact women in different, exponentially more more far-reaching ways than simply through his personal interactions with them. For example, he could have proposed legislation and set federal policy to advance women’s opportunity.

Did he? Did he direct his administration to devote substantial time finding ways to improve women’s equality in America? Did he, simply by addressing these issues publicly, force the country as a whole to truly think about the importance of gender equality? To truly assess Kennedy’s record with women, these questions are just as important as his extramarital dalliances and general misogyny.

The personal values of U.S. presidents — particularly with regard to oppressed minorities — often collide with their official actions as president. For example, Richard Nixon was unabashedly anti-Semitic (“Most Jews are disloyal...you can’t trust the bastards,” he once said). However, he nevertheless gave Jews enormous influence in his cabinet — in the 70s and arguably earlier, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was essentially Nixon’s co-president, and he appointed plenty of other Jews to positions of high power as well. When it came to extramarital affairs, Bill Clinton followed dutifully in JFK’s footsteps, and according to some reports, he still does. But he also expanded abortion access on an unprecedented level, signed the Violence Against Women Act into law, and enacted a whole bunch of other pro-woman policies.

The fact of the matter is that President Kennedy was something of a feminist president. Despite his sleazy conduct as a husband, he did a whole lot of good things for the nation’s women on the whole, both directly and indirectly. The most obvious example of this is his establishment, in December 1961, of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women.

Kennedy announced this as the country was debating the Equal Rights Amendment, a proposed constitutional amendment that would have sought to rectify workplace inequalities for women. It had been first introduced in Congress 1920 but was never ratified, and there was substantial disagreement, even within women’s groups, as to whether the ERA as written would have actually benefit women. Kennedy formed the commission not to address the ERA directly, but rather to answer that broader question: What would be the best way for the government to make America a more fair place for both genders?

As he put it in the speech announcing the commission:

We naturally deplore those economic conditions which require women to work unless they desire to do so, and the programs of our Administration are designed to improve family incomes so that women can make their own decisions in this area. Women should not be considered a marginal group to be employed periodically only to be denied opportunity to satisfy their needs and aspirations when unemployment rises or a war ends.

Women have basic rights which should be respected and fostered as part of our Nation's commitment to human dignity, freedom, and democracy.

There are traces of 1950s-era gender normativity in this announcement: Kennedy’s proclamation that “women have brought into public affairs great sensitivity to human need and opposition to selfish and corrupt purposes” reeks of gender stereotyping, even though it’s obviously well-intentioned. But the task force itself was a big, generally progressive deal. Kennedy appointed Eleanor Roosevelt to chair it, and gave it just under two years to develop “recommendations for overcoming discriminations in government and private employment on the basis of sex.”

In October 1963, just a month before Kennedy’s death, the commission presented its report. It wasn’t just a stack of papers relegated to some obscure government building: The Associated Press turned it into a four-part TV series, and it was later printed and sold as a book. The report recommended, amongst other things, paid maternity leave for women workers, an end to gender discrimination in hiring practices, equal pay for women, and universal child care (!). It also called on the Supreme Court to recognize women as men’s equals under the Fourteenth Amendment.

While the commission’s advice was non-binding, Kennedy began acting in the spirit of its recommendations even before the report was complete. In 1962, at the request of the panel, he ordered all federal agencies to ban gender discrimination in hiring. The next year, he signed the Equal Pay Act, which mandated equal wages for men and women in the federal workplace, and while that legislation didn’t touch the private sector, it paved the way for future legislation to do so, and itself a significant step toward rectifying the wage gap.

The commission had several indirect effects on women’s equality as well. State commissions started sprouting up shortly after Kennedy announced the federal version; this was one recommendation of the commission itself. Those state commissions eventually merged into the Interstate Association of Commissions for Women, which later became the National Association of Commissions for Women. That’s not the only prominent women’s group with roots in Kennedy’s commission: Dr. Pauli Murray, one of the commission’s original 20 members, later went on to co-found the National Organization for Women.

The final report wasn't perfect. According to Harvard lecturer Elizabeth S. More, who wrote a paper on the topic, it was “characterized by internal tension between treating women primarily as homemakers and presenting them as equal participants in the public and economic realms.” While it encourages women to think beyond “stubbornly persistent expectations about ‘women’s roles,’” it nevertheless also recommends that girls — and not boys — learn “home management” at an early age. On the whole, though, it’s difficult to argue that the commission, on the aggregate, was anything other than good for women.

In some ways, Kennedy’s record with women is reminiscent of disgraced former San Diego Mayor Bob Filner. While Filner had an admirable legislative career, he was accused of sexual harassment by no fewer than 18 women. As with Filner (and Nixon, and Clinton), it’s difficult to square Kennedy’s actions as a private citizen with his actions as president. If he cared so much about women, why did he treat them like dirt? And if he didn’t care about them, why did he do so much to help them?

Perhaps the biggest lesson here is that questions like “was Kennedy good for women?” are misleadingly simplistic. They unintentionally conflate the personal with the professional, and require more than one word to answer (more like 1,400 words, at current count). Kennedy was good for the women of the nation, bad for the women in his immediate vicinity, and that’s probably about as close to an answer as we’re ever going to get.