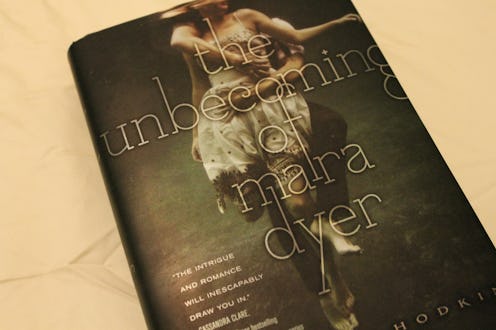

Books

I'm A YA Best Seller, But I Never Wanted To Write

I never wanted to be a novelist. I didn’t sit around in third grade writing short stories with crayons. I didn’t spend junior high writing fan fiction about the characters from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I didn’t spend my college years publishing sensitive, delicately crafted Raymond Carver-esque short stories in my college literary magazine. I never got an MFA. I was a lawyer without a literary bone in my body when my novel happened to me.

I feel like a jerk writing this. A lucky jerk. My path to publication was, outwardly, a success story: 10 months from first words to first agent, a year and 10 days from first words to first sale. But it didn’t actually start with those first words. It began, as many YA novels do, in high school, where I spent most of my afternoons theater-geeking or drawing Lord of the Rings fan art. I had frizzy hair and pale skin and freckles I hated. Guess how popular I was? No, really, guess.

The bullying was insidious, and it wasn’t just other kids, either. One teacher was so awful that, when the principal and administration were informed about the issue and did nothing, I decided to leave high school a year early. I felt so powerless then, so trapped — stuck going to the same place, day after day, with people who couldn’t stand me whom I couldn’t stand. But before I escaped high school, I escaped in books. I read anything and everything and wanted to keep doing that, so I chose English as a major and professor as a career. But an experience at an animal shelter during my junior year of college derailed everything.

I was volunteering as a kennel tech when 42 animals were seized in a cruelty case. All of them were starving, many of them were sick, and they needed the help of every staff member and volunteer just to survive. Over the course of the summer, and the rest of that year, the case made its way through the legal system but ultimately, even though the man who abused them was punished, he wasn’t punished much. Animals are property in America (even though corporations are people), and the laws to protect them are inadequate at best. I wanted to change that, so I went to law school thinking I could.

So why did I become I writer? Because I needed to.

Spoiler alert: I couldn’t. There weren’t many jobs in animal law at the time, but before graduation I was offered an associate position at a law firm doing anti-terrorism litigation. If I couldn’t help animals, helping people seemed like a good consolation prize, so I said yes.

I was there for a year before I bought a house with a picket fence and a tree swing and oak trees that dotted the yard. An SUV to someday, maybe, pack with children. I had my sh*t together — a career, a car, a house, a life — at 24, 25, 26, 27 —what more could I possibly want?

A lot more, as it turned out.

I was performing without realizing it, the central character in a narrative where sharp, capable Jewish girl goes out and becomes something, despite the mean girls who made her feel like nothing. I inhabited that character well, and it was 2009 — 10 years post high school — before I was ready to admit that the life I’d painstakingly built, the impressive life, the perfect-on-paper life, wasn’t the life I wanted.

Everyone always wants to know the “what” in the equation: What inspired you to write your novel? But I think that’s the wrong question. Life inspires novels — conversations, memories, observations, jokes—but they don’t always result in books. The question isn’t what inspired me to write — it’s why.

Life inspires novels — conversations, memories, observations, jokes — but they don’t always result in books. The question isn’t what inspired me to write — it’s why.

Like every other novelist, my book was inspired by an idea. I’ve had lots of those, and it’s hard to articulate what it was about this one that held me hostage. All I knew was that the protagonist would be named Mara Dyer, and that something was happening to her. A transformation, an evolution — she would become something other than the powerless teenage girl she was when the novel began.

It didn’t matter that I’d never filled a journal with angsty teen poetry or thinly veiled autobiographical stories. It didn’t matter that I hadn’t taken a single creative writing class in college. I remember, in lurid, excruciating detail, what it felt like to be a teenager, and as it turns out, that’s all I needed.

The first night, I wrote 5,000 words. The next week, I had 20,000 words. I had something to say, something I’d been needing to say since I was a teenager, but couldn’t articulate then. And the more I wrote, the more I realized that bits of my other life, my real and supposedly perfect life, were falling away. And I didn’t miss them.

So why did I become I writer? Because I needed to. I just had to be someone else first.

Image: Ashley Van Der Kley/flickr; Simon & Schuster