Books

We Should All Talk About 'All the Bright Places'

"People rarely bring flowers to a suicide," author Jennifer Niven says in the afterward to her debut YA novel All the Bright Places (Knopf Books for Young Readers). And Niven's treatment of the stigma around mental health and suicide is what rises her novel from the ranks of other teenage love stories. All the Bright Places is the kind of book that anyone struggling with depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, or any mental health concerns ― or anyone who is close to someone who is ― needs to read and absorb into her being. Oh, and that essentially means everyone.

High schoolers Violet Markey and Theodore Finch meet atop the school bell tower, where both have them have gone to contemplate suicide by jumping. And that's the beginning of the story. The two find their way down, and they end up pairing up for a school project sending them to explore the natural wonders of their state. As the two "wander" together, they open up to each other about their pasts, their obsessions with death and suicide, and their families, but just because life seems wonderful now, it doesn't mean that those dark feelings can truly go away.

Mental health and suicide are issues close to Niven's heart. As she says in the book, every 40 seconds someone in the world commits suicide. The author's great-grandfather himself died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. And several years before she wrote All The Bright Places , Niven was the one to discover a friend who had killed himself.

This closeness to the issue clearly fuels Niven's passion for exploring the subject, and that passion has developed into her excellent, precise writing and the honesty of Finch and Violet. She strikes right in the heart of what it's like living with mental illness in contemporary America. With that, she slams the door on the swirling misinformation and misunderstandings that surround it through her memorable characters.

In particular, there are five ways her exploration of mental health is unlike so many other books out there, and why it's so important.

Niven Weaves in Real-Life Voices of Those Who Have Committed Suicide

Virginia Woolf ― who history says suffered from bipolar disorder and who committed suicide by drowning ― plays a major role in bringing Violet and Finch together. They quote passages from her work The Waves back and forth across social media as they are getting to know each other.

Finch also becomes hooked on the words and lives of 1950s-era poet Cesare Pavese committed suicide with sleeping pills and Vladimir Mayakovski, a Russian Revolution poet who shot himself at age 36:

My beloved boatis broken on the rocks of daily life.I've paid my debtsand no longer need to countpains I've suffered at the hands of others.The misfortunesand the insults.Good luck to those who remain.

Though we're reading fiction, the issues it tackles and the voices within the pages are very, very real.

She Knows, As Do Her Characters, That Outsiders Just Don't Understand

Though in different ways, neither Violet's friends nor Finch's family can really grasp that they're suffering. It's an issue that is so clear in our current society, telling those with anxiety to relax or those with depression to cheer up. Yes, we do seem to be getting better at finding, diagnosing, and treating mental illness, but there's still a lack of understanding about a disease that people can't see, that isn't physical.

At one point in particular, Finch describes this so clearly:

I can go downstairs right now and let my mom know how I'm feeling ― if she's even home ― but she'll tell me to help myself to the Advil in her purse and that I need to relax and stop getting myself worked up, because in this house there's no such thing as being sick unless you can measure it with a thermometer under the tongue. Things fall into categories of black and white ― bad mood, bad temper, loses control, feels sad, feels blue.

And that a Big Piece of Mental Illness Is Feeling Trapped In Yourself

While others are prescribing Advil or telling you to stop being blue, people suffering from depression or another mental illness feel trapped and alone in their own head spaces:

It's hard to describe, but I imagine the way I am at this moment is a lot like getting sucked into a vortex. Everything is dark and churning, but slow churning instead of fast, and this great weight pulling you down, like its attached to your feet even if you can't see it. I think, This is what it must feel like to be trapped in quicksand.

And that leads to fear of your own self:

I'm most afraid of Asleep and impending, weightless doom. I'm most afraid of me.

And this whole process of being mentally ill? It's exhausting. Or as characters (no spoilers!) in the novel describe, it makes "a weary traveler who just needs rest."

There's a Stigma, and Those Suffering Can Feel Its Weight

When one of the characters goes to a support group for those who have attempted suicide, it's not an easy process.

I want to get away from these kids who never did anything to anyone except be born with different brains and different wiring ... I want to get away from the stigma they all clearly feel just because they have an illness of the mind as opposed to, say, an illness of the lungs or blood

According to Niven's own stats from Mental Health America, 2.5 million Americans are known to have bipolar disorder, but the actual number of bipolar sufferers is actually closer to three times that. And on the whole, around 80 percent of mental illness goes either undiagnosed or misdiagnosed.

That's stigma.

And the stigma leads to people not wanting to be labeled with any disorder of the brain. Because, as Finch so eloquently describes, it can be the first step for people to write you off:

Labels like 'bipolar' say This is why you are the way you are. This is who you are. They explain people away as illnesses.

But, Nivens Knows That Suicide Can Consume Anyone Suffering

Part of the writing is taking stock of everything in my life, like I'm running down a checklist: Amazing girlfriend ― check. decent friends ― check. Roof over my head ― check. Food in my mouth ― check. I will never be short and probably not bald, if my dad and grandfathers are any indication. On my good days, I can out think most people. I'm decent on the guitar and I have an okay voice. I can write songs. Ones that will change the world. Everything seems to be in working order, but I go over the list again and again in case I'm forgetting something, making myself think beyond the big things in case there's something hiding out in the smaller details.

Having a "happy" life does not mean someone can't be suicidal. And I want to give Niven a big hug for understanding that and translating it onto her characters. We know this from real life. As Finch describes in the book, the poet Pavese was the height of his career, well respected and loved, when he took his own life.

This Lack of Understanding Makes People Think Suicide Is Selfish

It's not. Nivens knows that, and hopefully any of her readers will see that, too. As one of the members of the support group for those who have attempted suicide says:

"My sister died of leukemia, and you should have seen the flowers and the sympathy." She holds up her wrists, and even across the table I can see the scars. "But when I nearly died, no flowers were sent, no casseroles were baked. I was selfish and crazy for wasting my life when my sister had hers taken away."

It's a sentiment that Violet understands ― particularly after her older sister dies in a car accident. She believes her parents will see suicide as a "wasteful, hateful, stupid thing to do," in light of her sister's accidental death.

But after getting to know Violet and Finch so deeply, hopefully Niven can correct some of these misconceptions and lend empathy to those suffering from mental illness, reach out to both those suffering and friends of those who are who can help. With her vibrant, funny, and heart-wrenching story All the Bright Places, (which, by the way, is set to be an Elle Fanning movie) she can only be advancing the cause. And that in itself deserves attention.

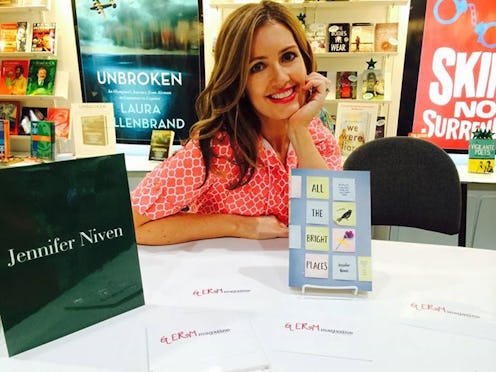

Images: Jennifer Niven/Facebook (2)